Forty years since the release of Kraftwerk’s ‘Radio-Activity’, we take a close look the dark horse of the five-album masterwork the band produced between 1974 and 1981

Forty years ago, Kraftwerk’s fifth album ‘Radio-Aktivität’ was released, followed in short order by the UK version, ‘Radio-Activity’. It was the first Kraftwerk album to have both German and English lyrics, and the first (but not the last) to be stuffed with puns, double meanings, ambiguity and a lightness of touch that belied a subtle complexity. The album seemed almost to poke fun at the burgeoning (especially in Germany) anti-nuke movement by celebrating nuclear power (or at least, not condemning it), while making jovial and literal observations about radio waves, wrapped up in a series of tracks that swerved between all-electronic pop, abstract sound design and musique concrete. As an album from four German guys wearing suits and short hair in 1975, when the top selling artists in the UK included Status Quo, Rod Stewart and the Bay City Rollers, it was a pretty bold bid for pop stardom.

“It was like our dedication to the age of radio, and radiation at the same time, breaking the taboo of including everyday political themes into the music,” Ralf Hütter said in 1981 during an interview with – what else – a radio station (in this instance the British local station Beacon Radio).

But beneath the surface of a paean to the golden age of radio lurks a more unsettling interpretation of the album’s themes, never mind the nuclear energy controversy: the radio set featured on the cover was Nazi-era technology, the DKE38 or the Volksempfänger’s smaller variant, the Deutscher Kleinempfänger. The radio set, which was also known as ‘Goebbels schnauze’ (which roughly translates as ‘Goebbels’ gob’, Joesph Goebbels being Hitler’s Reich Minister of Propaganda), was originally adorned with the Nazi’s swastika and eagle logo, and was purposefully lumbered with a limited reception range of 200km so German citizens would not easily be able to access non-German broadcasts, while receiving Nazi propaganda with crystal clarity.

In that context, the ambiguous lyrical mentions of radioactivity “in the air, for you and me” apparently both innocent and uplifting, becomes imbued with deeply sinister undertones. Nuclear power was going to provide cheap, clean electricity and radioactivity enabled a huge breakthrough in medical treatments, but is dangerous to the point of threatening the extinction of mankind; radio, that helped to popularise Kraftwerk across America, and the joyful life-affirming rock ’n’ roll revolution before them, but was used to spread the evil propaganda of the Nazi regime in Germany.

Later, Ralf and Florian came off the fence and made explicit their feelings about nuclear power, adding a list of locations of nuclear accidents to the lyric in the intro of album’s title song when it was played live, intoned by the scary Kraftwerk robot voice, as well as the word “stop” before every mention of radioactivity, and a new couplet: “Chain reaction and mutation / Contaminated population”. Perhaps radioactivity itself is a metaphor for Nazism, casting it as a spreading darkness, that poisons all life. Maybe that’s too literal an observation, or too convenient, or just lacking subtlety, but there’s no doubt that ‘Radio-Activity’ is, both literally and figuratively, the darkest album in the Kraftwerk katalog.

In 1974, post-‘Autobahn’, hopes were high in the Kraftwerk camp. They’d left the august but stuffy label Phillips, which saw their albums released in the UK by the label’s hip and slightly underground progressive rock subsidiary Vertigo. “We were a little embarrassed all the time with the German record company,” said Ralf Hütter in 1981. “At that time they didn’t understand where we were. They were in Hamburg, which is a very reactionary German town, very historically-oriented.” As a side note, Kraftwerk were the third band Phillips signed, their labelmates Ihre Kinder and Frumpy, were bands who were essentially prog rockers firmly at the hippy end of what would later be dubbed krautrock by the ever-sensitive British music press.

Ralf and Florian had added their signatures to a new record deal with EMI and sister label Capitol in the United States, the home of The Beatles. And, like The Beatles with the Apple label, they’d been given their own vanity imprint – Kling Klang Schallplatten. Düsseldorf’s Fab Four were going places and the reason for all this change and optimism was the surprise hit in the UK and the USA that Kraftwerk had enjoyed with the radio edit of the previous year’s ‘Autobahn’ track.

