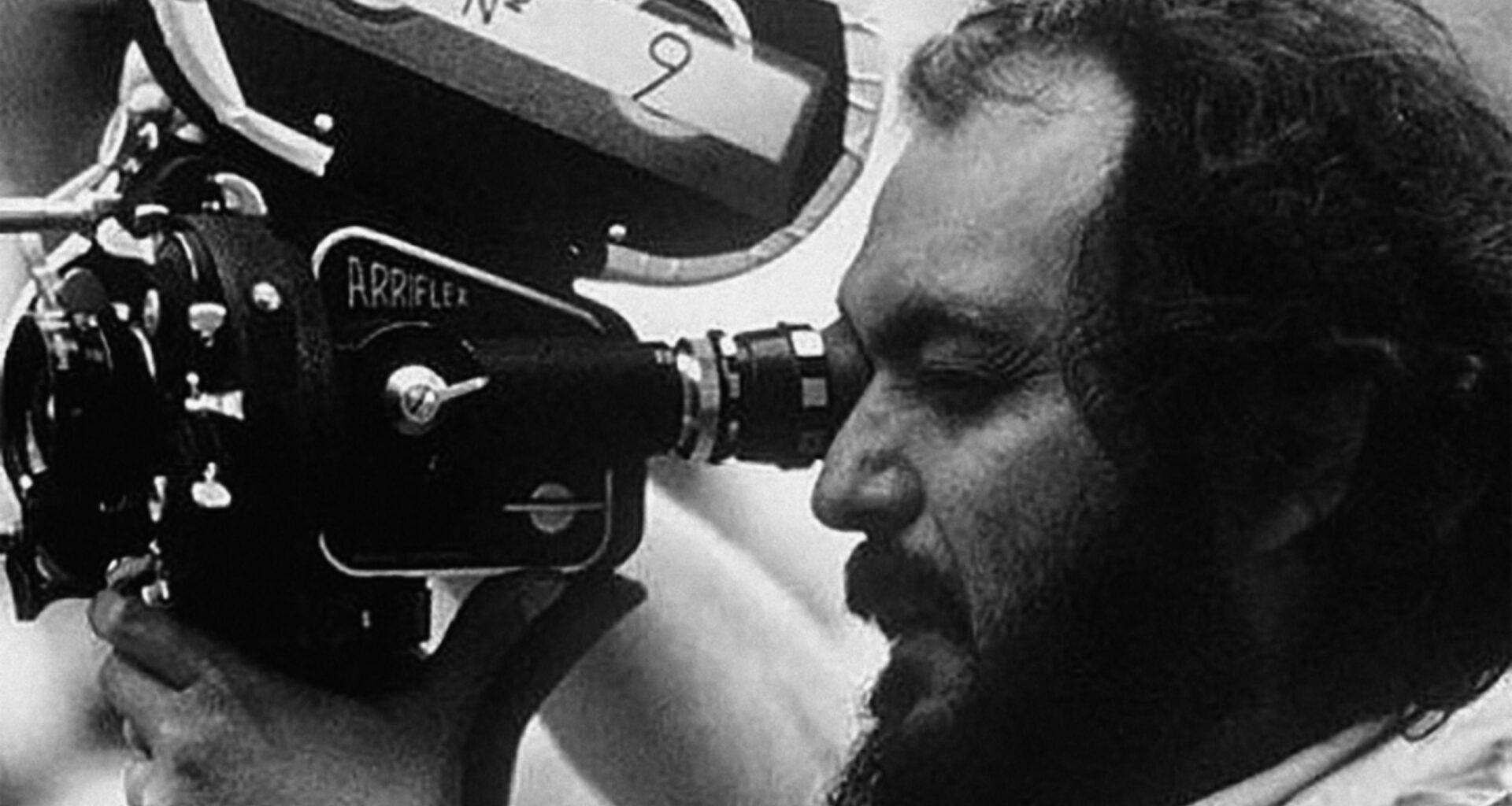

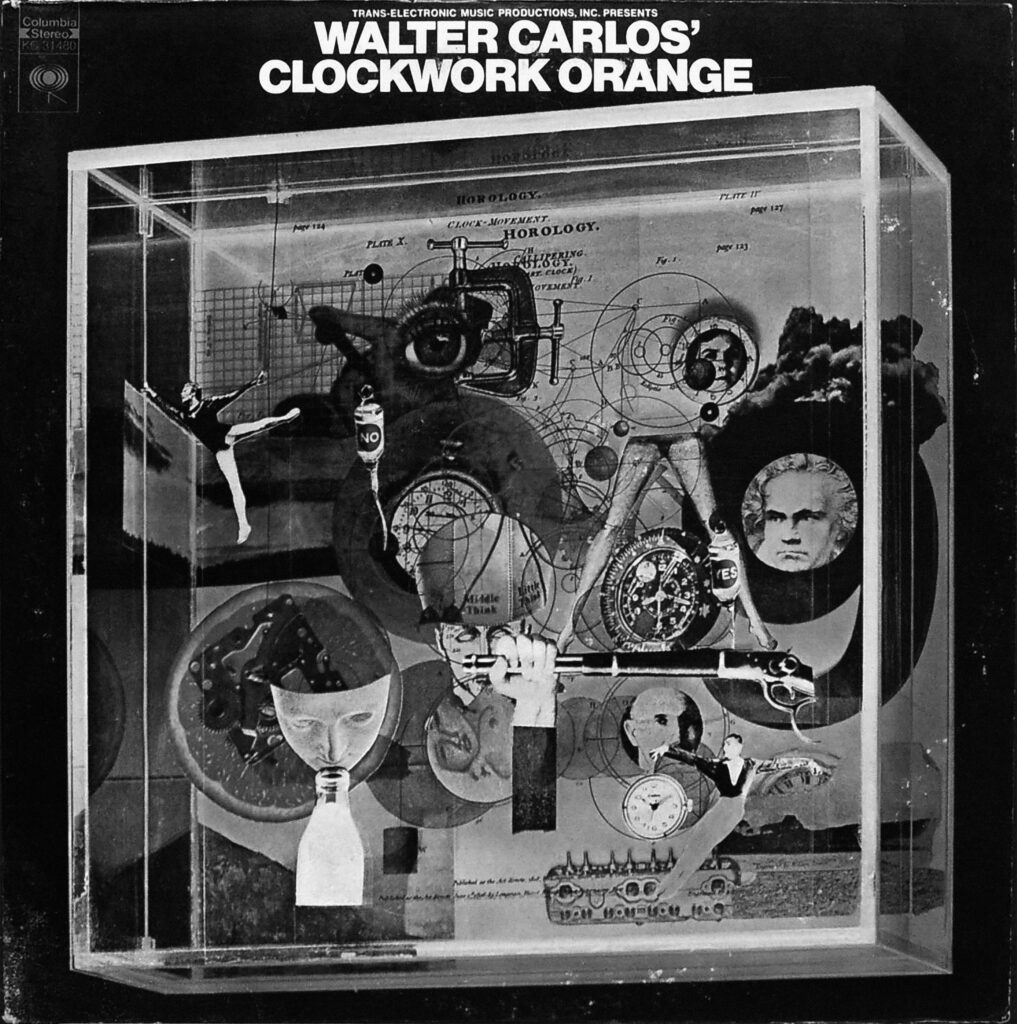

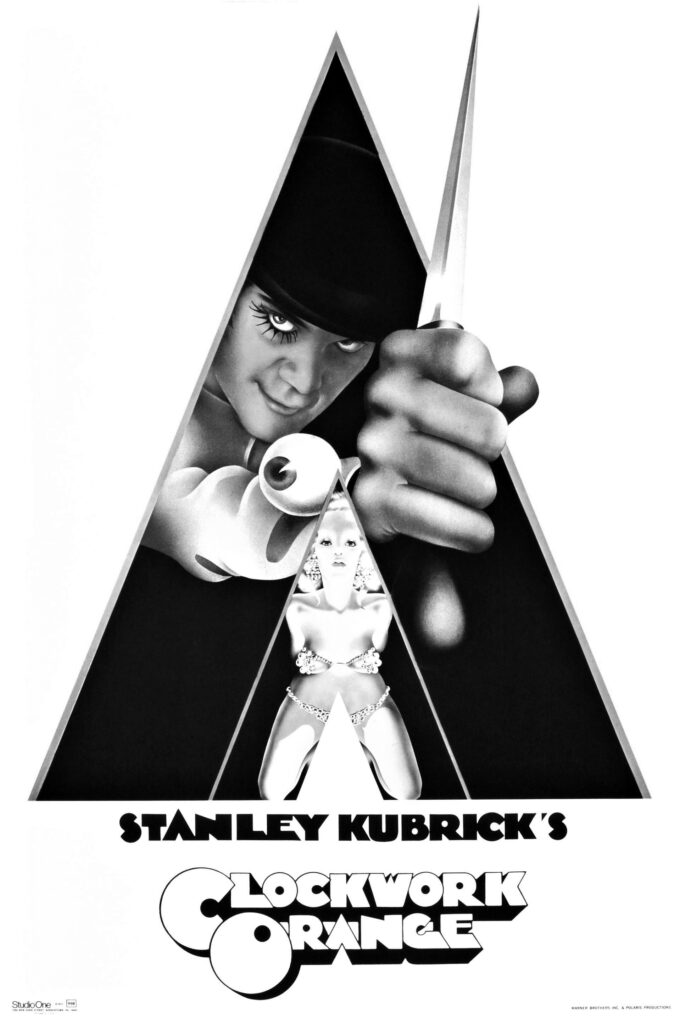

Wendy Carlos’ pioneering soundtrack to Stanley Kubrick’s ‘A Clockwork Orange’ was just as subversive as the film, debasing classical masterpieces and putting electronic music on the map. We delve into the work of the maverick musician, the singular director, and their turbulent working relationship…

“WENDY!” bellows Jack Nicholson’s character Jack Torrance as he monsters his wife on the stairs of the Overlook Hotel in Stanley Kubrick’s 1980 film, ‘The Shining’. Wendy, played with heart-stopping terror by Shelley Duvall, swings a baseball bat at him with her thin arms and whimpers “Get away from me!’, before finally making contact and sending her gruesome psychopathic husband tumbling down the stairs to a date with a headache in a refrigerated store room.

It is, of course, a coincidence that Wendy Torrance shares her name with the soundtrack composer so readily associated with Stanley Kubrick, but maybe when Wendy Carlos first watched the finished film with her producer/co-composer Rachel Elkind, she may have related to her namesake’s suffering, and perhaps she might have liked to have wielded a baseball bat at Kubrick herself.

Why? Well, this is Stanley Kubrick we’re talking about. Carlos and Elkind laboured on an electronic score for the film for months, producing four hours of music in the process. Kubrick, true to form when hiring composers for his films, used hardly any of it.

“My experience wasn’t a very happy one I’m afraid,” Elkind told TV Store Online in 2014. “I stopped working after ‘The Shining’.”

