In 1958, a mysterious electronic music studio was established at the BBC’s Maida Vale building. sixty years on, an intimate gathering of alumni celebrates the anniversary of The Radiophonic Workshop with a live performance and a post-gig get-together. We pick up the bar tab…

The Royal Albert Hall had been part of London’s entertainment scene for just 20 years when it hosted the first ever sci-fi convention over several days in March 1891. The event witnessed some hardcore Victorian cosplay as fans gathered to celebrate the blockbuster sci-fi novel ‘Vril: The Power Of The Coming Race’. There were stalls featuring magic shows, fortune telling, and even one selling Bovril, which took its name from a contraction of the words “bovine” and “Vril”, such was the novel’s popularity.

If the BBC had been around back then, no doubt someone would have commissioned a radio version of the novel, with a soundtrack of strange sounds from The Radiophonic Workshop.

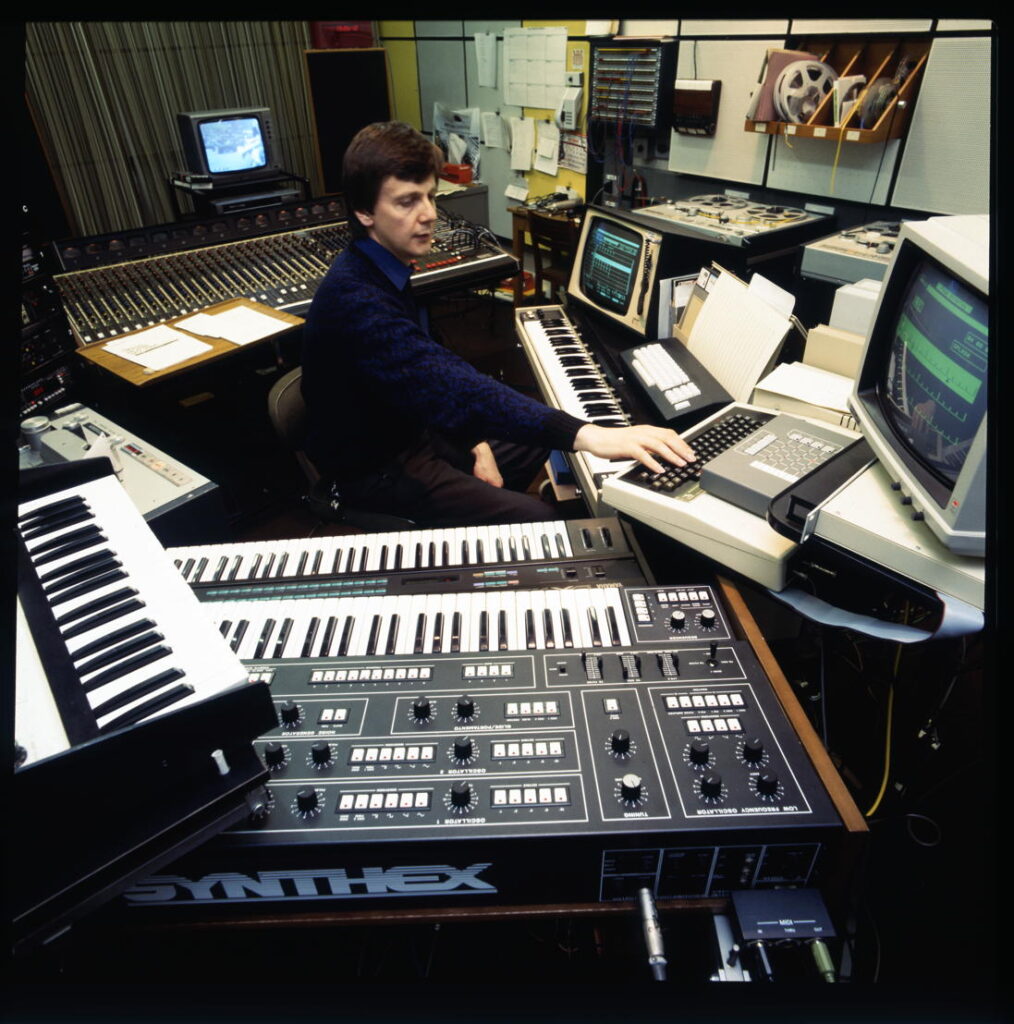

In May 2018, Dick Mills, who worked at The Radiophonic Workshop from 1958 until 1993 (that’s 35 years of shaping the sonic landscape of the nation, for which he surely deserves at least an MBE or something) is sitting in one of the green rooms of the Royal Albert Hall. He’s hanging around, waiting for a rather special Radiophonic Workshop gig that is happening later on in the venue’s Elgar Room. So are we.