The success of ‘Autobahn’ meant that Kraftwerk toured outside Germany for the first time, performing to unsuspecting audiences in the UK and, crucially, the USA. The bricolage of musicians that had come and gone during the band’s experimental and hairy early years had inevitably evolved into a stable four-piece of clean-cut young men in suits. Ralf and Florian had been joined by Wolfgang Flür and Karl Bartos as full-time band members and the outfit had achieved the clean symmetry of a four-piece pop group.

Everything was set fair for Kraftwerk to do some serious business. ‘Autobahn’ had shown the world – and Ralf and Florian themselves – that there was an international market for short, catchy electronic pop songs, a lucrative one outside of the long hair prog types who made up most of Kraftwerk’s audience prior to the single’s success. They just needed to create the right concept for the sleek new visionary Kraftwerk to introduce itself to the record buying public.

It was in America that the concept for ‘Radio-Activity’ started to come together. According to David Buckley’s book ‘Kraftwerk Publikation’, Ralf and Florian first encountered the term “radio activity” in Billboard magazine, where America’s all-important airplay charts were collated under that title. Our research turned up a section in 1975 called Radio Action, but the term “radio activity” was used repeatedly in the magazine – and the wider industry – to describe which records were hits with the nation’s hundreds of radio stations. The USA then, with its network of all-important music radio stations encountered on the band’s first US tour in April and May of 1975, was the key to Kraftwerk’s future direction and ambition.

“Sometimes you have to leave your country and gain success somewhere else,” says Wolfgang Flür of the American tour. “When we played the Beacon Theatre, the German papers who called us ‘cold’ and ‘idiots’ before, came across the ocean because we were playing in New York, so they thought, ‘There must be something to them after all’. And then suddenly it was, ‘Our boys electrify America! We knew all along!’. And when we were there, Ralf and Florian had to give many radio interviews, it was this radio activity that gave them the idea.”

It’s also noteworthy that Emil Schult accompanied the band on the US tour. Schult was Kraftwerk’s confidant, sometime lyricist, one-time member (he played guitar and electric violin on a short summer tour of Germany in 1973) and general art consultant. Hütter once described Schult as the band’s “guru”, and he remains a Kraftwerk insider to this day.

Schult was first brought into the Kraftwerk sphere by Florian Schneider who saw him playing an electric violin in a band. He had studied under Joseph Beuys at Düsseldorf’s Kunstakademie (at the nearby Music Academy, the sound that rang out to alert students of break time was composed by Stockhausen). Beuys, a former Luftwaffe pilot, was a radical tutor and exposed his students to the idea of art as performance and the artist’s commitment to their work. Schult has said that “Bauhaus was omnipresent in Beuys’ classes” and the influence of the Bauhaus has often been noted in Kraftwerk’s output. Schult had been to the World Expo in New York in 1964 and seen its ‘Futurama II’ exhibition, General Motors’ extravagant sci-fi vision of life in the future, a large-scale model/ride that served to show Americans how motorways would connect their cities of the future.

“I started to buy vinyl electronic music from Phillips,” Schult recently told Electronic Beats magazine. “There were only a couple of albums available in the 1960s, and I played them to death. It seemed as if it took ages before more than just a few bands started to experiment with synthesisers.”

It’s pretty obvious that Schult’s influence on Kraftwerk cannot be overstated, and possibly his experiencing ‘Futurama II’ 10 years earlier even had a hand in Kraftwerk’s ‘Autobahn’ breakthrough. Schult also brought humour to Kraftwerk, first with the artwork for the band’s third album, ‘Ralf And Florian’, in November 1973. The record came with a poster of amusing comic drawings and photo collages and above a black and white portrait of Ralf and Florian, which looks like a satirical take on a stiff captains of industry portrait, their names were rendered in classical German gothic typeface. Perhaps their first wry joke at the expense of Germany’s international image.

The theme for the new album was discussed on the flight home after the US tour, the band and Schult exploring the ideas that would become ‘Radio-Activity’.

