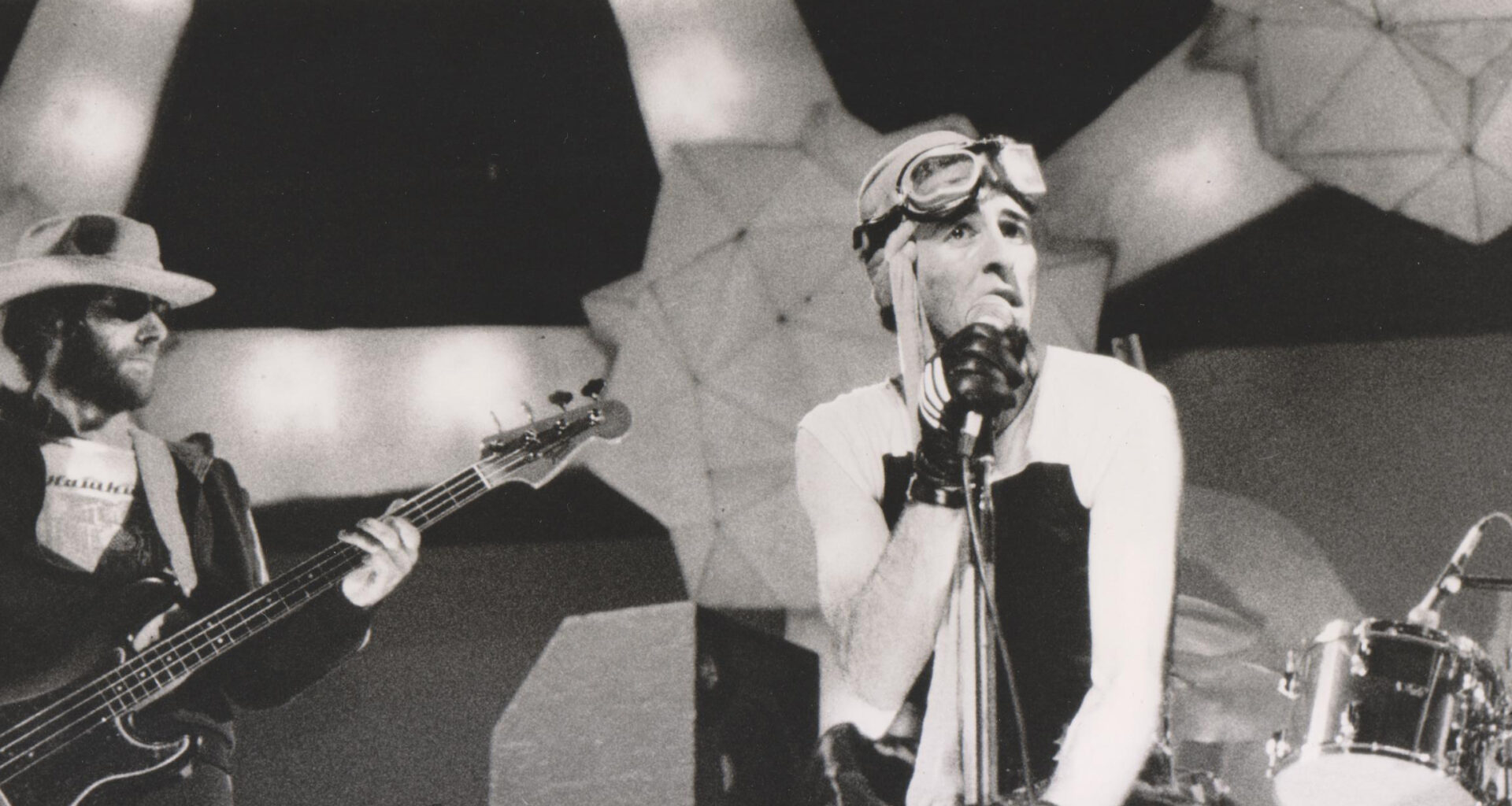

It would seem that the solo output of Hawkwind’s visionary frontman Robert Calvert is something of a best-kept secret. We reveal the untold story of his maverick work as an electronic pioneer

Want to read more?

Sign up to Electronic Sound Premium to gain access to every post, video, special offers, and more. 100%, all you can eat, no commitment, cancel any time.

Already a premium member? Log in here