“Did you know,” muses Dick, as the band soundchecks a few doors down, “the original Radiophonic Workshop mixing panels came from here. They were built in 1943 for the Royal Albert Hall, and somehow they made it up to the Workshop. We used them for years.”

They didn’t really work properly (adding an input would half the volume of the overall output), but the make-do-and-mend ethos of post-war austerity Britain was, of course, both a necessity and a guiding principle for the early days of The Radiophonic Workshop. The place was full of engineers, inventors and composers, the tripartite skill set often lurking within each Workshop employee. Many of them could turn then-plentiful war surplus electronics into sound creation solutions. Some of the equipment they built was as ingenious as it was eccentric.

For example, reverb effects were achieved with a real reverb chamber, a room in the basement with a speaker at one end and a microphone at the other which would capture the sound from the speaker with the added reflection characteristics of the room.

Then there was the Wobbulator, a test tone oscillator whose output could be varied by a second oscillator through wildly extreme ranges, and The Crystal Palace, which was invented by Dave Young, the second engineer to be employed at the Workshop. Dick tells me Young had been shot down over Hamburg in 1939 and spent the rest of the war in a German POW camp, “six happy years” he chuckles. His invention took up to 16 inputs from sound sources such as oscillators, fed them into four mixable outputs, all housed in a clear perspex box, and created a unique droning organ-like sound.

Later, during the aftershow get-together, The Crystal Palace is described as “a machine of pure genius,” by David Cain, one of the 1960s cohort. He lives in Poland now, and sent a message to his old colleagues from his holiday in Tenerife, to be read out by Dick Mills. I’m standing next to Glynis Jones at that moment, who joined The Radiophonic Workshop in 1973.

“I was terrified of him!” she whispers to me when Cain’s name crops up.

These innovators and creative individuals made it up as they went along, inventing the machines they needed to craft the sounds they could hear in their imaginations. And judging by the noises coming down the corridor from the Elgar Room, that’s exactly what they’re still doing 60 years later.

The ghosts of the Victorian sci-fi convention are long gone, but the Royal Albert Hall’s imposing presence leaves you in no doubt as to this venerable institution’s central role in the cultural sweep of the last 150 years. Fifty years ago, John Lennon knew how many holes it would take to fill it. Like the BBC itself, the place stands for permanence.

The abiding British fascination for peculiar science fiction, the Beeb, The Radiophonic Workshop, the Royal Albert Hall… tonight they’re all part of one long oddball continuum, a hall of mirrors where pasts and futures co-exist, where reverence for tradition sits alongside a urgent need for innovation. As such, The Radiophonic Workshop, “a long corridor with some very drab rooms” as Workshop member Peter Howell puts it, seems like a perfectly workable metaphor for Britain itself.

Tonight’s live performance is a low-key marking of a significant anniversary: 60 years since the establishment of The Radiophonic Workshop at the BBC’s Maida Vale Studios, just a couple of miles to the north of the Royal Albert Hall. Less celebrated is the 20th anniversary of its ignominious closure, officially announced in 1998, but effectively it was over by 1996, when the last Workshop employee, Elizabeth Parker, scrambled to finish the music for Michael Palin’s documentary TV series, ‘Full Circle’.

The evening is intended as an intimate and poignant gathering of fans, aficionados and friends, including a handful of former colleagues beyond the current touring band. In attendance are the aforementioned Glynis Jones and Brian Hodgson, whose first stint lasted from 1962 to 1972, before rejoining in 1977, finally leaving in 1995. Elizabeth Parker (1978-98) isn’t here, but has offered to talk to us a few days later, and David Cain is here in spirit. It’s the most comprehensive gathering of Radiophonic Workshop composers anyone can remember, and it’s likely to be the last.

“We ain’t going to live long enough,” quips Dick, “so we’re doing our own tribute band.”

He’s joking, but later on, making a short speech to the audience, he pays emotional tribute to his friend and former Workshop colleague Ray Wiley, who passed away a few weeks earlier.

