The irresistible draw of robot imagery and the idea of the Man-Machine is one that is firmly embedded in popular culture…

When Kraftwerk first trundled out their robot versions of themselves, they excited a range of emotions ranging from derision to disquiet, as well as affection and awe. As is often the case with Kraftwerk they seemed to be inviting laughter at their own expense – zer funny, mechanical little Germans – yet were themselves having the ultimate, prophetic last laugh. Both their sense of humour and their high seriousness were, still are, underestimated by their critics.

Kraftwerk’s robots are the most famous in pop history, and the most meaningful. More than self-deprecating gimmick, they were meant to excite a response and provoke reflections on the relationship between man and machinery, which in the often fearfully Luddite world of pop and rock has often been a fraught one.

When ‘The Man-Machine’ was released in 1978, the idea of music created wholly by synthesisers was a deeply alarming prospect, and not just to rock purists who considered synthpop fey and effeminate (Kraftwerk’s posing and pouting on ‘The Man-Machine’ album cover was both an allusion to the Constructivist art movement and also to taunt those 70s rockers easily offended by goddamn lipstick wearing Kraut “faggots”). It was also of great concern to the Musicians’ Union who were understandably angered at the idea of their members being put out of work by the arrival of sequencers heralded by Donna Summer’s ‘I Feel Love’, which spelt ruin for the pop orchestra. There was also a wider concern, felt in Kraftwerk’s native Germany and across the capitalist West about the increasing use of automation in the car industry and what this would mean for the human labour force.

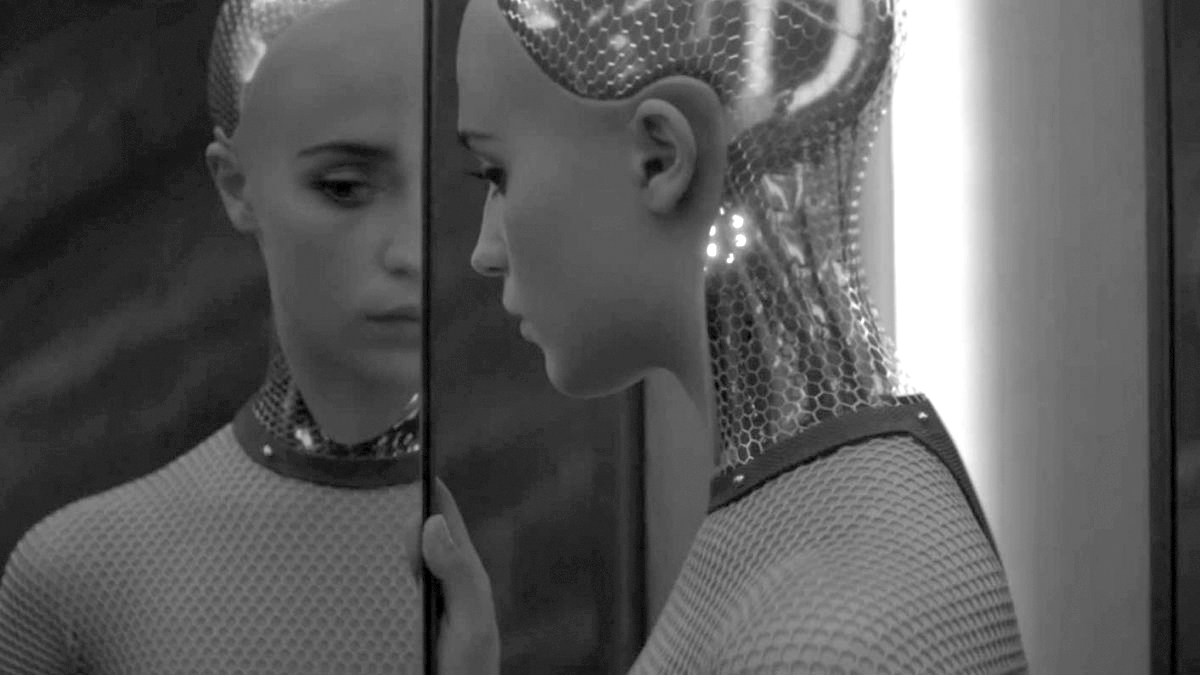

At a deeper, more psychic level, Kraftwerk’s replicas, although as close to ventriloquist’s dummies as robots in appearance, reminded of the folkloric German tradition of the “doppelgänger”, the double or evil twin of a person who, as in Edgar Allen Poe’s short story ‘William Wilson’, harboured the intention of displacing the “real” person.