“We had often talked about radioactivity,” says Wolfgang, “about its benefits and negative impact on human societies. And it came up again on the plane when flying back from the US that year. Ralph was sitting next to me. We spoke the whole flight about the results of the tour and our future. Ralf was still studying architecture at Aachen TH [technical high school] and I was still an interior designer at a Düsseldorf architect’s office. Ralf promised me: ‘Wolfgang, you don’t need to worry about the future. We both don’t need to work in any architect’s office in the future. We’re Kraftwerk and will be very successful’.

“Then he explained the new theme of the activities of the mid-band [FM] radio stations in America that made us famous because they had played our ‘Autobahn’ song all over the country and made it a big hit, and that this radio communication theme would be the new theme for the next album. I liked this idea immediately. However, I still had to work in the architect’s office a while longer because my fee in Kraftwerk was lousy in those years. I never had a contract of employment, I was always a freelancer.”

But the trigger for the album’s concept – radio and its central role in the popularisation of pop music – was already an established idea in the Kraftwerk world. It featured in the lyric of ‘Autobahn’: “Jetzt schalten wir das radio an / Aus dem lautsprecher klingt es dann” [“Now we put the radio on / From the speaker comes the sound”]. And when so many of the few carefully chosen words they did sing on that record were devoted to the idea of radio, you know it was a powerful image for them. “We were boys listening to the late night radio of electronic music coming from WDR [Westdeutscher Rundfunk] in Köln… they played a lot of late night programmes with strange sound and noise,” Ralf Hütter told Beacon Radio.

Flür also makes a romantic mention of listening to the radio as a child in his autobiography: “With the light in our room having already been put out,” he remembers, “only the magical green glass pane of the station indicator would weakly illuminate the chest of drawers on which the radio stood”. He later saw a transistor radio in a shop window, and saved up for weeks to buy it. “It was made of white Bakelite, with a tuning disc set behind a magnifying glass. It was so modern and made me look good in front of my friends. It had an earpiece so I was able to sift through the stations in bed at night, hidden from my brothers… it brought new sounds from faraway places to me.”