Peter Howell and Paddy Kingsland wander into the green room. They’ve finished sound checking. Inevitably not everything is working properly on the stage, which is crowded with gear old and new. Workshop archivist and musical director Mark Ayres pops in. Somewhere in the building is Roger Limb, whose tenure lasted from 1972 to 1995. His work on ‘Doctor Who’ is well known, and his track ‘Passing Clouds’ has the unusual distinction of being used by Prince as the opening atmosphere on the ‘Lovesexy’ album.

Paddy Kingsland started at the Workshop in 1970, Peter in 1974. They both joined the BBC as studio managers, the in-house term for what we might understand as recording engineers.

“You’re operating the equipment in the studio,” explains Paddy, who achieved Radiophonic immortality with his work on the TV version of ‘The Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Galaxy’. “You covered a huge range; you could be doing Jimmy Edwards in a comedy show one day, and the next it would be Gene Vincent. It was a wonderful job.”

Paddy first encountered the set-up when some on-the-job training included a visit to the Workshop.

“I didn’t know much about them,” he confesses. “We’d played theme tunes from the pink album [the 1968 album ‘BBC Radiophonic Music’], with Delia Derbyshire, Jon Baker and David Cain – people often used those at Bush House, the BBC overseas deptartment – and so I’d kind of heard of them via that, and ‘Doctor Who’ of course, but not much else. It looked like fun, and Desmond Briscoe, who was in charge said [adopts plummy voice], ‘If anyone would like to come, you’re very welcome to apply to my office’. So I did. After a few short attachments, they offered me a job in 1971 and I stayed until 1981.”

“I really enjoyed playing tapes that had come from The Radiophonic Workshop when I was a studio manager,” says Peter Howell. “They had special leader tape on them, and it was BASF tape, too – fancy!”

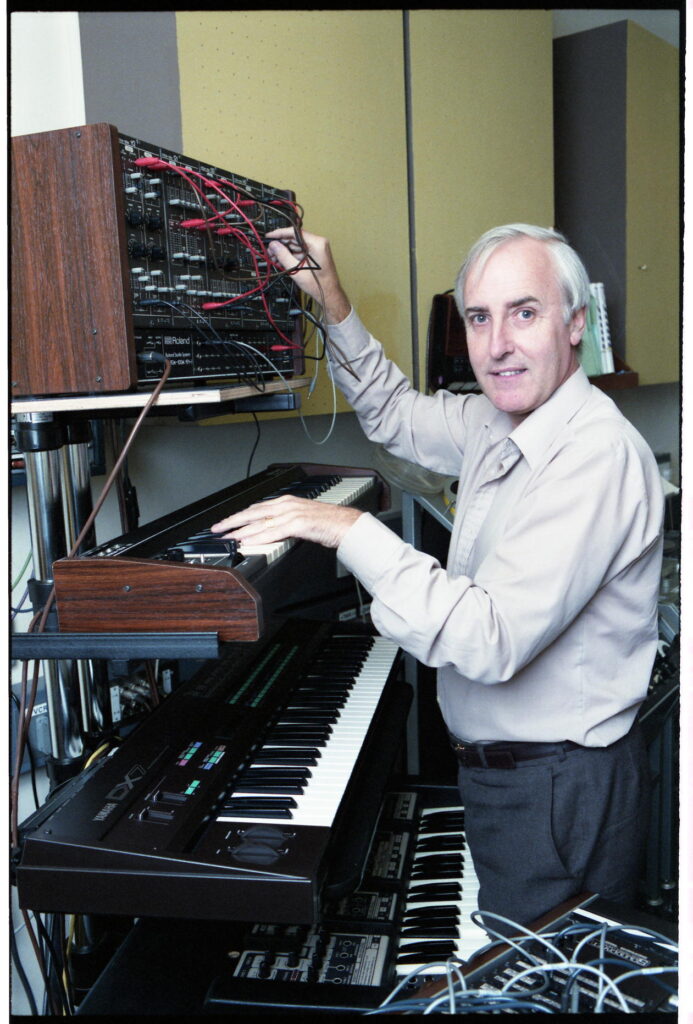

The Radiophonic tapes always sounded great, he says, because they recorded at a higher level than was standard. It was as if they had a special relationship with sound. Which, of course, they did. He didn’t however imagine for a second that he was entitled to go there. His route to the Workshop came via the BBC’s amateur dramatic society, The Ariel Theatre Group. One of the shows the group put on, at The Cockpit Theatre in Marylebone, needed some sound effects for a slide show and Peter, as the audio guy, was pointed in the direction of some “bits and pieces upstairs” to see what he might be able to come up with. In an open room, just left apparently unused in a corner, were two EMS VCS 3 synthesisers. It was the first time Peter had touched a synth.

