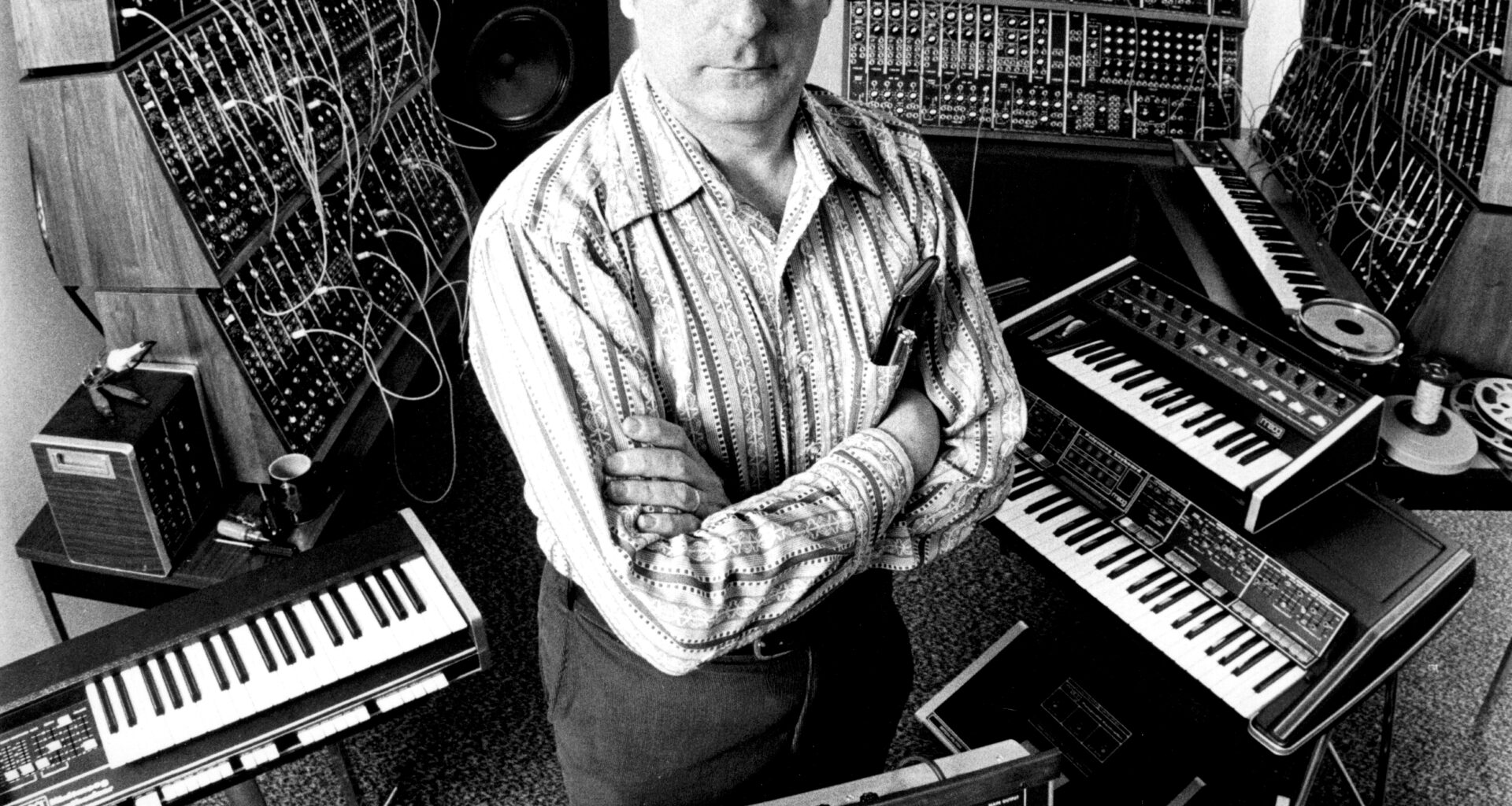

Join us as we open the doors of the RA Moog Company at 49 East Main Street in Trumansburg, New York, and meet the people whose innovative ideas led to the creation of a groundbreaking synth

Want to read more?

Sign up to Electronic Sound Premium to gain access to every post, video, special offers, and more. 100%, all you can eat, no commitment, cancel any time.

Already a premium member? Log in here