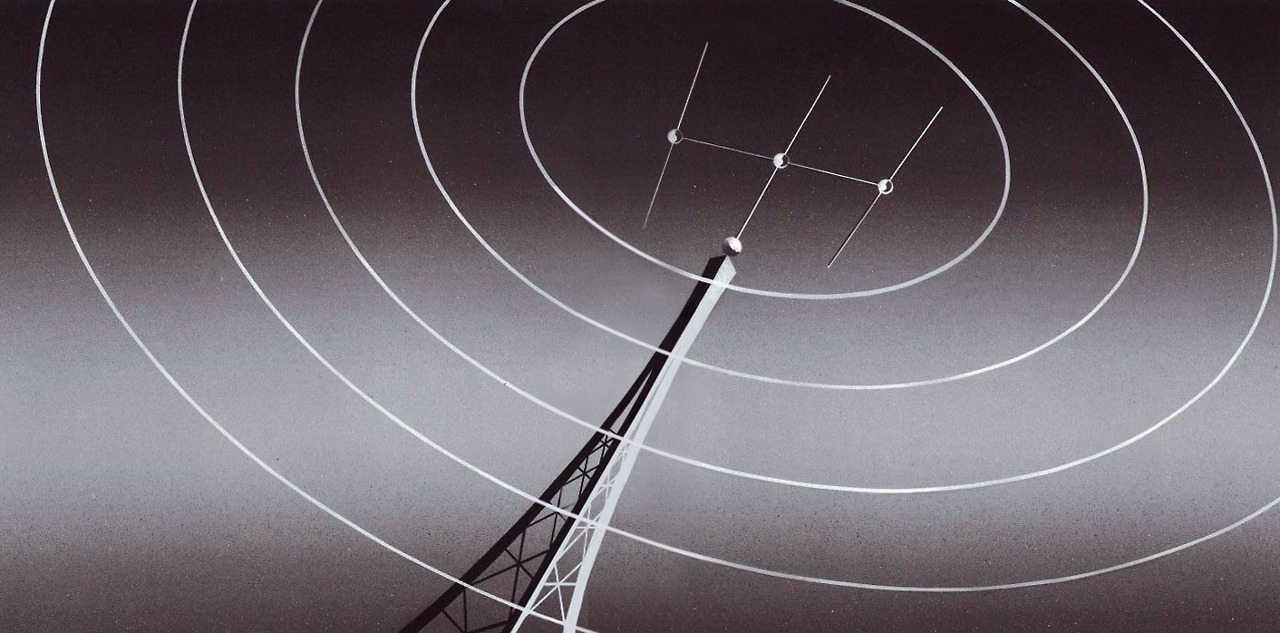

Radio itself, as well as being the primary channel through which rock ’n’ roll changed the world, is also at the very roots of electronic music, and this was well-known to Ralf and Florian. The first commercially available voltage controlled oscillators, electronic circuits that create the pure electronic waveforms that are the starting point for synthesisers were built as test equipment for radio stations. And the state-owned radio stations of Europe attracted composers and thinkers who started using the electronic sound generating equipment and tape recorders found in the studios to create a new kind of music. In 1951, the first electronic music studio, the Studio For Electronic Music (at WDR), was established in Cologne just a 30-minute train ride from Düsseldorf and it started broadcasting those strange sounds and noise across the nation.

“We grew up in a sort of crossroads between France and Germany,” Ralf told Melody Maker in 1974. “So we were exposed to the musique of Paris, as well as the electronic music of Cologne. That is what opened up our ears in the late 1950s.”

The broadcasting of the music being created by the likes of Herbert Eimert and Stockhausen in the Westdeutscher Rundfunk studio also had a political motivation, the music supported by the state as a kind of cultural bulwark of high art against the output of the communist East Germany, which was ideologically opposed to any sniff of elitist “difficult” music. It also served as a part of West Germany’s attempt to put some distance between it and the conservative and retrogressive cultural paralysis of the Nazi era. It was an activity Kraftwerk and many of their musical peers were actively engaged in, which was also encouraged by the state broadcaster – hence the unusual amount of German television and radio coverage of early experimental line-ups of Kraftwerk and other new groups of the late 1960s and 1970s.

Radio then was one of the drivers of technological change in the 20th century, the first mainstream and widely adopted communication device: “Travel / communication / entertainment…” as the computerised voice would intone on ‘Computer World’ six years later. Radio was the catalyst for electronic music itself. What could be a more perfect concept for Kraftwerk to explore?

Emil Schult remembers that once the new album’s concept had been settled, he and Ralf drove around Germany in the summer of 1975 in Ralf’s Volkswagen, the pair of them hunting down the right vintage radio set for the artwork. With recording underway, and a UK tour booked for the autumn, it was a busy summer.

Kling Klang was now home for Kraftwerk, an undistinguished semi-industrial unit rented on Mintropstrasse, Düsseldorf, below a unit occupied by an electrical installation company called Elektro Müller, whose sign still hangs above the entrance to the courtyard. Just a couple of minutes walk from the railway station, Kling Klang would become Kraftwerk’s own private sound creation world; part studio, part electronic workshop. It would gradually become hermetically sealed, impenetrable to outsiders and central to the Kraftwerk mythology. But in 1975, it was just Kraftwerk’s new home where they would start self-producing their albums. Conny Plank, the genius at the centre of so much of electronic music’s development in the 1970s and who had produced all of Kraftwerk’s albums up to this point, was jettisoned, paid off for his considerable contributions thus far, and work began in earnest on the new album without him.

According to Wolfgang Flür, the studio was sparsely equipped to begin with. “We were playful and clever enough to organise our work and technique for the upcoming themes,” he says. Ralf, Florian and Emil Schult worked initially on the melodies and arrangements for the album and then called in Karl Bartos and Wolfgang to add their parts. “The rhythms were easy and minimal, like before. They were quickly recorded on an eight-track tape machine that had been bought from the manager and producer of the German comedian Otto Waalkes.”

