The theme to BBC children’s show ‘Blue Peter’ is instantly recognisable, but did you know the version used from 1979 to 1989 was recorded by prog godhead Mike Oldfield?

Composed by Herbert Ashworth-Hope in the 1930s, the ‘Blue Peter’ theme is a sea shanty, or hornpipe to give it the correct name, called ‘Barnacle Bill’. The version by Sidney Torch & The New Century Orchestra opened the famous children’s show since its inception in 1958. No wonder that some 20 years down the line the powers that be decided that it was, perhaps, time for an update.

Enlisting the talents of Mike Oldfield to record a new version, the session at his home studio was caught on film by a ‘Blue Peter’ film crew and was aired on the show in early 1979. It offers a fascinating insight and is well worth picking over.

Mike Oldfield wasn’t short of a bob or two, revealing in a 2013 interview with The Telegraph’s finance pages that of the first million he made from 1973’s multi-squillion-selling ‘Tubular Bells’ album, he paid £860,000 in tax and with the change he bought a house, The Beacon in Hergest Ridge on the Herefordshire/Welsh border. The house cost £80,000 and built a studio there with the rest. In 1976 he moved to Througham Slad Manor, near Stroud. A modest 16th century pile set in 15 acres, it had a couple of cottages out the back, one of which became Oldfield’s studio, which is where ‘Blue Peter’ and presenter Simon Groom found themselves for the recording session.

The point of the film was to show how “modern pop music” was put together. I recall seeing it at the time and being open-mouthed as Oldfield built up the tune, playing everything himself. This was, after all, his stock-in-trade having played all 40-odd instruments on ‘Tubular Bells’ himself. After the first guitar part is complete, presenter Simon Groom isn’t shy of asking the stupid question.

“It didn’t sound much like the ‘Blue Peter’ signature tune,” he says after the first guitar part is recorded, “but this was just the first rhythm track”. Oldfield whistles back the tape to check the first take. Hang on, it that a Studer A800 24-track two-inch tape machine? Check the glowing orange VU meters’, all 24 of them, as Oldfield bangs up the volume.

“The quality through those speakers is amazing,” remarks Groom, almost laughing at how good it must sound. Your standard backroom home recording studio this is not. Next up it’s three tracks on a bodhrán, the Irish drum that is so Oldfield it hurts. Acoustic bass goes down next and then things get interesting.

