First published in New Musical Express on 2 February 1980 under the title ‘The Emaciated Line Between Art And Ambience’, we’re heading into the eye of the Factory Records storm… or in Tony Wilson’s car on our way to meet The Durutti Column’s Vini Reilly

Tony Wilson, Granada TV producer and Factory Records major-domo, picks me up at Manchester Piccadilly for the drive out to Didsbury.

“The thing you have to remember about Vini Reilly is that the boy was very ill. He’s had this problem with the stomach… he suffers from bouts of anorexia nervosa where he can’t eat anything for months. Sometimes you have to talk to him before five o’clock because that’s when he eats. Afterwards he’s usually extremely sick.”

I look at my watch. It’s still only midday. Wilson continues, his customary brusquely cheerful self.

“Actually we had to make him step out of his illness to work on this Durutti Column album” – we being Wilson and his partner Alan Erasmus. “It was a risk. If you’d seen the boy you’d know. I thought, ‘That boy is either going to die or he’s got to get better’ and as people don’t age…”

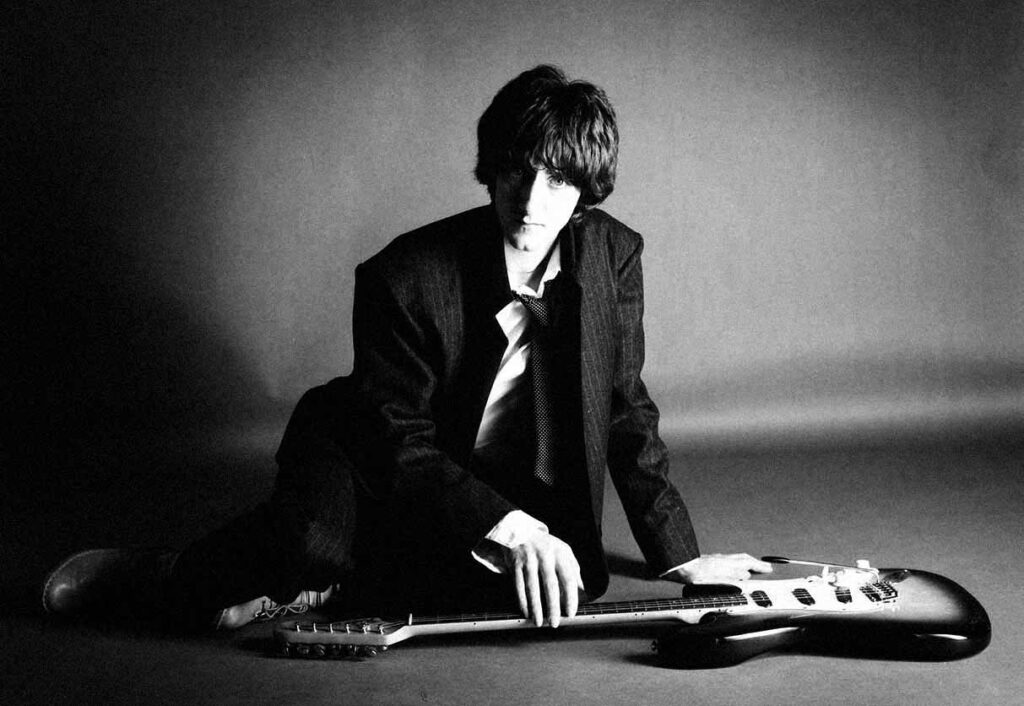

Opening the door on the terraced house where Reilly lives with his ma, we’re greeted by a small, frail figure with boney fingers. Reilly is in his mid-20 and is obviously extremely thin for his age. On the other hand he doesn’t look like he’s about to shuffle off this mortal coil.

Wilson accepts a late Christmas gift from Vini, a small charm, with much thanks and then disappears back to Granada where he does whatever producers do for TV programmes like ‘World In Action’. He is also finishing off the editing for a film constructed from an improvised jam with Reilly, keyboards player Steve Hopkins and bass player and general knob-twiddling wizard Martin “Zero” Hannett (shown on Granada’s ‘Celebration’ arts programme last week). These three are sometimes better known as The Invisible Girls, John Cooper Clarke’s back-up team on both ‘Sleepwalk’ and a forthcoming muse and music production which will be the wordman’s third long-player.

Reilly, by his own admission, is not at all well. For the last three years he’s suffered periodically from the psychological disease that stops him eating and the debilitating fits of depression that accompany this state. Now he seems relaxed and lucid, occasionally staring off into the corners of the room with an intense expression.

“The doctors can’t find anything wrong with me,” says Reilly softly. “All they do is give me tranquillisers and they make me go to sleep.”

