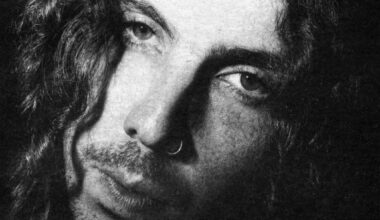

With their second album, ‘Yawning Abyss’, electronic supergroup Creep Show have truly surpassed themselves. From the power of vocoders to AI and “fucking things up”, John Grant, Stephen Mallinder, Benge and Phil Winter wax lyrical

“It takes deep knowledge and time to figure out what’s possible, what can be combined,” says John Grant about Creep Show, the group he’s in with Wrangler’s Stephen “Mal” Mallinder, Benge and Phil Winter.

“Within the framework we were given, we somehow managed to bring all that to bear – all these years of thinking about what’s possible, all these different influences. I mean, I want to hear The Carpenters together with Autechre in the stuff I do. I remember first hearing The KLF with Tammy Wynette. I was listening to it the other day and thinking about how brilliant it was because it was a very strange marriage. And that kind of thing needs to be happening all the time.”

Grant’s own solo and collaborative career has been extraordinary in its range, too.

“He manages to squeeze us in between Elton John and Grace Jones,” grins Benge.

He’s also worked with Hercules And Love Affair, Kylie Minogue, Goldfrapp, Robbie Williams and GusGus.

“John tries to make our stuff poppy and we try to make his stuff experimental,” continues Benge. “I think he would do these vocal manipulations on everything if he had the choice.”

Vocal manipulations are a key feature of Creep Show, and on their second album, ‘Yawning Abyss’, they constitute nothing less than a potential reconfiguration of electropop in the 21st century. Operating at an almost virtuoso, fast-cut level – decision-making at breakneck pace – the treated vocals are the result of a whirlwind, week-long session at Grant’s now sadly dismantled studio in Iceland, with him and Mal using and abusing the vocoder to an extent only previously approached on their 2018 debut, ‘Mr Dynamite’. The pair were evidently pushed on by their mutual admiration.

“It’s hard to be put on the spot by one of your idols sitting there saying, ‘OK, do it, motherfucker’,” says Grant.

“But we have such an easy-going friendship – it was very comfortable, natural, how we transformed it in seven days. That week together was joyous, fun and effortless, despite the trepidation leading into it.”

“We know each other really well,” adds Mal. “We’ve connected and collaborated for years.”

Coming in at an economically old-school 41 minutes, ‘Yawning Abyss’ flourishes in a bed of pristine beats – what Phil Winter describes as “grooves and patterns”, a callback to the apex of the mid-1980s, repurposed 40 years on.

On ‘The Bellows’, the vocal transformations are immediately staggering, generating the sort of soulfulness only machinery can. “You / You feel sad now / And you still don’t know how.” The more combative ‘Moneyback’ follows, dripping with the malign mischief of omnipotent ‘Star Trek’ character Q, popping about from all angles, teasing, pitch-shifting. The title track, meanwhile, feels like a mutation of Scritti Politti, a reminder that for all the unease and menace they evoke, Creep Show are makers of notional pop music, all sweet and dark.

The manipulations reach an apotheosis on ‘Matinee’. Initially, it seems to parody the cadence of The Beatles’ ‘Come Together’, until a chorus line subject to extreme mistreatment and riddled with popping bullets turns it inside out. It’s not that the technologies they are using are so novel – it’s just that no one has chosen to push them this hard before.

The utterly depraved ‘Yahtzee!’ is a delirium of party games carried out “while your children watch their favourite porn”, followed by ‘Bungalow’, on which Grant channels the spirit of Billy Mackenzie on Yello’s ‘Moon On Ice’ with a vocal that is entirely untreated. On an album that makes such a virtue of not only gilding the lily but twisting and tearing it apart, it’s a clever moment of respite.

“John is one of the great singers,” says Mal. “And what a position to be in – to be able to say, ‘I can sing like a motherfucker, but I can also fuck it up any way that I want’.”

