‘The Future Of Music: Credo’.

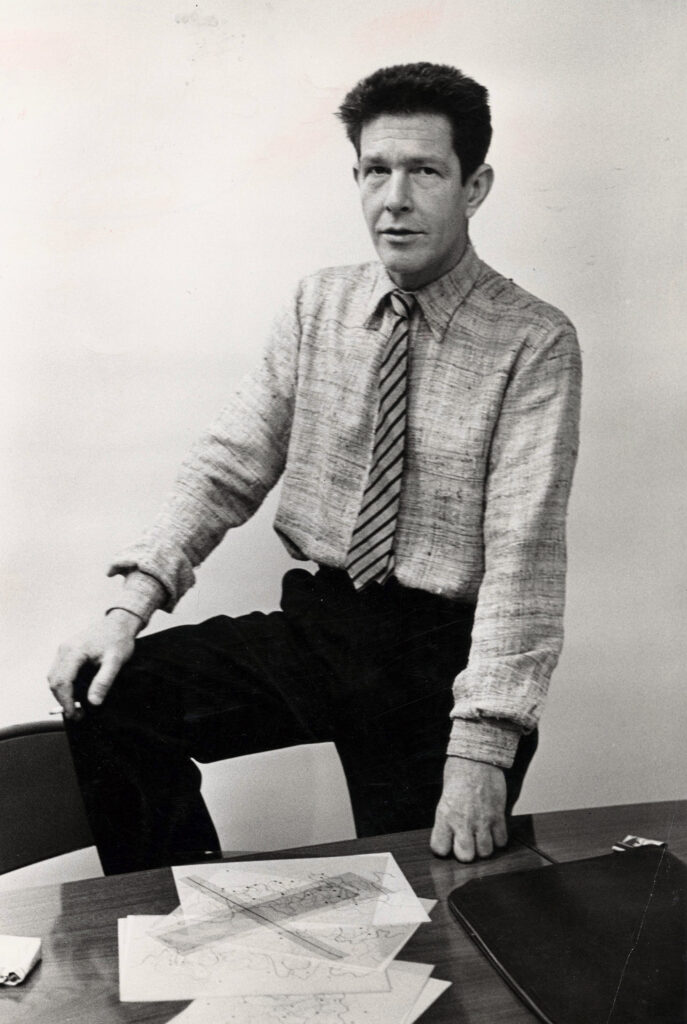

In 1937, Laurel and Hardy released ‘Way Out West’, Irmin Schmidt of Can was born, the coronation of George VI took place, the first jet engine was tested in England, Daffy Duck made his cartoon debut, the Hindenburg disaster acted as a foretaste for greater conflagrations to come, and a memorial concert to George Gershwin was held at the Hollywood Bowl, its sound so immaculate that it could be released on CD decades later with barely a tweak. That same year, a young and impecunious music and art theorist called John Cage delivered a lecture in Seattle titled ‘The Future Of Music: Credo’.

With its dual, concurrent text of upper and lower case, this was a highly modernist work, the stuff of which the general public of his day had barely thought to dream. “I BELIEVE THAT THE USE OF NOISE TO MAKE MUSIC WILL CONTINUE AND INCREASE UNTIL WE REACH A MUSIC PRODUCED THROUGH THE AID OF ELECTRICAL INSTRUMENTS,” declared Cage. Such instruments existed after a fashion, he conceded, but they were used in too sentimental and nostalgic ways – the theremin, for instance. “Thereministes did their utmost to make the instrument sound like some old instrument, giving it a sickeningly sweet vibrato, and performing upon it, with difficulty, masterpieces from the past,” he said.

Cage’s gaze was set futureward, but his prognostications were based on what was already technically feasible. “It is now possible for composers to make music directly, without the assistance of intermediary performers,” he declared. He foresaw percussion as playing a starring role in future music, perhaps inspired by pieces such as Edgard Varèse’s ‘Ionisation’. “Percussion music is a contemporary transition from keyboard influenced music to the all-sound music of the future… the means will exist for group improvisations of unwritten but culturally important music. This has already taken place in Oriental cultures and in hot jazz.” Finally, he envisaged the rise of centres dedicated to the performance of electronic music, in which “oscillators, generators, means for amplifying small sounds, film phonographs, etc” would be available to modern-minded composers.

All of this was highly prescient; before the outbreak of World War Two, Cage would be making music using gramophone players, making him arguably the first “turntablist”. He had also alighted on the idea of using everyday objects as a means of producing musical sounds, a commonplace concept today but in the 1930s quite radical in its proposal that the walls between art and life should be collapsed. This was essentially the principle of his most famous piece, ‘4’33”’. The aim is not to present silence, but rather the absence of performed music in which the inevitable sounds of the environment become the musical content.

In many ways, however, Cage’s text is a throwback to one written almost a quarter of a century earlier – Luigi Russolo’s ‘The Art Of Noises’ manifesto, penned in 1913, in which the Italian Futurist declared that “with the invention of the machine, noise was born” and that in the early 20th century “we find far more enjoyment in the combination of the noises of trams, backfiring motors, carriages and bawling crowds than in rehearing, for example, the ‘Eroica’ or the ‘Pastoral’”. Cage echoes these sentiments. “Wherever we are, what we hear is mostly noise,” he said. “When we ignore it, it disturbs us. When we listen to it, we find it fascinating. The sound of a truck at 50 mph. Static between the stations. Rain.”

Furthermore, Russolo had attempted to back up his words with inventions, to wit the large, cumbersome “intonarumori” or noise intonators he devised. Using handles, these emitted a series of primitive sounds, one per machine, which were beyond the range of conventional instruments. Russolo doubtless optimistically imagined that society would quickly fall in with Futurist ways, but the development of electronic instruments stalled, so that come the late 1930s when Cage wrote his manifesto, composers like himself and Varèse were still waiting for the technology to be invented that would match their musical ambitions.

This only occurred more than a decade later, after the war, with the rise of pure electronic music studios in Cologne, inhabited by composers like Stockhausen and Eimert, while the availablity of magnetic tape gave rise to musique concrete, as practised in France by the Pierres Schaeffer and Henry – the means whereby, soundwise, we were on our way to being able to make anything out of anything. The timeline ahead was clear. By the time Cage’s lecture was eventually published, in 1958, Varèse was presenting his masterly ‘Poeme Electronique’, Stockhausen and Ligeti had already added to a growing oeuvre of electronic masterpieces, while the efforts of Joe Meek, Delia Derbyshire and others would see electronic music insinuate itself into the pop mainstream.

John Cage himself went a slightly different way. Although serious about his work, he was a cheery personality who did much to popularise new ideas of music as a form, appearing on American TV to demonstrate his set pieces involving domestic objects, laughing along with audiences, introducing chance as a key factor in composition, and working in tandem with parallel-minded artists like Robert Rauschenberg. In 1937, he had accurately foreseen the future as it would generally pan out, but it was one that only partly intersected with his own.