Elkind’s problem, she said, was with the film itself, of watching images of horror over and over again while composing, and the negative effect it had on her and, she suspected, on audiences. But you can’t help wondering whether it was more down to the ruinous work practices she had to stomach.

They sent acetates of the music they were making to Kubrick as he was shooting the film. The feedback from the backers, Warners, was that the music was very scary. Indeed, the chilling opening sequence was powered by Wendy and Rachel’s ominous synthesiser notes, at funereal pace, accented by bells, shrieks and bursts of hissing white noise. It was terrifying. But that was almost all that was used. ‘The Shining’ was the second and last time they worked with Kubrick.

It was Kubrick’s ‘A Clockwork Orange’, released nine years before ‘The Shining’ in 1971, which started the ball rolling. Wendy Carlos had studied music composition at Columbia University. She was among the students of mid-century electronic music titan Vladimir Ussachevsky, and had worked with him at the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center in New York, home of the infamous RCA Mark II Sound Synthesiser, aka The Victor.

In the mid-1960s, when Robert Moog was developing his synthesiser modules, he went to Princeton seeking input from the experts. Ussachevsky advised Moog to develop the ADSR filter, a concept at the heart of synthesis ever since. Carlos, who didn’t get along with the austere, alienating world of academic electronic music, soon became Bob Moog’s first customer, and would present him with suggestions as to what his synthesiser modules should be capable of in order to become essential compositional tools for musicians.