For Kraftwerk, however, not only did their robot creations challenge taboos about what was authentic and inauthentic in pop, but they served as a way of distracting attention from their own, private selves – previously, on songs like “Showroom Dummies” and “Hall Of Mirrors” they had reflected on the idea of the celebrity as spectacle, as victim of the public gaze. Kraftwerk projected their “selves” as part of an immaculately conceived pop concept, as symbolised by the robots. They recoiled at the idea of pop as messy autobiography or soap opera – creating themselves as artificial icons was a way of guarding their privacy.

The robot, the mechanical music player, had a long history prior to Kraftwerk, stretching right back to the 18th century. Jacques de Vaucanson (1709-82) was not only famous for creating a mechanical quacking duck which delighted theatre goers in 1738, but also a mechanical flute and tabor player. In 1773, Henri-Louis Jaquet-Droz presented for exhibition a doll-like female mechanically playing the piano followed by a mechanical bow.

The concept of the “robot”, however, was not coined until 1920, when the Czech playwright Karel Čapek’s Rossum’s Universal Robots. The word “robot” is derived from “rabotnik”, the Russian word for “worker”, and from the outset, the robot was a cipher for anxiety about the location of the human soul and whether robots might use their uncanny and extra-human potential to rise up against their masters. Čapek was an influence on Fritz Lang’s ‘Metropolis’, actually a rather garbled proto-Nazi parable, but also featuring the “Maschinemensch” robot, a concept revisited by, among others, American singer Janelle Monae in her 2007 ‘Metropolis’ suite, in which the ‘Metropolis’ throwback android Cindi Mayweather is clearly a metaphor for racism; prejudices are faced by “wired folk” on the grounds that “we have no feelings no memories or minds”. The theme of robot emancipation, a perennial anxiety of popular culture equating to black emancipation is implied also in Chris Alfaro’s hip hop project ‘Free The Robots’. Certainly, there is a particular identification among African-American audiences for all things electronic, robotic and stiffly Kraftwerkian from the 1970s onwards – the stiff, uncanny movements of bodypopping being just one example.

As well as being sinister portents for the future destruction of humanity, however, from the 1950s onwards, when they were popularised in science fiction movies and TV series, robots became creatures attracting affection rather than fear; cute, metallic cuddly toys. One novelty upshot of this was Les Robots-Music, introduced in 1958 by Edouard Diomgar who conceived the idea of a robot trio playing traditional instruments while in a German prisoner of war camp. Featuring Oskar on accordion, Ernest on saxophone and Anatole on the drums, this metallic/pneumatic trio released a series of albums, on which they performed selections from their repertoire of 500 songs, including a version of The Village People’s ‘YMCA’ and continued to tour right through until the mid-1980s.

Other music world robots of note include ‘Mr Roboto’, created by Dennis DeYoung, a song featuring on the 1983 Styx rock opera ‘Kilroy Was Here’. The opera reveals a lot of the rock community’s anxiety about the impending synthesiser age – it stars DeYoung as Kilroy, imprisoned in a futuristic institution for “rock ’n’ roll misfits” guarded by the “Robotos”, one of whom (Kilroy) overpowers and assumes its metal shell to make good his escape. The song is awash with vocoders and Oberheim and PPG Wave synthesisers to signify this imaginary oppression.

Despite present-day anxieties about AI, the pop robot is very much a retro-futuristic proposition, most popularly expounded by Daft Punk, writers of ‘Robot Rock’, whose extensive use of vocoders and perma-helmets seems to refer back to the late 20th century rather than the 21st or 22nd. Their genre could be seen as an immaculate, gently ironic enhancement of pop, rock and funk in the eras when it self-consciously grappled with new machinery. However, as with Kraftwerk, their helmets also conspicuously and conveniently preserve the anonymity of these two superstars, enabling them to go about their days untroubled by paparazzi or autograph hunters.

In subsuming their humanity with the robot masks, they have created for themselves true doppelgängers, a feat even Ralf Hütter couldn’t manage.