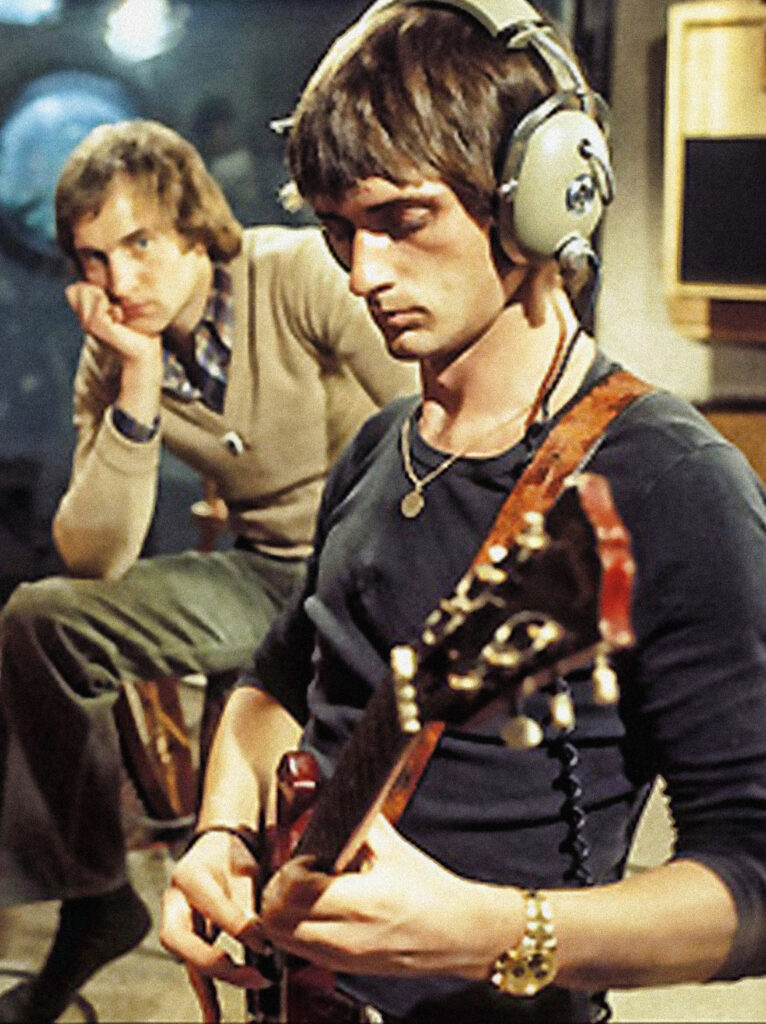

“As well as acoustic guitars and drums, Mike uses a lot of electronic gadgets called synthesisers,” says Groom. Sat crossed legged on the floor, you can see Oldfield with three synths, two stacked one on top of each other, one to his right. While the video is pretty fuzzy, a little detective work reveals that the synths on top of each other are a Roland SH-2000 and a string synth, the Solina String Ensemble, which was produced by a Dutch organ company called Eminent, and later rebadged by ARP. The machine to his right looks very much like an ARP 2600. We know he had one as you can see it in a shot, taken in 1976 at Througham Slad Manor, of Oldfield and his instrument haul neatly laid out on the floor like an OCD case study.

Back to the track and he heads straight for the Solina String Ensemble and puts down some big chorded string swells.

“It sounds great,” offers Groom, about to backhandedly beat up on Oldfield, “but when are you actually going to add the signature tune?”

Cheeky bugger. Oldfield used the SH-2000 a lot, in particular the clarinet preset, laying it down at half speed to create that distinctive recorder-like sound that is spread so liberally across his early albums. And sure as eggs is eggs it’s the SH-2000 he fires up next.

“What’s the difference between this synthesiser and the one you’ve just played?” asks Groom.

“Basically no difference except that this one has got all preset sounds, I’m using a clarinet sound, but speeded up it sounds like a recorder,” says Oldfield.

BOOM! So why does he have to slow it down?

“Because I can’t play it that fast,” he laughs. The new-fangled kit also causes him another problem it would seem.

“Mike’s fingers are those of a typical guitarist, he uses his long nails to pluck the stings, though it can’t be too easy playing the keyboard,” offers Groom.

While we don’t see anything beyond these three synths, a little more digging reveals that at the time he also owned a Sequential Circuits Prophet-5 and a Moog Polymoog, but clearly neither were pressing his buttons that day. Anyway, back to the session. Oldfield is now at the mixing desk playing back proceedings so far. Sounds like the theme tune to us… but he’s not happy. He scratches his head and announces he’ll use the film crew, who are “pretending not to be here”, for a bit more percussion.

Bells, tambourines, triangles and anything shakeable or hitable get two takes before he’s cheered up. He adds a bright lead electric guitar part and “a couple more synth tracks” before getting Simon Groom, who is apparently a drummer (who knew?) to add the opening drum roll. Next comes the mixing.

“Mike is a perfectionist,” explains Groom, “every track had to be played back at precisely the level he wanted. He kept playing the tape over and over again making minute adjustments, it took around an hour before he was happy.”

An hour? Bloody hell, someone tell Simon Groom that’s quick! The end result was imprinted on young ears for a generation. So did Mike Oldfield get a ‘Blue Peter’ badge for his trouble? “Yes,” he told The Guardian in 2014, “I’ve still got it, proudly, in a box somewhere. Forget ‘The Exorcist’, winning a Grammy or having a No 1, ‘Blue Peter’ came to see me!”