The Durutti Column has been functioning on and off for as long as Vini has been sick, although it’s evident that working hard has been one way of staving off depression. The original Duruttis were a band with a part-time singer (Colin, an actor) who played melodic, newish wavish music with a bizarre swagger that now appears incredibly dated (witness their contributions to ‘A Factory Sample’ double EP, [FAC 2]).

Vini’s debut album, ‘The Return Of The Durutti Column’ [FACT 14], is quite unlike the Durutti Column of ‘A Factory Sample’. It’s mostly a solo guitar album, classically flavoured, tipping and modulating between themes with an appeal that haunts back to times past (childhood, personal reactions to the death of a parent, tune for lovers) and lightly structured sketches that have an electric flamenco propulsion. The music is Reilly’s own, occasionally assisted by bass and drums, but always translated through the able hands of Hannett.

“Martin reproduces echoes, finds a rhythmic pattern on the synthesiser. I gave him 20 tracks and he selected the ones he could work with best. I didn’t really hear the album from playing the pieces until the finished plastic.”

As the original Duruttis fragmented into lethargy and Reilly’s health lapsed, he had assumed that was the end of his musical career. But Wilson was adamant that he would work, and visited Reilly with a proposition for a solo album.

“I though they’d go on without me, but Tony said, ‘Look, you are The Durutti Column – now go ahead and do it’.”

Factory’s success with Joy Division has meant that the label can afford to nurture talents like Reilly’s or A Certain Ratio’s without hurrying them into unnecessary deadlines.

“They have a lot of schemes now. There’s an idea for a fun film, ‘Too Young To Know, Too Wild To Care’, which I’m scoring.”

Reilly confesses that he was terrified of being boring on his record and thinks that some people will buy it for the wrong reasons, either because they collect Factory artefacts regardless, or because it’s got a sandpaper sleeve.

“The music is incredibly simple, but I’d like anyone to listen to it and enjoy it, to get something out of it. It doesn’t hit you, it’s the kind of thing that takes time to sink in. What I really like is when aunties and uncles hear it and you see them tap a foot, or when a friend says they went to the pub and came home and got stoned and put it on. That’s what it’s for.”

Reilly gently resents some claims that the record is ambient, or that it’s a less imaginative version of an ECM album; cerebral music for washing up.

“That’s an insult. I could have been mathematical about it all, but every piece has a raison d’etre, an inspiration. Some people, rock critics I suppose, listen to music in a false situation. I like Keith Jarrett, but I think all other ECM music is crap.”

Steve Reich?

“Incredibly boring. You begin to suspect people’s motives for liking that kind of thing. The whole elitist thing in music is desperately wrong. Truthfully, I don’t know why anyone would want to listen to my record, because I made it to interest myself, but I do think music should have a place in society. It isn’t fair that opera can get Arts Council grants – though I have nothing against opera – when rock music, which is equally as important as an art form, is considered a lesser form of expression.”

To my surprise, Reilly says that he likes to meet up with some friends “to thrash about with rock and roll, ‘Jumping Jack Flash’ and ‘Johnny B Goode’.”

It’s obvious that he’s happiest with a guitar in his hand. Reilly practices constantly, using a piano for ideas and studying composition from records and books. He’s as interested in Benjamin Britten as he is in Ry Cooder, but in the words the old Ed Banger And The Nosebleeds song which Vini co-wrote with Mr Banger while guitaring for that combo, he ‘Ain’t Been To No Music School’.

Vini is anxious to play live again. He misses the honest reactions of a club audience.

“I started off playing sort of jazz rock with The Wild Rams, but with the Nosebleeds, Ed would get a real response jumping across tables and confronting the people. Then I was asked to play on ‘TOTP’ with Jilted John, but I don’t respect anybody involved in that.

“With John Cooper Clarke I don’t know what will happen. He’s been greatly misrepresented. People pick up on the swearing, but there’s a lot of very sad stuff too.”

As the afternoon sinks in, we walk over to Hannett’s house in a smarter part of Didsbury. The rest of the day is spent at Cargo Studios in Rochdale where Hannett is mixing A Certain Ratio’s contribution to the ‘Science Fiction Festival’ album. It’s good to see such an informally mischievous person with such supple rolling fingers behind a desk. In the studio Zero can go totally indulgently insane.

But that’s another story. Vini Reilly didn’t come to Rochdale anyway. He had to go and collect his dole.

“It gets a bit difficult to tell them you can’t come on a certain day because you’re doing a television programme. ‘You, on television?’, I get funny looks; I don’t want to be on the dole much longer. If these things all work out maybe I can earn enough to live without all that.

“The great thing about Factory – I want you to put this in – is that they never gave up on me.”

And then he adds, maybe as an afterthought…

“Factory can seem very serious. It gets taken very seriously. Really though it’s just like a very good game.”

Accentuate a very good game. It isn’t played to lose.