The piece he put together fitted the bill, and at the aftershow party, someone suggested he approach The Radiophonic Workshop. In those days, it was possible for BBC employees to go on attachment to different departments within the corportation as part of their professional development, and so Peter first joined the Workshop on a temporary attachment in 1973, which became a full-time job in 1974. He was the second-to-last person to leave the place 24 years later.

Despite it being 15 years after the Workshop’s inauguration under Daphne Oram and Desmond Briscoe, the equipment was still a hotchpotch collection.

“It was old BBC stuff, and anything they could scrape together,” says Peter.

Like the old Albert Hall mixing panels.

“The BBC obviously thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be nice to have an in-house department that would do all our funny noises, sound effects and electronic music for us?’,” says Dick. “Whereas Daphne Oram wanted to pursue a more arty line and create music and treatments for their own sake.”

Oram and Briscoe were the department’s first employees in 1958. It had taken two years since the idea was first proposed for the BBC to actually create The Radiophonic Workshop. The BBC was stung into typically sluggish action by an internal report about the innovations in sound taking place at the electronic music studios in Paris and Cologne.

In the 1950s, the two European studios represented opposing schools of non-traditional music making; electronic music created with oscillators, and music created by tape manipulation. Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry in the Paris studio of French national broadcaster RTF were tape music pioneers, while in Germany’s WDR studio efforts were focused on electronics.

These two heavyweights of the new European electronic music movement were funded by their respective governments to produce serious experimental work for its own sake, and spent quite a lot of energy denigrating each other’s efforts. The French thought that the Cologne studio spent far too much time producing “elementary laboratory experiments”, while the Germans discounted the musique concrète made in Paris as merely “fashionable and surrealistic”, haphazardly put together.

The BBC’s Radiophonic Workshop would not have the luxury to indulge in such snooty academic mud-slinging. It was a service department, making music for whoever needed it.

“Whereas people like Pierre Schaeffer and Mr Stockhausen would labour for months or even years over a piece until they felt it was right,” says Dick, “we had to labour for days over a composition that our customers wanted right. Anything we experimented with or originated was always someone else’s commission.”

Dick describes the typical response as, “Do you want it good, or do you want it by Monday?”. More often than not, it was delivered on Monday, and it was also good. Like one of Paddy’s cues for ‘The Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Galaxy’, among his finest work in his own opinion, which was needed at ridiculously short notice for a Vogon spaceship scene. He wrote it as he played it, the composition took all of a handful of inspired seconds.

Mark Ayres remembers Malcolm Clark (who was at the Workshop from 1969 to 1994), telling a story from when he was sent to represent the BBC at an international electronic music studio symposium.

“Someone from one of the other studios very proudly announced they had finally finished digitising their entire output of the previous 50 years, and pulled out a couple of CDs from his bag, put them on the desk and said, ‘There it is!’. Malcolm took one look and replied, ‘We do that before breakfast!’.”

Perhaps to avoid the kind of temperamental jealousies that had sprung up between Paris and Cologne, the BBC stipulated that The Radiophonic Workshop should be staffed by engineers rather than composers. Oram and Briscoe were both engineers and composers.

According to Dick Mills, Briscoe always wore sandals “for medical reasons”. He was even excused boots when he was in the army, he says, and when he had to wear evening dress, he had a pair that were painted black.

Oram was a BBC studio manager with a keen interest in avant-garde electronic music. She’d already visited both the RTF and WDR studios, and had made quite an impact with a piece of electronic music she’d composed for a BBC radio play using filters she’d built herself with surplus sine wave oscillators, recording between midnight and four in the morning in studio downtime.

As Dick says, Oram’s vision for a studio to challenge the dominance of Paris and Cologne, where electronic art could be pursued for the cultural benefit of the nation, soon evaporated. The reality was that the BBC wanted a special effects assembly line. Oram left in 1959 to pursue her Oramics machine, a revolutionary device that could convert visual information into electronic tones.