Carlos was able to trade musical skill and technical input for equipment, and one of the first tangible fruits of that arrangement was Moog’s initial demonstration disc, a 10-inch mono promo that featured Wendy putting the Moog 900 Series through its paces. Carlos’ skill with the Moog system led to the release of the 1968 smash ‘Switched-On Bach’. Against expectations, the record sold a million copies, and put Carlos, Moog and electronic music on the map.

She followed up this success with 1969’s ‘The Well-Tempered Synthesizer’ and started working on a fresh composition, ‘Timesteps’, designed to introduce a new piece of kit: a spectrum follower, which turned the human voice into an electronic signal. Carlos had already used it to create a machine version of the choral movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, and was working on ’Timesteps’ when she started to read Anthony Burgess’ ‘A Clockwork Orange’. She felt the music she was making suited the book’s dystopia perfectly, and so the piece took on an influence from the novel. She described it as an “autonomous composition with an uncanny affinity for ‘Clockwork’”.

When Carlos heard that Kubrick was making a film of the novel, she and Rachel sent him the Beethoven piece and ‘Timesteps’. The last-minute scramble to have Carlos’ music on the soundtrack paid off, and the film’s title theme, a synthesised version of Purcell’s 1695 piece ‘Music For The Funeral Of Queen Mary’, helped make one of the most iconic opening scenes in film history.

