From her early forays into sound at the San Francisco Tape Music Center and her avant-garde Buchla performances, to leaking electronics into the American consciousness via advertising while earning a string of Grammy nominations, Suzanne Ciani is now one of the world’s most respected electronic music composers. It’s been one hell of a battle to get there, though

The 2018 BBC Proms at the Royal Albert Hall, Prom 13, ‘Pioneers Of Sound’, was an extraordinary night of music. The event was built around the premiere of ‘Still Point’, a piece written for two orchestras and electronic manipulations via turntables. It’s a dazzlingly ambitious work, composed in 1948 by Daphne Oram, then aged just 23, almost 10 years before she was appointed head of the newly created Radiophonic Workshop.

Oram, then a “sound balancer” at the BBC, submitted ‘Still Point’ for consideration as the BBC’s entry for the Prix Italia. Her bosses couldn’t even begin to wrap their heads around what Oram had presented to them. They rejected it and chucked the score into some dusty archive, no doubt hoping it would be eaten by mice. They had no idea what a visionary genius they had under their noses. And while nobody said it out loud, the fact that she was a young woman made it easy for them to disregard her work with such off-handed derision.

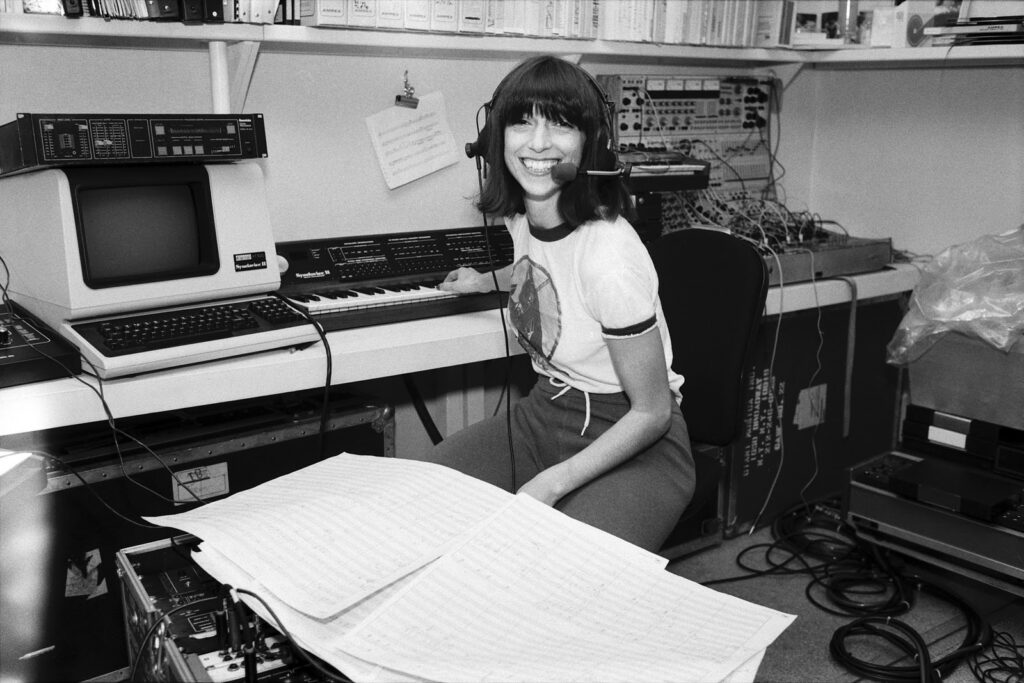

On the same bill that night at the 2018 BBC Proms was Suzanne Ciani. Appearing with her Buchla and an iPad running the Animoog app, she produced a thrilling live improvisation.

“You know, I didn’t know Daphne Oram,” says Ciani, speaking from isolation at her beachfront San Francisco Bay Area studio, where the ocean is so close it almost laps at the windows. “And I should have. It was incredible! Why didn’t I have her as somebody in my history? It’s so important to feel the connectedness of your identity. It’s just massive.”

The performance of Oram’s ’Still Point’ moved her so much, she says, that she cried.

“I cried that I was never allowed to know her and that she was never allowed to actually present that piece. She had two orchestras! Two orchestras side by side, one of them live processed, to enhance the message. I mean, she wrote ’Still Point’ just after the war. It was brilliant, it was revolutionary.”

