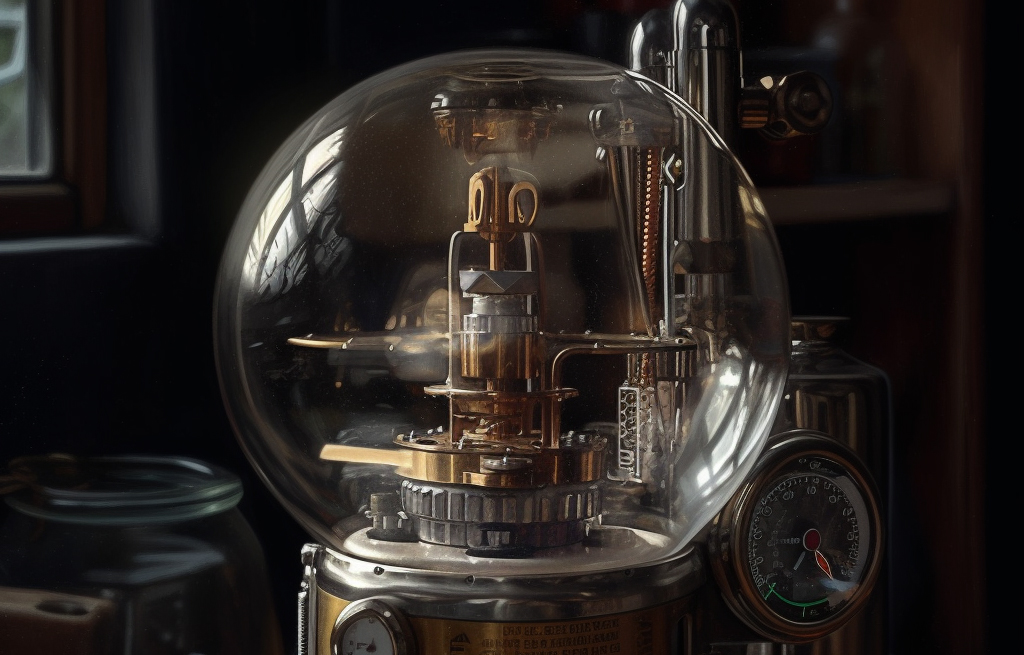

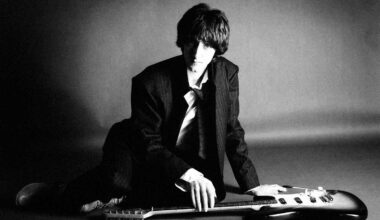

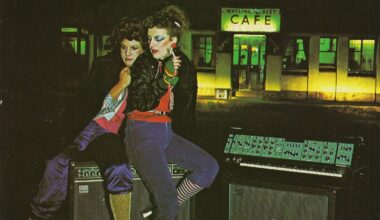

As an early adopter of the iconic Fairlight CMI digital workstation in the early 1980s, pioneering musician and producer Thomas Dolby is no stranger to technological advancement. He reflects on a career full of innovation and muses on how the future of sound may benefit us all

Want to read more?

Sign up to Electronic Sound Premium to gain access to every post, video, special offers, and more. 100%, all you can eat, no commitment, cancel any time.

Already a premium member? Log in here