Despite Daphne Oram’s disillusion, the Workshop soon hit its stride and was perfectly placed at the Maida Vale complex. The building housed a huge orchestral studio, and dozens of smaller facilities. Elizabeth Parker remembers its creative atmosphere fondly.

“In its heyday, it was an amazing place,” she says. “You’d find yourself standing next to Bon Jovi or Bill Nye or Micheal Nyman or André Previn, you never knew who you would see in there, it was fantastic. Muhammad Ali was there once, he just came around to have a look!”

And the John Peel sessions were recorded there, of course.

“Oh yes,” she chuckles. “They went on through the night, and if I was working late in the evening, you’d sometimes start to smell marijuana coming up through the floorboards, which was actually really rather nice!”

“If we wanted to base particular music tonalities on a given instrument, and there was nothing that we could use to synthesise that,” says Dick, “you’d just stick your head through the window of Studio One and pick the bloke playing the instrument of your choice and say, ‘Oi, do you want to do a few experimental live recordings?’. And before too long, he’d be saying, ‘Why do you want me to put my mouth over the other end and suck?’.”

And if that sounds a bit ‘Carry On Up Your Oscillator’, Paddy Kingsland’s anecdote does rather compound the image…

“In the early days, the classical music department, Radio 3 types, would get letters from people with names like Herr Hernholz-Resonator or something, who were experimenting in electronic music in Germany and wanted to visit. They always pushed them onto Desmond. They’d arrive with a pile of tapes and say, ‘Maybe I could play you my latest piece’, and they’d bung it on the machine.

“Eventually, after a few of these visits, Desmond had a bell push installed under his desk, which he’d operate with his knee, and you could actually hear it outside – bzzz. The secretary had been briefed to not come in straight away, but after a few minutes, to come in and say, ‘Oh Desmond, you’re wanted urgently at Broadcasting House’, and he could say, ‘I’m so sorry, we’re going have to switch off, thank you very much Herr Resonator, see you another time’.”

Tonight’s show, despite the problems with the headphone monitor mix which was, Mark Ayres tells us, running a quarter of a beat behind the main mix, is rapturously received. As a band, The Radiophonic Workshop mix crowd-pleasing hits, like the extended ‘Doctor Who’ theme that closes proceedings, and a chunk of ‘The Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Universe’, complete with nostalgia-inducing excerpts from the TV series, with more radical pieces like ‘Electricity’ and ‘We Would Not Be Here’, a track featuring Stephen Hawking’s synthesised voice, sent by the great scientist himself quite unexpectedly when they wrote to him asking permission to quote a few lines from ‘A Brief History Of Time’. The high point is a “re-improvised” section from their 2017 album ‘Burials In Several Earths’.

In the audience are Chris Carter, Cosey Fanni Tutti, and the actor Caroline Catz. A familiar face to fans of ITV’s ‘Doc Martin’, Catz is set to play Delia Derbyshire in a forthcoming film about her life. When the show is over, the crowd starts to disperse, leaving a handful of Radiophonic insiders. One of them is Glynis Jones. She’s just been chatting with Roger Limb.

“I haven’t seen him for 40 years!” she says, slightly astonished and clearly delighted.

Glynis Jones started at the Workshop in 1973. She’d been a studio manager at the BBC World Service in Bush House, and before that was in the music division. It was Roger Limb who had encouraged her to join the Workshop on attachment. She did, and never returned to Bush House. As she joined, Delia Derbyshire was leaving.

“On my first day there,” she remembers, as we quaff white wine, “I was put in a room with a VCS 3 and three reel-to-reel tape machines, a big oscillator and a load of Welsh poems, and told to produce music for them. I absolutely adored it.”

Jones took to her life as a Radiophonic Workshop composer like a duck to water. She lived nearby and the composers were allowed to come and go as they pleased, so she could record at night if she wanted, which she often did. For several years, she blithely went about her composing duties at the Workshop without much concern.

“I never had anything rejected,” she says. “For the first three years, I just went into the room and did it quite innocently. Then suddenly it started becoming more and more important to me, and more stressful.”

For Jones, a dawning realisation of the importance of her work undermined her confidence. In what we’d now recognise as a stress-related reaction, probably to the never-ceasing treadmill of deadlines, she hit a brick wall and quit in 1975.

“I was only young, and now I can look back and see what happened,” she says, sadly. “I wish I hadn’t left, really, but it was a real crisis point.”

