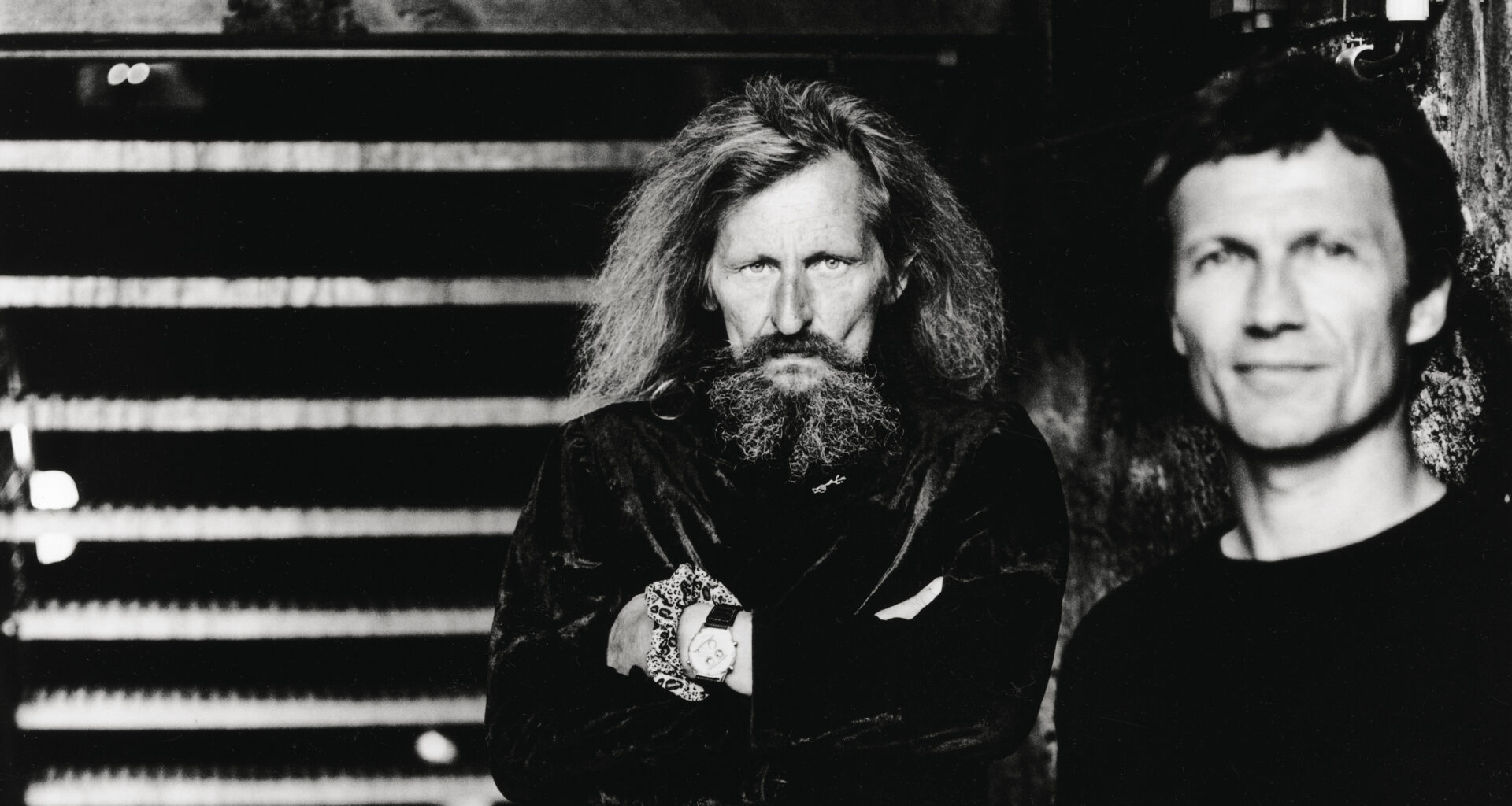

With a new boxset marking the 50th anniversary of their self-titled 1972 debut album, Neu!’s pioneering krautrock groove continues to resonate. Here, Michael Rother sheds light on irascible Neu! co-founder Klaus Dinger, his time with Kraftwerk, and the Bowie collaboration that never quite came to pass

Want to read more?

Sign up to Electronic Sound Premium to gain access to every post, video, special offers, and more. 100%, all you can eat, no commitment, cancel any time.

Already a premium member? Log in here