Daphne Oram was marginalised because she was a woman and Suzanne Ciani can, as they say in California, relate. Twenty years after Oram was sidelined and disregarded by men in fusty post-war London, Ciani was enduring a similar misogyny in hip West Coast America. Plus ça change…

“As a composer, and that’s how I thought of myself, I was getting trained in composition,” she says when discussing her musical training at the University of California, Berkeley, in the late 1960s. “I experienced a lot of…” she sighs and breaks off. “When you’re young like that, you’re very vulnerable and raw and open. And I was invalidated repeatedly. As a woman.”

History repeats, depressingly.

“Women were not really seen as people,” she continues. “Men didn’t know how to relate to us professionally. They could relate to you as an object, like, ‘Nice legs!’ or…”

She starts laughing.

“At my musical department, there were categorical dismissals. I was on a conducting programme, because you had to be able to conduct if you were going to be a symphonic composer, right? And my conducting teacher said, ‘Women have no right on the podium’. And then my composition teacher would say, ‘What’s wrong with women? They can’t compose long pieces!’. I can remember being in the ladies room in the music department one day and I burst into tears. I thought to myself, ‘I need to get out of this dilemma’. I wasn’t accepted.”

Ciani credits these experiences, if credit is the right word here, for pushing her towards electronic music. If the male world of classical composition was going to make it so difficult for her to advance, then perhaps electronics could provide an escape route.

“My theory now, after all my thinking and observing this phenomenon over the arc of time, is that women had an intuitive attraction to electronics because it made them independent. You didn’t have to answer to anybody else. You had the whole thing right there.”

That’s not to say that things suddenly fell into place for Ciani when she first encountered Don Buchla and the electronic music making machine he’d built.

“I mean, Buchla was not easy to deal with either,” she says.

But before we get into that, let’s rewind. Suzanne Ciani was born in 1946 at a military base in Indiana, the daughter of a doctor who had been serving in World War II. Soon after, the family moved to Boston, Massachusetts. The Ciani clan was large, five girls and a boy, and they had a substantial house. It was an all-American middle-class childhood.

“It was wonderful,” says Ciani. “Having a very big house was a blessing, because you could always find a cubbyhole where you could be alone. We had a beautiful piano, a Steinway, which I hogged. I didn’t know until years later that my sister resented that I never let her play! It’s a complicated thing, because in a group that large you have all kinds of dynamics. You know, these two sisters are together, then another two sisters are together… But all in all, it was a very fertile environment, a lot of good energy.”

Ciani would have been around 10 years old when Elvis started having hits and 17 when The Beatles had their first Number One in America. Did those two monoliths of pop culture puncture her world?

“I had two bubbles,” she replies. “Because the music from Elvis and The Beatles was just like air, it was all around and I didn’t even think of it as music. It was like a social thing that happened, whereas the music I studied was classical music. I didn’t think of those being in the same world even. One was my private world and the other was the world that everybody was in. But to this day, I love great pop music. I keep thinking I should make a pop song maybe!

“I had the piano and I had my family. I went to a private college, all women, and that was very conservative. But I still escaped and went into Cambridge [Massachusetts] and listened to Bob Dylan. I had my co-conspirators at college, and we would go and do crazy stuff. And then the next thing that was really liberating was being in California, at Berkeley.”

The private college Ciani attended was Wellesley. Hillary Rodham Clinton was there too, in the year below. While the future FLOTUS was honing her political skills, Ciani was sneaking out and getting a taste of the burgeoning counterculture movement. When she graduated in 1968, she went to Berkeley to study for her master’s degree, landing in the geographical and spiritual epicentre of the hippy movement. The California city was the one-time HQ for leading social activist Jerry Rubin, who had dropped out of university four years earlier, and had a long-established tradition of progressive anti-authoritarian protest.

“That was the time,” smiles Ciani. “It was just after the Summer of Love and it was completely off the charts. Berkeley in the 60s was like being in Paris in the 20s.”

She was already in the right frame of mind to become part of the hippy années folles, having arrived after undertaking that quintessential late 1960s life experience – the American road trip.