This is exactly it. I think of Zapp’s Roger Troutman and his own vocal treatments of what was clearly a magnificent voice to begin with – on tracks like ‘Computer Love’ (as with Kraftwerk on their own identically titled song), there’s a real poignancy in the enhancement used.

The late SOPHIE is another superb example – her use of vocoder and Auto-Tune adds another level of significance to who she was, a kind of “trans” process within music.

“It becomes boring to me otherwise,” says Grant of his own voice. “I mean, fine, I can carry a tune, but… I’ve always been into monster movies. I absolutely love this idea of something transforming – the transmogrification of the human into the robot, the destruction of tissue, the deformation of the voice.

“I cannot get enough of the vocoder. I think it’s one of the great inventions of all time. There’s a melancholy and a longing, a sadness to it that belies its origins in purely technological terms. I think of the remnants of the human race crying out from the past, saying, ‘This is what could have been if you hadn’t been in such a hurry to become this other thing’.

“Decisions about timbre in connection with lyrical content, the juxtaposition of how the voice should sound compared to what the content is. These juxtapositions of sound really make the delivery of specific messages much more… impactful.”

“The vocoder is great because it’s the voice of the machine, but you humanise it,” adds Mal. “I thought there were great choices in terms of the vocal processing. And yes, the vocoder symbolises that effective relationship with the human and technology – it’s good to have it on the record and uphold it as a virtuous thing rather than a con. We live in a world that’s trying to find a balance, and we’re struggling massively with AI. A vocoder encapsulates the perfect harmony of the human and the synthesiser.”

Ah yes, AI. We’ll be coming back to that later.

John Grant and Wrangler first met at the 2014 Sensoria festival in Sheffield, where both were playing.

“We bumped into him in the hotel lobby,” remembers Benge. “And apparently, we’d all been going, ‘Ooh, that’s John Grant over there!’, and John was saying at the same time, ‘Ooh, that’s Mal over there!’.”

In 2016, they came together to put on a set for Rough Trade’s 40th anniversary celebrations at the Barbican, from which arose the germ of the concept that would eventually become ‘Mr Dynamite’. The album followed in 2018 to instant acclaim, with critics taken by its singular combination of the comic and the unnerving. That the follow-up has taken five years to appear has a great deal to do with scheduling issues.

“There are four of us living in different places, so there’s a lot of moving parts,” says Mal. “I’m amazed we got it done at all!”

Covid also laid gruesome waste to their plans for a two-week recording session at Benge’s studio in Cornwall.

“The day after John arrived, he got Covid, and then about five or six days later, I got it too,” explains Mal. “Four days after that, Benge got it. So basically we only got two days’ work done.”

“It hit me like a ton of bricks,” shudders Grant. “I had the razor-blade throat every time I swallowed. After several days, I just felt like crying.”

The studio became a plague house, with the virus victims nursed back to health, their food passed to them under closed doors. Still, all involved believe the long gestation process and their growing partnership have solidified Creep Show into a working entity – no longer are they “Wrangler plus John Grant”.

“That first album, when we were doing the Barbican show, we thought, ‘We want to write music John will be into’ – but we didn’t really know,” recalls Mal. “So a lot of those original sketches we didn’t use because John came into the studio and we started writing from scratch. Today, it’s not a case of ‘We’re going to write music we think works for John’ – it’s ‘We’re going to write music that works for Creep Show’.”

‘Yawning Abyss’ has benefited from the time it took to make, including the numerous lay-offs.

“You leave the material alone for six months, and you come back with completely fresh ears,” says Winter.

“You know when you make a good beef stew and you let it sit till the next day?” asks Grant.

“This record feels like that. You’ve allowed the ingredients to live together and it feels more of a cohesive whole.”

“It’s a testament to what electronic music comprises these days,” chips in Mal. “This whole rich spectrum and a palette of different ways of approaching it.”

With the current debate about AI, it feels like electronic music is returning to its late 1970s phase, when it got mixed up with a pervading anxiety about humanity and technology. Once again, that is uppermost in the public consciousness.