Work didn’t start before four in the afternoon, setting the leisurely pace of night-time recording, punctuated by regular breaks for visits to restaurants and cafés that would become the band’s habit for the next decade. Despite this slightly louche lifestyle, ‘Radio-Activity’ was recorded very quickly, in just a few weeks. “It was the fastest Kraftwerk album ever recorded,” says Wolfgang. His fondest memory of this period was the making of the infamous Kraftwerk drum cage. “It was built in the middle of the Kling Klang recording room. We thought that instead of drumming on our electric drum pad boards we should go into the future and develop something which did not need to be touched at all like with my brass sticks hitting on metal plates connected to electronic sounds of our Farfisa Rhythm 10.

“Florian bought some chromium metal rods from a exhibition display company. These rods had to be screwed together to make a human-sized cube so I could stand inside it. Screwed around the edges were photo cells that released three different drum sounds when my hand triggered the beam between those light cells. The drum sounds still came from the wire-connected drum machine. I drew this first draft of the cage on a paper napkin during a visit of us at the Fischerhaus Restaurant on the river Rhine in Düsseldorf during cake and coffee on the outside terrace in late summer 1975.”

Wolfgang singles out the track ‘Radioactivity’ as his favourite of the sessions. “Because of its theme and Ralf’s melancholic and monotone vocals. It was the first track where our Vako Orchestron was involved. I loved this instrument. It had cellophane discs with original recorded human chorus on, as well as violins and other instruments. Each instrument on one clear disc. The human chorus, these ‘ah’ and ‘oh’ voices inside ‘Radioactivity’, together with Ralph’s vocals give this song a melancholic vibe. That’s why I love it. My other favourite song is ‘Antenna’ because it has these electrifying, crunchy, rattling Minimoog tunes, with a poppy tempo and positive words. I always loved playing ‘Antenna’ live on stage. It attacks you with a strong and uplifting sensation!”

While Kraftwerk and EMI prepared to release ‘Radio-Activity’, the spurned Phillips/Vertigo label put together what they hoped would be a cash-in on Kraftwerk’s success – a double LP compilation of the first four albums they called ‘Exceller 8’. It boasted a peculiar and foreboding cover that seemed to be a kind of negative version of the original ‘Autobahn’ album cover. The sunny landscape was replaced by a dark, nocturnal scene, the road ahead leading into ominous storm clouds and mountains glowing eerily red, a distant pair of lonely headlights indicating a car coming towards the viewer. It didn’t do very well and soon ended up in record shop bargain bins and probably only served to confuse the marketplace for the release of the new Kling Klang Produkt proper.

Sure enough, when ‘Radio-Activity’ was released, it didn’t fare as well as had been hoped. It failed to chart in the UK and made it only to number 146 in the US charts. Wolfgang doesn’t remember any real disappointment in the Kraftwerk camp at the lack of success.

“We spoke about it, of course,” he says. “I think maybe the theme was too complicated. Perhaps it sounded too depressing for radio to play it often enough to reach the Top 10. It was not easy and lovely like ‘Autobahn’. The rhymes and words were putting forward complicated ideas, and it wasn’t what radio thought of as pop music. Anyway, I wasn’t involved in the authorship of it so it made no difference to me.”

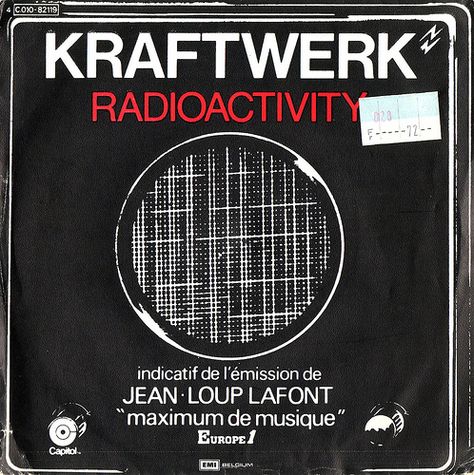

It was a different story in France where the album’s title track was used as the theme to a popular show on the Europe 1 radio station. Presented by Jean-Loup Lafont, ‘Miximum De Musique’ and was a big hit in 1976, as was the album.