“I drove across the country with a girlfriend,” she explains. “We drove from Boston to Berkeley, stopping off in New Orleans. You know, whatever, just to do some exploring. And The Beatles’ ‘Hey Jude’ was breaking across the country. As we drove west, that song would be on the radio all the time. I’d never been so far from home. I didn’t even know what Berkeley was.”

There was a moment she can pinpoint when the counterculture introduced itself to her, marking her transition from diligent middle-class classical music scholar to full-on barefoot hippy.

“I was playing Chopin. I was playing piano in the practice room at Berkeley and a rock comes through the window! So I get up and I look out the window to see swarms of protesters outside. I was thinking, ‘What is going on? What is this?’, and I just joined it. I thought everybody was a hippy then. I mean, I had hair down to my waist, I never wore shoes for three years. We had a co-op and I lived with these people and we tried to live off the land. It was a big alternative.”

You went all the way? You weren’t just a weekend hippy?

“No, no,” she laughs. “We thought it would last forever. But, like The Beatles, it didn’t. I think what happens is that, at a certain point, your financial needs wake you up. And my first financial need was my Buchla.”

There’s probably an interesting dissertation to be written about the desire for musical instruments diverting 60s revolutionaries from their cause and back into the welcoming arms of market capitalism. There can’t have been many, though, for whom that instrument was a Buchla synthesiser. There were fewer still who saw it as a lifeline, having been marginalised from a music education for being a woman.

The Buchla synthesiser was the invention of Berkeley physics major Don Buchla. In 1963, he had been commissioned to create electronic music modules for the San Francisco Tape Music Center, the resource founded by Morton Subotnick and Ramón Sender for the exploration of electronic and tape music. By 1966, these rudimentary voltage-controlled modules had evolved into the Buchla 100 Series.

Don Buchla and Robert Moog, who was based over on the other side of the country in New York, were inventing the voltage-controlled synthesiser between them, although their philosophies were poles apart. While Moog wanted to create instruments that musicians could play with a keyboard, Buchla was interested in non-traditional forms of interface, like touch plates that encouraged wholly different interactions. Buchla’s modules themselves didn’t share Moog’s concepts, opting instead for more complex functions that were unique to Buchla.

And Suzanne Ciani wanted one.

“Yep. Berkeley didn’t have one. None of the schools did. They got a Moog in the spring of the year I graduated, but the head of the music department was terrified of this thing and they wouldn’t even take it out of the box.”

The panicked purchase of a large and expensive synthesiser by an educational establishment, only for it to subsequently languish in a storeroom somewhere, seems to be a common narrative of this era.

“Well, it was because it was threatening!” laughs Ciani. “I knew how to play the Moog and I said, ‘Let me at it!’. But they said, ‘No, no, no! You’re not qualified’. So I never touched it.”

She did, however, play the Moog at the San Francisco Tape Music Center. The facility had started out as an ad hoc affair with one tape machine and some contact microphones stashed in an attic, but by the late 1960s it was a hub for West Coast experimental composers, providing a venue and recording studios for a wider net of influential figures including Pauline Oliveros, Terry Riley, Steve Reich and John Cage. By the time Ciani was visiting the Tape Music Center, it had funding and a permanent home at Mills College in Oakland.

“Some people mistakenly say that I worked there,” she notes. “I didn’t have a job there, but for $5 an hour you could go in and play with what they had. They had a big modular Moog and a Buchla 100, as well as a lot of surplus military gear and other things you could play with. Nobody else was ever there. I basically had the place to myself.”

Ciana completed her master’s degree in 1970 and almost immediately took a job at Buchla & Associates. Working for Don Buchla meant she was learning how the machines she loved were put together. She earned her first Buchla system with a soldering iron.

“Buchla was the Leonardo Da Vinci of synthesiser design,” she declares. “He didn’t care about commercialism. He never wanted to be successful. That wasn’t his goal. He just wanted to do the best possible thing. I was a pianist when I started to work for him, but he proselytised me. He said the biggest danger for electronic music is the keyboard, because people think playing a sound on a keyboard is what it’s all about. He was into all this fancy control voltage, of course.”

And lest you think that Ciani had escaped from the misogynistic atmosphere of the music department at Berkeley into a progressive idyll of electronic music and equality, things didn’t initially go smoothly with Buchla.