Nowadays, there would be a system for employees to spot the warning signs and seek help. As it was, she “dropped out”, abandoning music. Recently, however, she’s started playing the viola da gamba and thinks she might be able to do something with it.

“It’s difficult though, because I’m so analogue and tape loopy… I saw someone explaining on the TV recently how to run two tape machines in sync, it made me feel like I was out of the stone age,” she laughs.

Brian Hodgson, who worked closely with Delia Derbyshire, addresses the Royal Albert Hall aftershow gathering.

“I joined the Workshop in 1962,” he says. “I remember how Dick welcomed us into the Workshop, which he did with every one of us, and we all benefited from his experience. I arrived shortly after Delia and she was really quite stunning in every way. She was elegant, beautiful and talented, and I thought, ‘Shit, she’s so wonderful’. That was before she turned into a sort of funny old hippy, stinking of snuff and booze, but her talent just shone through, and I hope the film that Caroline Catz is going to do will help perpetuate the wonderfulness of Delia.

“I left, formed my own company and then went back later on to manage the Workshop,” he continues. “I felt so privileged, but managing them was a bloody nightmare. All prima donnas! As an ex-prima donna myself, I know how difficult that can be. But the sheer talent, you’ve heard it tonight, was just wonderful. I’d like to say one more thing, about Mark Ayres. When he was a kid, Dick encouraged him. Without Mark, the Radiophonic library would not exist, he found it as the BBC were about to put it in the tip somewhere. And without Mark, who I gave all these tapes to, there wouldn’t be a Delia archive either. A toast, to the new incarnation of The Radiophonic Workshop, of which I’m very proud, and a great fan. To 60 years!”

A picture emerges of a group of mavericks, none with “any ambition whatsoever”, according to Dick Mills. Or rather, no career ambitions beyond making music, creating new sounds.

They were all, it seems, allergic to the idea of progressing through the ranks at the BBC into management. When the role of manager did become vacant, when Desmond Briscoe retired, Dick says no one was interested in applying for the post, “although deep down we all felt we should”.

Some explained why they wouldn’t be applying, others went on holiday and “hoped it would all be past by the time they got back”. Brian Hodgson was “slowest out the door” and got the job, but no one wanted to leave what he calls the creative ranks.

“I’m eternally grateful to Desmond and Brian for tailoring the studio space around each of our own peculiar talents,” says Dick. “We were genuinely looked after, we were appreciated.”

There’s an idea of the Workshop that is almost hackneyed, a clichéd rose-tinted revisionism that it was an idyllic enclave of eccentric noise makers, keeping irregular hours, living the life of out-there composers, untethered to real life, in a low-level rebellion against (and also cosseted within) a strangely indulgent yet strict BBC (the Auntie Beeb nickname makes sense here).

And it turns out it’s pretty much true.

Mark Ayres, who brought together the touring version of The Radiophonic Workshop, reveals a titbit as he talks about the genesis of the live Radiophonic Workshop. The first performance was in March 2002 for an art project called ‘Generic Sci-Fi Quarry’, a celebration of British sci-fi and its reliance on quarries to stand in for alien planets. The piece took place in an actual quarry with a soundtrack by Ayres, Brian Hodgson, Peter Howell and Paddy Kingsland.

“The artists approached me in 2001 and asked if I could get some former members of The Radiophonic Workshop involved,” says Ayres. “So I spoke to Peter, Brian, Paddy and Delia. Delia was quite interested in doing it. I had a long conversation on the phone to try and persuade her that it might be a good idea. She asked me to put it in a letter, which I did. l got the letter back unopened after she died. It was an enormous shame.”

The event was the spark that eventually led to the creation of the current live band. Had Delia lived, perhaps she would have been up on that stage tonight too.

As we leave, a summer storm, the likes of which we’ve rarely seen before in the UK, erupts directly overhead. Lighting flashes streak across the night sky every few seconds creating a surreal shift in shadows. It’s a stratospheric light show with accompanying noise and rain so intense that by the time we reach a bus stop just 20 metres away, we’re soaked through. It seems like a fitting tribute to The Radiophonic Workshop by way of a cosmic reference to White Noise, Delia and Brian’s spin-off project with David Vorhaus, and their album ‘An Electric Storm’.

Perhaps Delia is summoning up one last electric storm.