As a distant siren wails relentlessly throughout the interview, both Grant and Mal express concern about this relationship in the 21st century with varying degrees of gloom. Despite their deep, tactile engagement with technology, Creep Show are by no means in thrall to it. Indeed, Mal recalls artist Jeremy Deller’s 2019 acid-house documentary, ‘Everybody In The Place’. In a scene which recreated a rave, people are simply dancing rather than documenting the occasion for social media.

“I guess it’s like, if you haven’t borne witness to it through technology, you haven’t really experienced it,” he reflects.

As for AI… well, that horse has already bolted.

“It’s certainly shaken up some of the complacency about the way we relate to technology and the things we take for granted,” says Mal. “The dystopian elements, thank god, are making us question our relationship with it and where it’s going. What scares me is that I think we’ve lost control already. The human is being eroded in this situation. We’re not even in the conversation anymore!”

“It’s much further along than we understand right now,” adds Grant. “And it’s too fucking late. It’s going to be a mess. You can’t put that toothpaste back in the tube. There’s so much more going on behind the scenes with this. I think horrible destruction will need to stop what’s happening.

“If you see how the giant corporations are manipulating you – selling you the product that gives you the disease and then selling you the solution for it – it’s been going on for decades. It’s already too far gone. With AI, you have people like Elon Musk who are the problem but saying they’re part of the solution. And guys like him will want to sell you the ‘solution’ some way down the road. He’s gone from doing videos warning us about how worried he is about AI… but he’s creating it.”

“It seems to be an attack on creatives, which is alarming,” adds Benge. “Technology’s meant to assist us, not threaten us. I think it will pass, same as with the microchip. They haven’t been planted in our heads.”

In the context of all this, the great thing about Creep Show is that they are extra-human in the face of their machinery. They acknowledge it, engage with it, wrestle with it and wrangle with it, rather than using it to auto-generate. And somehow the playful, unsavoury lines and characters thrown up by Grant in particular amount to a sort of coating of bodily fluids which add a very human gleam to their work.

“That’s important,” says Grant. “Because we are fatally flawed humans grappling with their own reality. Here we are building ideas, trying to have opinions about what’s going on around us while also being sloppy and making mistakes, failing to get our heads around things. And that feels like a truthful way of presenting it.

“Have you ever seen the movie ‘Demon Seed’? It’s about a computer that takes over this woman’s house and tries to impregnate her. The computer has built a contraption to incubate this thing, and out of it comes a baby that looks like a bronze statue – but then things go a step further and you realise it’s a shell. They peel it open and there’s a live, regular baby in there covered in goo. People laugh at it and say it’s ridiculous, but you should watch this movie. It’s ahead of its time and speaks to some of the things we’ve been talking about.”

Horror films were formative for Grant, and so were Cabaret Voltaire. As a big fan of 1987’s ‘Code’, he felt it could have broken the pop barrier for the Cabs, a prospect which seemed tantalising at the time, if perhaps more for Mal than for the late Richard H Kirk.

“‘Code’ was full of undeniable bangers,” enthuses Grant. “For me, it was a bona fide smash, but it didn’t take that way. We understood it in our communities – it was everywhere.”

“It did impact on you because we signed a deal in America, so it was an American record,” reasons Mal.

However, Grant regards its predecessor, 1985’s ‘The Covenant, The Sword And The Arm Of The Lord’, as Cabaret Voltaire’s “crowning achievement”, claiming that “no one has gotten close to that sound”.

“Yes, it’s my favourite too,” agrees Mal. “It was just me and Richard in Western Works. And it was the last record for Virgin. They said, ‘You can’t have much money for this, lads!’. But we channelled what we’d learned from the process of making previous albums – recording with Flood and working in bigger studios on ‘The Crackdown’, for example – and what we’d learned from working with other people. It was more about the abuse than the use of technology. Circuit break, hack it, fuck it up.

“I see kids in the classes I teach fucking things up big time – their spirit’s really good. It’s important that we think about breaking machines to do more things with them. That’s the fun thing about it – ‘breakable technology’.”

‘Yawning Abyss’ is out on Bella Union