While everyone else was heading off down the blues road, Tangerine Dream were taking music into another dimension, making records like no one had ever heard before. we explore those early Berlin days and heady underground nights

The Rolling Stones were never ones for synthesisers. There’s footage of Keith Richards trying to play an early analogue synth back in 1969 and clearly all at sea amid the wires and knobs. Mick Jagger, however, did actually purchase a Moog. He had a vague idea that it would be his instrument in the band. But like many rock musicians of his day, he found those black boxes exasperating and ultimately incompatible with the rock ’n’ roll spirit. Jagger sold the Moog and it eventually fetched up in a Berlin recording studio where, in 1973, Christopher Franke of Tangerine Dream bought it for $15,000.

It’s a highly symbolic exchange, for Tangerine Dream represent the point, long before the phrase was coined, when rock made the transition to post-rock.

Tangerine Dream had been in existence since 1967, founded by Edgar Froese, the group’s sole constant member until his death in 2015. With a background in Fine Arts and an appreciation for the innovations of post-war electronic music pioneer Karlheinz Stockhausen, Froese recognised the visual and dimensional possibilities of new music.

An encounter with Salvador Dali, while playing with his pre-TD group The Ones, further convinced the young Edgar Froese that “everything is possible in art”. He was consequently enthralled by the British psychedelic explosion, Pink Floyd in particular. From the Floyd came a sense of the space in which rock sound could travel, exceeding its conventional, blues-bound orbit.

Christopher Franke, who joined Tangerine Dream in 1970, also nurtured a passion for Pink Floyd. An early version of TD played on the same bill as the Floyd at the International Essener Pop & Blues Festival in West Germany in 1969. Franke had been dismayed when Cream disbanded and Jimi Hendrix died, feeling that rock had reached a terminus. He explored jazz and the avant-garde instead, but retained Pink Floyd’s 1969 double album ‘Ummagumma’, whose live sides would be foundational for Tangerine Dream as they further extended the concept of “space rock”.

The unlikely incubator for TD was the Zodiak Free Arts Lab, co-founded by Boris Shaak, Hans-Joachim Roedelius and Conrad Schnitzler. The latter was punk in spirit – he loathed hippies, psychedelia, and the sanguine spirit of the day. He was musically untutored, a conceptualist reared by Fluxus and Joseph Beuys, and he insisted that the Free Arts Lab was painted in black and white only, free of flowery, acid-headed colourisation.

It was here that Froese and the early line-ups of TD played, in an atmosphere of rigorous and focused experimentation, alongside the likes of free jazz saxophonist Peter Brötzmann. Only a couple of years earlier, young West German rock musicians had no encouragement to extend their horizons beyond covering or aping The Beatles. Now, for a handful at least, this was their element, staring light years ahead of Anglo-American rock’s morass of increasingly self-indulgent guitar heroes.