“He fired me on day one! I just came back in the next day. I am stubborn.”

She stuck it out at the Buchla factory, helping to build synths for $3 an hour. “When the synthesisers were finished, tested and shipped off, I felt as though I were losing children,” she told the New York Times in 1974.

Ciani was also composing, providing music for theatre companies and art galleries. Her first appearance on vinyl was the 1970 album ‘Voices Of Packaged Souls’, a collaboration with the artist Harold Persico Paris commissioned by a gallery in Belgium in an edition of 50. Her other work during this period included a version of Baudelaire’s ‘Flowers Of Evil’, which remained unheard until it was released last year by Andy Votel’s Finders Keepers label (which also reissued ‘Voices Of Packaged Souls’ in 2012). She secured a few commercial jobs too, for educational films and adverts, but touting her music around San Francisco was a dispiriting experience.

“I’d play my reel and people would ask, ‘Terrific music, did your husband write it?’.”

Increasingly depressed by this sort of reaction, Ciani turned her back on music altogether for a while, switching her attention to furniture design instead. Six months later, she was back at the Buchla and had moved to Los Angeles, believing it was the place to be to develop a career in music. She landed some work in LA, including a job on a sci-fi TV show called ‘Search’ (it was called ‘Search Control’ when it aired in the UK), but in an uncanny echo of Daphne Oram’s frustrations at the BBC, she found herself hired to provide sound effects rather than as a composer. She also began to explore an interest in live performance at this time, but it soon became clear that the LA audiences didn’t share her enthusiasm.

After a couple of years, she realised that LA was not, after all, the place to be. She started thinking she should maybe head back east. But she was going to need all her reserves of stubbornness and resolve to get through the next chapter of her life.

In 1974, Ciani was invited to New York to perform a live Buchla concert at an art gallery.

“It was for a sculptor who was having an opening at this very prestigious Fifth Avenue art gallery,” she explains. “I went there and I didn’t go back. I brought my Buchla and I fell in love with New York. I didn’t have the money to bring my stuff from LA, so I put it all in storage. It was like a time capsule when I finally got it back. It was five years later and I didn’t need any of it any longer. So there I was in New York with just my Buchla, loving the energy of the place, the feeling that anything is possible, everything is possible.”

At first, she stayed at the loft apartment of the art critic for Time magazine. A little later, she bunked down at Ornette Coleman’s loft. Later still, she moved into Philip Glass’ studio.

“It was a wonderful time. I gave Philip lessons on the Buchla. He was very studious, but it didn’t take. Ornette Coleman didn’t know what the Buchla was, but when he saw it he thought, ‘Wow, I want this! I want this girl in my sessions!’. So I would be in the room with him while he recorded. I don’t know why.”

Again, she tried to land a record deal. Again, no one was interested.

“No way!” she laughs. “They weren’t ready for this at all. They’d ask, ’Can you sing? Can you play the guitar?’. No. The record labels looked backwards. They have a hit and they want another one like that.”

Although she was “surviving”, as she describes it, she was essentially homeless and relying on couch surfing, having a great time but not making any money. And then she got ill.

“I was very, very ill. The whole world kind of collapsed. Nobody knew what was wrong with me.”

It was an infection, caused by an IUD she’d had fitted just before she’d left Berkeley for Los Angeles. While she was in LA, she had collapsed and been hospitalised for two weeks. The IUD was removed, but an infection lingered undetected.

“Then I went to New York and I kept having these bouts of… I couldn’t stay awake. Anyway, I had an infection and nobody knew it. So for five years, I’d go to my gynaecologist – and here’s another indicator of the time – and I would say, ‘I’m so tired, there’s something wrong with me, I don’t know what’s happening’, and he would say, ‘Oh, you must be having boyfriend problems’. Like you have a psychological problem. You’re a woman, you’re a fragile, dysfunctional being. The day I went by emergency into the hospital, five years after I got to New York, was the same day I’d seen my doctor, and he’d said, ‘There’s nothing wrong with you. Go see a psychiatrist’. I walked out of the office and a block later I fainted on the street, and got taken to hospital.”

This was the catalyst for Ciani to shift her focus once more.

