In 1989, Finitribe landed themselves in hot water with a provocative campaign to promote their ‘Animal Farm’ EP. Frontman Davie Miller relives the day the corporate lawyers came a-knocking

Edinburgh’s Finitribe, who started out as a John Peel-endorsed post-punk outfit running their own Finiflex label from Leith, found themselves right at the centre of the acid house storm when their 1988 12-inch ‘De Testimony’ was picked up by DJs such as Paul Oakenfold. It was helped along by its inclusion on the wilfully eclectic ‘Balearic Beats – The Album Vol 1’ sampler. And yet there was never anything especially “chilled out” about Finitribe, as evidenced by the shenanigans which surrounded the release of their ‘Animal Farm’ EP the following year.

‘Animal Farm’ is a polemical cover version of ‘Old MacDonald’, complete with stuttering Foghorn Leghorn samples, crazed chicken squawks and horse whinnies, stabs of doom-laden piano, a dirty bassline and a relentless bosh-bosh beat. Over the top of all this, Davie Miller sneers a foreboding Trent Reznor-style rap diatribe about “international corporate death burgers” and “blood red gold” leaving you in little doubt about the band’s attitude towards the famous fast food outlet.

“All our records at that time were very tongue in cheek,” explains Davie. “We used lots of cartoon samples so there’s a certain amount of humour in them. ‘Animal Farm’ was about anti-consumerism and big corporations. The anti-McDonald’s sentiment was a big thing back then, because of the way they farmed animals in South America and how they treated their staff.”

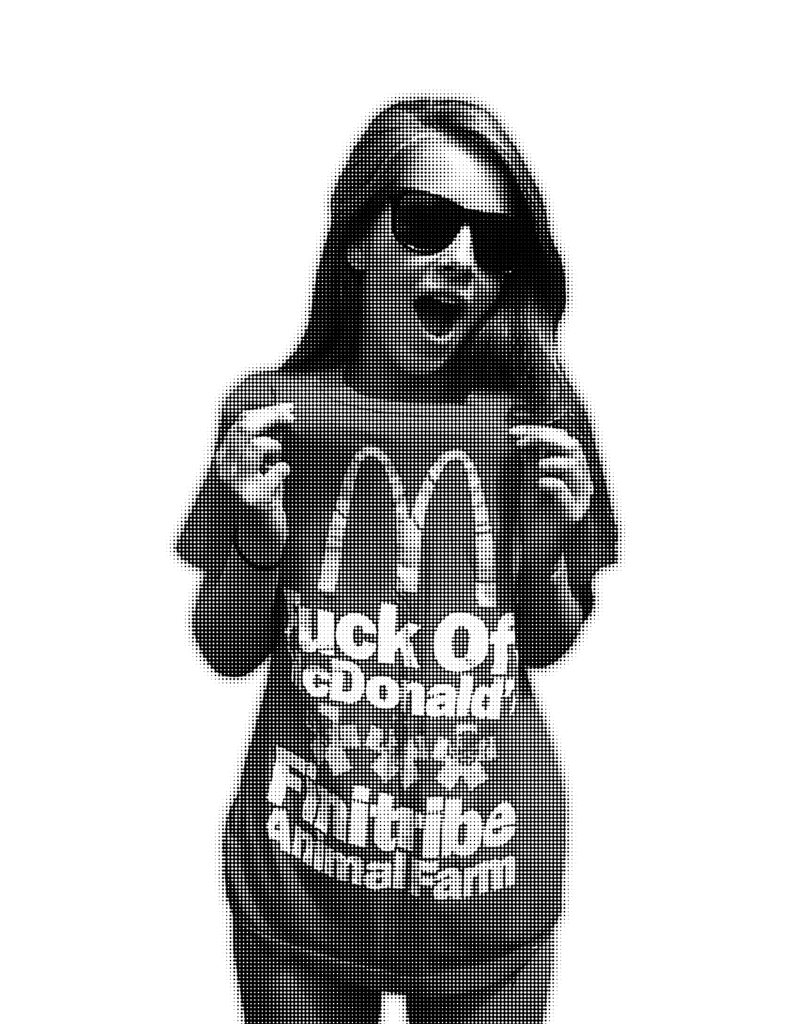

Having just signed to the anarcho-leaning One Little Indian label, the band hatched a bold marketing plan with label boss Derek Birkett that was almost guaranteed to garner immediate attention. They designed posters and T-shirts bearing the brazen slogan “Fuck Off McDonald’s” using the same typeface as the burger chain, and featuring their famous golden arches logo.

“We came up with the idea fairly quickly in collaboration with Derek, at the very first promotional meeting about the record,” says Davie. “It was all done very quickly. We just jumped in his Range Rover, drove all over London and put the posters up ourselves. It created a pretty immediate reaction, because of the likeness to the logo it makes you look twice.”

Needless to say, when you pull a stunt that infringes the copyright of one of the world’s biggest corporations, you stand a pretty good chance of attracting their attention.

“McDonald’s lawyers were on the phone within a day,” says Davie, “I don’t even think they heard the track, it was the posters that got us on their radar.”

Was there any nervousness in the band about fallout from this feisty guerrilla campaign?

“We were all really excited about the idea,” he says. “It was great to see the posters going up and witness the reaction to them, they were incredibly popular. It did cause a stir in the press and people started coming to our gigs because of it, particularly protesters and people interested in music with a political stance. I remember one gig at Manchester Boardwalk, we played with Chumbawamba, attracting a lot of travellers. Someone actually brought a horse to the show, it came up the stairs and into the venue. There’s a story that a McDonald’s worker wore one of our T-shirts to work and was sacked immediately, but I don’t know if it’s true.”

Did signing to One Little Indian, a label that besides siring a few surprise hits like The Sugarcubes was largely focussed on releasing uncompromising work, change the way they approached the business of releasing and promoting records?

“We were already fairly political at that point,” says Davie, “but One Little Indian became a very supportive home for us, because of course Derek himself was highly politicised having been in Flux Of Pink Indians and involved in activism. Being on his label just felt right and we were encouraged. It was a great creative environment to work in, initially at least. We actually did it mostly out of mischief and fun more than anything.

We liked to provoke people through our songs of course, but we weren’t really all that tubthumping.”

Presumably the offending items have become sought after collectors’ items by now?

“I’ve seen them go a for a few hundred quid on eBay,” marvels Davie. “A friend did a remix for us recently and I promised him a poster to repay the favour. It’s one of only two I’m aware of that still exist. I posted it off to him in America and bizarrely enough it arrived back at my house the other day, so who knows if someone opened it up first and intervened.”

Maybe the forces that be are determined to weed out such subversive propaganda sent from the shores of sunny Scotland.

“The funny thing is everyone assumed we were all staunch vegetarians or some really radical hunt saboteurs, but we weren’t,” laughs Davie. “John [Vick] was the only vegetarian in the band. We just saw it as an exciting, antagonistic thing to do. I’m quite proud of it. I’d have one of the posters up on my wall, but it’s quite a brash statement. You’d need a massive fuck off house to carry it off!”