The movie’s notoriety gave the whole undertaking a counterculture cachet. The stylised violence, a compellingly brilliant performance by Malcolm McDowell, the set, costume design and language, all created an aura that was only enhanced by the repugnance with which it was received by some critics. The electronic music tipped the whole experience over the edge.

Carlos’ soundtrack provided some of her trademark Moog-mangled classics. This time, however, in contrast to the sprightly and virtuoso jaunts through the baroque of ‘Switched-On Bach’ and ‘The Well-Tempered Synthesizer’, the mood was decidedly dark. The discordant synthesiser note at the start of her version of ‘The Funeral Of Queen Mary’ reverberated through electronic music ever after, and created a sense of dread entirely suited to Kubrick’s shocking and unforgettable imagery.

The machine-generated tones themselves provided a futuristic feel, but also served to distort and contaminate the original, debasing it. The second and fourth movements of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony came in for the same treatment. If anything, Carlos’ versions are even more extreme than the shocking Purcell revision. It’s an almost punk approach in its disregard for the norms and niceties of classical music, and ‘A Clockwork Orange’ prefigured punk’s cartoonish violence and nihilistic rejection of society’s rules.

Carlos’ adaptation of classical music was as offensive to some aficionados as Johnny Rotten would be to the established order. The wilful sonic thuggery meted out on Gioachino Rossini’s ‘William Tell Overture’, which mechanically gallops along like one of Ligeti’s barrel organ pieces, cut to a speeded-up sex scene, and the sheer thrilling modernity of the synthesiser (not to mention the kick-ass tunes of Purcell and Ludwig Van) appealed to the film’s youthful fanbase, including David Bowie who later cited the film’s costumes and dystopian vision as an influence on his Ziggy Stardust phase. He even used an excerpt of Carlos’ electronic Beethoven music to open Ziggy shows in 1972 to drive the point home.

But it was ‘Timesteps’ in particular, used by Kubrick for the briefest moment as Alex is strapped in to his seat to receive the Ludovico technique treatment, which fixed Carlos and ‘A Clockwork Orange’ as essential building blocks of modern electronic music.

This abstract piece was scarcely noticed in the film, and was quickly replaced by synthesised Beethoven over images of the Third Reich in full pomp and other horrors, but the soundtrack album featured over five minutes of it. Synthesisers whine and the piece builds to a frantic pace, a racing rhythm of white noise and mad tootles that gives way to artificial explosions, clocks ticking and disembodied robotic voices, before it climaxes with a thunderous chord. The effect is powerfully unsettling.

For Kubrick’s part, he seemed to be saying that a taste for high culture was no guarantee of human decency. After all, as the director pointed out quite explicitly, Hitler liked Beethoven too. But the composer was weaponised in the film: Alex gets clobbered with a bust of Beethoven during a burglary, and its inclusion on the soundtrack of the films he’s forced to watch make it impossible for him to listen to the music again without wanting to die. When Alex does make a suicide attempt, it’s because his saviours/captors pipe the pieces at high volume into his room.

After ‘A Clockwork Orange’, Carlos released several more albums of electronic, well-known classical works, before reuniting with Kubrick for ‘The Shining’ in the late 1970s. ‘The Shining’ soundtrack has been out of print since its first vinyl pressing, and there is no official CD release, although the two CD volumes of ‘Rediscovering Lost Scores’, released by the US label East Side Digital in 2005, feature much of the music she composed for it.

Those compilations gather together around 35 cues Carlos wrote for the film, but according to Gordon Stainforth, the film’s music editor, only the opening title from the original work remain unmolested in the final cut. Instead, encouraged by Kubrick, Stainforth ended up layering different pieces by Polish composer Krzysztof Penderecki on top of each other, an almost sacrilegious approach that the director said no one would notice. He did the same with Carlos’ music, “sandwiching” two or more of her cues together.

Wendy Carlos will forever be identified with ‘A Clockwork Orange’ and the dark electronic magic she conjured up for it. She keeps going back to it, like an itch she can’t scratch. Her last release of new material, the 1998 album ‘Tales Of Heaven And Hell’, included a major piece, ‘Clockwork Black’, “a brooding, dark return to the land of ‘A Clockwork Orange’” as she put it in the sleeve notes. “I wanted to reach for the underbelly of moods that were implied in the original film, but exposed in all their horror for the present,” she concluded.

That was 20 years ago, written about music composed nearly 30 years before that, but the music she made back then remains unsettling and timeless.