“I was sick and I was starving,” she says. “And I bootstrapped the whole thing by realising that I could make money in advertising. I woke up one day and said, ‘Where’s the money?’. So I started knocking on doors.”

Get the print magazine bundled with limited edition, exclusive vinyl releases

The timing was right this time. NYC’s advertising industry was the hippest in the world and was open to Ciani’s electronic sound.

“Advertising wants to be different,” she explains. “They don’t want what’s already been, they want new. So I was perfect for them. They loved me! They wanted it. They didn’t even know what it was, but they wanted it.”

The New York ad guy who brought Ciani into the commercial fast lane was Roquel “Billy” Davis. Davis was a songwriter and music producer whose pedigree included hits for Motown and Chess Records. He’d been sucked into the world of Madison Avenue advertising a decade earlier, hired by the McCann Erickson agency to write jingles and produce music for them. He was also tasked with tempting artists into the studio to sing for big-name brands, the biggest of which was Coca-Cola. It was Davis who had been responsible for the music for the 1971 ‘I’d Like To Buy The World A Coke’ campaign (memorably credited to Don Draper in the finale of the TV show ‘Mad Men’).

The first time Ciani met Davis was at a session to record a radio advert for Coca-Cola. She’d been hustling for work and turned up on spec after Davis had cancelled several scheduled meetings with her. The ad needed a second or two of blank space filling, and Davis asked if Ciani and her Buchla could provide something. She came up with what might be her best-known work – the sound of a Coke bottle popping and the pouring of the beverage. It turned out that the version she created more closely matched what we imagine than a recording of the real thing, if you’ll excuse the pun.

Ciani’s sound design was beamed into millions of homes around the world, and the ad’s success led to more work in TV and radio advertising in the early 80s. It’s one of the reasons she’s been described as “the Delia Derbyshire of the Atari generation”. Like Delia Derbyshire, another woman whose work was unknown to her, Ciani was behind the scenes, diligently and obsessively creating electronic sounds that would anonymously reach the ears of more people than any pop record.

“Here I was leaking all these electronics into mainstream culture and I wasn’t thinking of it that way,” she says. “See, the thing for me is, I couldn’t even imagine a world where electronic sound wasn’t a big part of it. My frustration in those days was because I thought it was just around the corner. I thought everyone was going to have one of these instruments. Every restaurant was going to be filled with spatial sound. It was going to be indigenous. I used to have the Buchla on all the time, generating an atmosphere in the room, and I thought, ‘Everybody’s going to have this’. It was very disappointing and frustrating.”

After the Coca-Cola ad, Ciani’s stock rose considerably. She even started making appearances on popular TV shows, the latest electronics wizard to baffle the likes of David Letterman and the American general public with music coming out of machines.

In 1982, Ciani recorded an album on her own coin, ‘Seven Waves’, which was released in Japan by Victor/JVC and picked up in the US by Finnadar, a neoclassical label distributed by Atlantic. Finnadar had released albums by Stockhausen, John Cage and its founder İlhan Mimaroğlu, the Turkish composer who was on the landmark ‘Electronic Music’ album in 1966 with Cage and Luciano Berio.

Ciani was having success as a sound designer and a composer, and she was also gaining an audience for her live work, which was (and still is) where her main interest lay. She found an agent who promoted her as a live Buchla performer. It was all looking peachy. But then the Buchla system she had built up over the years broke down.

“I sent it back to Buchla,” she says. “Buchla returned it to me and it came back broken again. Don Buchla actually came to New York. He brought schematics, but nobody could understand them. Nobody could understand the machine.

“And then at some point in the 80s, half of it disappeared. I stored it in a recording studio and it would follow me in a truck when I did session work. But I arrived at one session and only half of it was there. And I thought, ‘Well, OK, the truck driver left it on the street, somebody stole it, and it’s probably in the East River’.”

She later found out that it had been stolen from the studio. In a convoluted series of events, she was reunited with the missing parts of her system 20 years later with the help of Jack Dangers. But that’s a story for another day.

“I had a nervous breakdown,” she reveals. “It was traumatic for me because my machine couldn’t be fixed.”

Like a classical musician whose beloved and unique instrument is mangled beyond repair by rough-arsed baggage handlers, the loss of her synth was devastating. And it provoked yet another radical shift in her life. She abandoned live performance and went back to the piano.