“In France they have a different approach to entertaining music,” says Wolfgang. “I think it has to do with their traditional chanson music which the French are used to listening to, with its generally dramatic themes. ‘Radio-Activity’ was such a theme, with the melodies, its arrangement and Ralf’s unique vocals. The French seemingly loved it and this delivered us a Number One there.”

There was a neat thematic symmetry to that particular success and their acceptance into the chic Parisian music and art scenes would lend their next outing, 1977’s ’Trans-Europe Express’, a pan-European sophistication and appeal.

Kraftwerk wouldn’t have known it because the information wasn’t made public until 1989, but in December 1975, just a couple of months after the release of ‘Radio-Activity’, a nuclear power plant (or ‘Kernkraftwerk’) in the north of what was then East Germany, in Greifswald, came close to meltdown after a fire broke out. Had Kraftwerk known it they might have made the title song’s theme more explicitly anti-nuclear rather sooner than they did.

Now the album has been recast as an explicit anti-nuclear statement, and the title track is a staple of the endless Kraftwerk world tour, where the audiences are left in no doubt that nuclear power is a bad thing as far as Ralf Hütter is concerned. The version on the ‘Minimum-Maximum’ live album starts with a short but grim lecture on the dangers of nuclear waste and the above-mentioned litany of nuclear accident locations (more recently Fukushima has been added), with new lyrics about nuclear contamination. The song morphs into a dancefloor workout, the original melancholy mitigated by slammin’ beats.

As an artistic statement, ‘Radio-Activity’ was impressive. It was multi-layered and conceptual, its high art influences expressed though relatively accessible pop art. As a commercial entity it was a mixed bag. Reviews weren’t uniformly positive to say the least. A UK music press who met Kraftwerk’s initial breakthrough the year before with xenophobic headlines that referenced the war and Nazism in one way or another were primed for another ‘Autobahn’, but got something altogether more difficult to understand. The world (or at least the UK and the USA) it seemed still wasn’t quite ready for Kraftwerk.

The black and white ‘Goebbels schnauze’ radio artwork has since been usurped by the day-glo red and yellow radioactivity hazard symbol, the sound on the disc itself buffed up considerably from the original’s slightly under-produced Kling Klang origins (though the 2009 remaster is perhaps a tad over-compressed), the buzzing of badly earthed synthesisers has been (sort of) removed. The album’s glorious Beach Boys-y high point, ‘Airwaves’ has also been retooled live with a Moroder-esque ‘I Feel Love’ bassline, the sweet, naive vocal shrouded in vocoder, the whole thing engineered for the dancefloor. It’s not necessarily better these days, neither is it worse, but the fact is that ‘Radio-Activity’ has survived for 40 years as a crucial and fascinating part of Kraftwerk’s Gesamtkunstwerk.

Wolfgang Flür recalls a personal reaction to the ‘Radio-Activity’

“Some years ago I used to walk through our Hofgarten [city park] and one time I met an older friend of mine pushing his bicycle. On the back there was a young boy sitting in a basket, he was maybe three or four years old. I greeted my old friend and he introduced me to his little boy. ‘This is Elmond,’ he said, ‘and this is Wolfgang from Kraftwerk’. My friend explained to me that little Elmond had discovered ‘Radio-Activity’ and was listening to the music all day long. I asked Elmond why he liked the song. ‘Because you sing so sad inside,’ he said. My friend told me that his boy sometimes began cry during listening, which worried me. I explained to little Elmond that I was not the singer, but Ralf was. I asked him why he liked this sadness. After a few moments of thinking he replied: ‘Because it is beautiful,’ he said. I was flabbergasted! My friend explained: ‘Children make no difference between strong feelings like joy or sadness. Crying is also a strong feeling and they do unabashed what we adults have unlearned or have forbidden us in public. Stupid, aren’t we?’.”