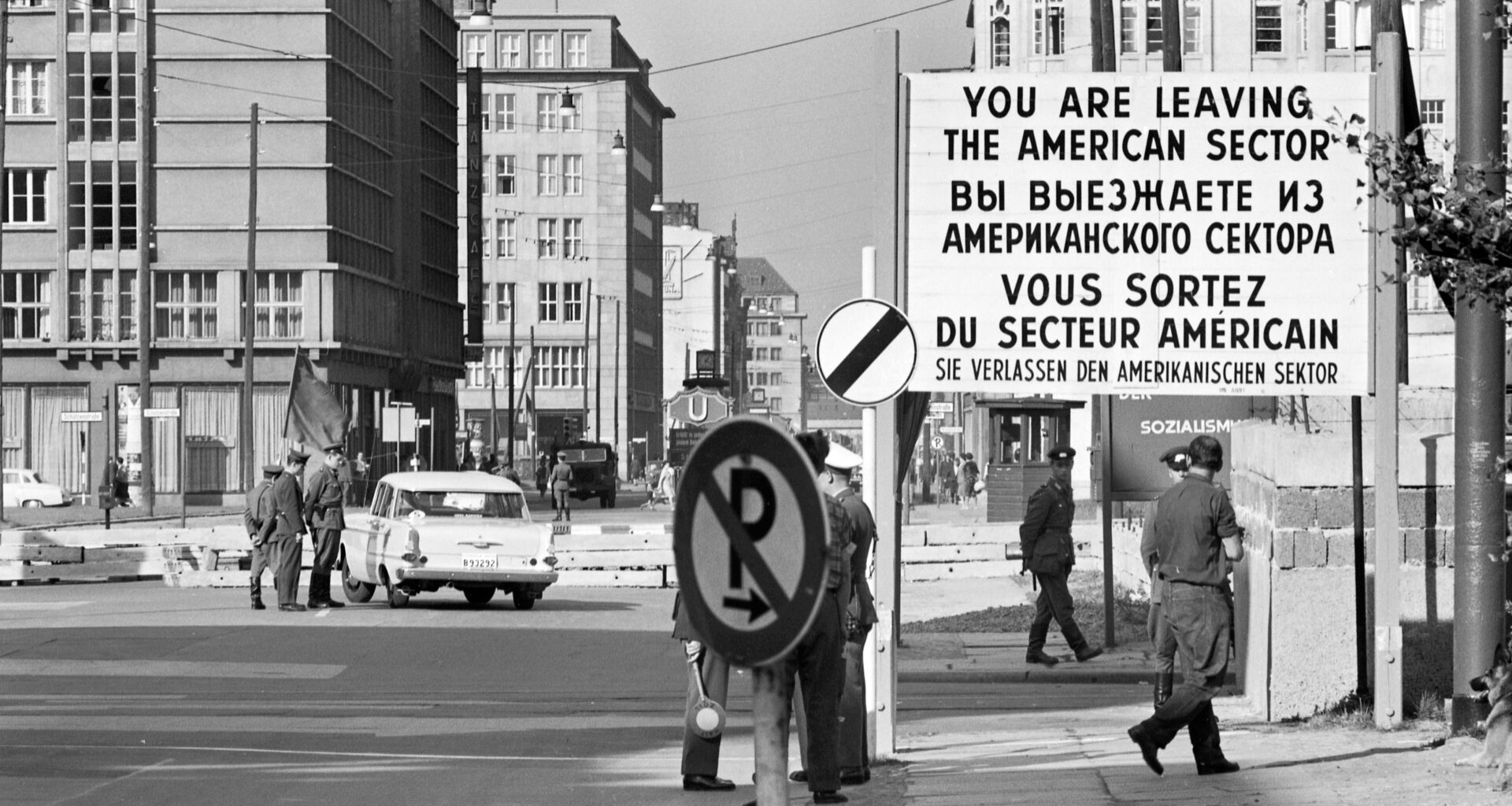

Along with like-minded souls in other parts of West Germany, including Faust, Amon Düul, Can and Kraftwerk, Tangerine Dream were part of a new wave of experimental German music. The practitioners had the common aim of creating fresh musical forms on a clean slate in order to re-establish, if only for their own satisfaction, a sense of German post-war cultural identity untainted by the Nazi past and not indebted to the benign occupation of Great Britain and the United States. Berlin, however, was an island adrift in a broken Germany, so it’s little surprise that the musicians who found themselves there were so disposed to “free” music, mentally at least unconfined by walls and checkpoints.

Tangerine Dream’s debut album was 1970’s ‘Electronic Meditation’. It was released on the Ohr label, founded by one of the organisers of the Essener Festival, who wanted an outlet for the emergent, progressive wave of West German music. Froese was grateful to sign to Ohr, having just had a disastrous attempt to create a musical project with a British singer that had left him out of pocket.

‘Electronic Meditation’ featured Edgar Froese, Conrad Schnitzler and a young drummer called Klaus Schulze. Despite its title, the album did not feature instruments such as Moog synthesisers, which were barely available or affordable in 1970. Its sounds were achieved through devices custom made or modified by Froese, taped and processed effects, and a generally abstract approach to conventional instruments. The result is a collage of sound unmoored from earthbound rock protocols, floating, whirring and droning in the unexplored ether. That the opening track should be called ‘Genesis’ indicated that Froese made no bones about the grandiloquence of his artistic aims.

The triangular arrangement between three such artistically gifted and determined musicians (one of them more an anti-musician) could not hold for long. Conrad Schnitzler left and, after a brief spell with Kluster (Cluster in their noisenik phase), would hammer out an obdurately solo and brutalist career that eventually evolved into a customised proto-electropop.