“I never touched a piano for all those years, because I was a spokesperson for the Buchla,” she notes. “I would go and play, and people would say, ‘What’s that, where’s the sound coming from?’. And I would be very patient. I figured that if this was going to go forward, I’d have to listen to what people need to know and be patient and communicate. So I didn’t want people to see me with a piano, because it would short circuit the understanding of the Buchla. Even though that’s no longer the case now, I have a built-in switch. Maybe I do need a psychiatrist, because I really can’t do both.”

In 1986, Ciani released ‘The Velocity Of Love’, put together with contemporary instruments like the Prophet T8 and Yamaha DX7, but well removed from her groundbreaking Buchla work. In the years that followed, her classical roots came to the fore as she developed a sonic world based on gentle and romantic melodies. Most of her releases centred on the piano, some of it explicitly intended for meditation, massage and other new age self-actualisation activities. Her 2005 album ‘Silver Ship’ is an exemplar of the form. It was a musical style that would sustain her throughout the 80s and 90s, resulting in widespread international recognition and success, including several Grammy nominations. Her avant-garde electronic music was, it seemed, well behind her.

In 2012, Ciani was approached by crate digger extraordinaire Andy Votel, who released ‘Logo Presentation Reels 1985’, a limited edition cassette on his Finders Keepers label, reviving interest in her sound design work.

The tape heralded the wider rediscovery of Suzanne Ciani, electronic music pioneer. More of her Buchla archive recordings have appeared since then and she has also collaborated with her spiritual daughter Kaitlyn Aurelia Smith on ’Sunergy’, an excellent album released in 2016. This was also the year that she made her live Buchla comeback with a concert in San Francisco, playing a new Buchla 200e. The show was recorded and issued as ‘Live Quadrophonic’, pressed at Jack White’s Third Man plant. Other Buchla concerts around the world have followed and she is now planning a series of digital releases of her Buchla live sets on her own platform. The first of these releases is ‘Improvisation On Four Sequences At Festival Antigel’, a 50-minute performance from January 2020 at a festival in Geneva, in those far off times before gigs were stopped.

“I’m in constant astonishment that I am now living through the dream that I thought was going to happen 40 years ago,” she says. “I can’t believe that we have reconnected with this thread of evolution that started back then but somehow just disappeared – the idea of an experience, of something tactile and hands-on. And I give the kids credit for this because, on a commercial plane, everybody uses technology as this metaphor for going forward, for progress – technology always gets better and gets faster – but it’s really only a marketing stance! It’s a marketing concept! The kids just said, ‘Wait a minute’. They said, ‘What is vinyl?’ and ‘What is a cassette tape?’. They went backwards, with no logic at all. They put the brakes on.”

It’s as though Ciani has returned to the days of hauling her Buchla around the streets of New York, trying to find an audience for her avant-garde electronic music. The bedrock of her current work is directly connected to her practice in the 1970s, but she’s in a very different place now. The audience is receptive and her work is appreciated.

“The world I’m in is interactive. Live modular performance with a Buchla. Don Buchla’s vision for the 200 – which was what I played in the 70s, and now I have the 200e – was specifically for performance, and that’s a special sub-category. Kids are starting to get into it, they’re interacting and they’re playing live. It’s so fantastic, because interaction is tactile and immediate and it’s not digital! The sequences that I used in the 70s are the same ones I’m using now, even though the sequences sound nothing alike, because this is raw material. The sequencer is marching ahead putting out those notes.”

There’s still a chance that her Buchla could be damaged again or stolen, of course, but she’s prepared for anything this time around.

“My attitude going in this time is, I will do it until it breaks and then I’ll stop. I’m not going to go crazy. I’m not going to make a drama of the whole thing. It’s like, ‘Thank you Buchla, up in the sky, the machine has arrived safely, I can do this concert’. I finally changed my road case last year, from the beautiful, light, white Buchla-designed case to a road case that can be checked as baggage. So it’s more protected than it was.”

As is Suzanne Ciani herself, strengthened by many years of experience and now endowed with a superpower of resilience.

The Delia Derbyshire of the Atari generation.

For more information, visit suzanneciani.bandcamp com