Klaus Schulze left too, joining Ash Ra Tempel, another group on Ohr’s rapidly expanding roster. They were led by guitarist Manuel Göttsching, whose kosmische visions were similar to those of Froese. On albums such as their 1971 self-titled debut and 1973’s ‘Join Inn’, Ash Ra Tempel achieved a darkly celestial suspension of sound with tracks like ‘Traummaschine’ and ‘Jenseits’, the twisting, glistening and unfurling chords suggesting a remote ambience that anticipates the later work of Brian Eno and Robert Fripp, as well as Tangerine Dream themselves. Schulze wasn’t with Ash Ra long, acquiring a synthesiser from Popul Vuh’s Florian Fricke and spending most of the 1970s creating solo synthscapes, while Göttsching went on to provide one of the cornerstones of techno with the minimal, oscillating “E2-E4”, which was recorded in 1981.

As for Tangerine Dream, they became disgruntled with Ohr Records over what they saw as financial mismanagement. Nonethless, they recorded three further albums for Ohr, ‘Alpha Centauri’ (1971), ‘Zeit’ (1972) and ‘Atem’ (1973). These established the Tangerine Dream firmament, although they had to bring in outsiders such as Florian Fricke and Roland Paulyck to contribute actual synths. Mostly, they achieved their vast, hanging, gaseous effect through modifying and filtering guitars, organs and flutes, disguising their “authentic” origins as best they could. These were huge records, journeying to places that Pink Floyd might have gone had they not opted for the pomped up, muso-driven musings of their “glory” years.

It was in 1974, having at last escaped Ohr’s clutches and signed to Virgin, that Tangerine Dream took another giant leap away from rock into pure electronica. Now armed with their Moog and settled around the essential nucleus of Froese, Franke and Peter Baumann, they released ‘Phaedra’, the eerie, at times wobbly soundscapes based on their initial attempts to get to grips with the still temperamental synth. All of this, however, necessitating elements of chance and improvisation, made for an album that stands as a monument to the artistic helpfulness of technical difficulties.

Around this time, after an epiphany on tour, TD decided to get rid of all their conventional instruments and focus on “doing something completely new”. Their concerts were entirely improvised affairs, the sounds generated from an accumulation of stacked banks of equipment and speakers, later coupled with special visual effects. Initially, their all-electronic music generated hostility. Audience members in Europe threw fruit, even marmalade, at them. In an interview with Melody Maker in 1974, Froese predicted (correctly) that everyone would be playing synthesisers in 10 years time, prompting the Maker journalist to storm out.

There was a certain philosophical pessimism about TD’s music at this time. They were not rock heroes or pop icons or self-styled prog wizards. They functioned onstage like anonymous technicians working at a giant space facility. Their sound posited a universe utterly indifferent to humanity. As Froese himself put it when he was asked about the fate of the planet in 1982, “The earth will recede as the waters rise. The painful thing is that people think it’s being done to them, personally – they have 60, 70, 80 years of life which are so important to them and they cannot see why nature would do this terrible thing ‘to me’. They are only lost, however, in cycles that span hundreds and thousands of years.”

For all this, Tangerine Dream acquired a popularity denied at the time to their krautrock peers. For one thing, their Germanness was less provocative, less problematic than Kraftwerk’s. And despite the synthophobia of the era, it was hard not to be enthralled by the scale of the sound spectacle they presented. Behold! They even played cathedrals, although Froese pointed out with pride that the Vatican had specifically banned them from playing Catholic buildings owing to the possibility of dissolute audience behaviour in sacred places.

In this respect, they were very much of their pre-punk time, when a vast, notional moat existed between musicians – esoteric, highly skilled, engaged in the mystifying – and audiences.

As their sets grew more well-appointed and elaborate, however, TD were suddenly out of kilter with the late 1970s post-punk revolution, in which synths were suddenly cheaper and more compact, enabling electronic music to become democratised. Although they made lots more records and maintained a devoted following, they were no longer ahead of the times.

That said, those first albums, as well as their improvised live sets, some of which are available on CD today, remain timeless, a precursor to dark ambient and a key element in establishing the validity of electronics as a creative and performative tool.