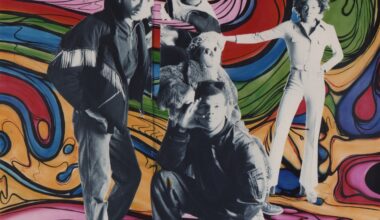

Looking back through the mists of time to 1980, Andy Mccluskey talks us through the making of OMD’s smash hit single. Synths out of a catalogue, a scandal with ‘Swap Shop’, Airfix models – it’s a tale that’s got it all

I had wanted to write a song about Enola Gay for some time. Both Paul Humphreys and I grew up being fascinated by Second World War airplanes and were complete Airfix anoraks. If you’re interested in Second World War aircraft, you eventually come to the Enola Gay B-29 Superfortress, which, despite being the most technologically-advanced pressurised aeroplane, was still somewhat primitive and Heath Robinson-esque in comparison to modern planes, and I think that was part of the fascination.

When you start to research the story, it has a very complicated human and moral – some would say immoral – dimension, the most bizarre thing about it being that Enola Gay was the name of the pilot’s mother. He believed he was doing something that was morally right. Things are done in warfare that are beyond the normal understanding of humanity, morals or ethics. The Enola Gay story was a very, very deep subject, and yet I was quite concerned not to deliver the lyrics in a purely didactic way. I did want to make them slightly more obscure. To this day I don’t know why I chose to wrap the lyrics in what could be conceived as careful metaphor, to the point where some people thought it was a love song.

The music was completely intuitive. I’m not a trained musician, I can’t read or write music, so it was all done by ear. I sat down at an organ in the back room of Paul’s mum’s house – he was on a YTS scheme and had to go and rebuild a swimming pool – and I just sat there and I played the four chords in my usual three-fingered crabbed way, and started writing the melody. To this day I still can’t play the melody at full speed. All of the harmonics were just the notes that sounded right to me.

One of the most iconic parts of the song – the drum machine pattern on the Roland CR-78 – was actually the very last thing that went on the track. I can’t even remember why we decided that we wanted a drum machine. We thought it was maybe a bit boring to have a straight drum kit. The CR-78 was the first programmable drum machine. Most drum machines in those days had Rock 1, Rock 2, Waltz and so on, and you just pressed buttons and it played the rhythm, but the ‘Enola Gay’ pattern was completely programmed by us on the CR-78, it wasn’t a preset.

There are acoustic drums on the song, but they were not played as a live kit. Our poor drummer Malcolm Holmes was driven to distraction by this because we didn’t want the drums playing in a rock ’n’ roll, clattered style. We insisted that he put down each drum separately, and no cymbals were allowed, and that took a long time. That actually created a problem, we had to add in the big fill that comes back out into the last melody, because he’d missed a beat. We refused to go back and fix it because it had taken so long to put the drums down.

Everything on ‘Enola Gay’ was played by hand. It was before computers and sequencers and before MIDI. Everything was following the CR-78 drum machine. The melody is triple-tracked which gives it its fat harmonic sound, but because it’s all played by hand, each note doesn’t land in exactly the same place. It means it’s got a slightly wandering, multi-timbral fuzziness to it.

We used a Korg Micro-Preset and a Roland SH-09 for the melodies. We also used an old 1960s Vox Jaguar organ banged through a load of reverb and harmonisers to make it sound less tinny. We bought the Korg from my mother’s catalogue. It was £7.36 for 36 weeks, which was all we could afford out of our dole money. It is one of the most primitive synthesisers you will ever come across. It’s got a series of buttons for different instrument sounds, but it doesn’t matter what button you press, the synth just goes ‘ennnnhhhhhhhh’. That’s one of the reasons our early synth parts are triple-tracked and swamped in reverb, to try and make the sound slightly less like an electronic kazoo!

We recorded the track with Mike Howlett. Mike was put in with us because we were a bit crash-bang-wallop in the early days. We didn’t really know what we were doing and so he was installed to slow us down. He did a good job, produced three of our biggest singles, but he also allowed us to do it our way. We did things in a way that no other band would do, partly because we refused to follow what we perceived to be rock ’n’ roll cliches and partly because we didn’t know any better! He didn’t come in and say, “That’s not the way you do it”. If a producer had come in and done that, first we’d have probably had an argument with them, and second it wouldn’t have sounded as distinctive.

[Saturday morning BBC TV children’s show] ‘Swap Shop’did ban the track. They were concerned about the use of the word “gay”, that the song was some sort of surreptitious way of trying to corrupt the youth because they couldn’t work out what the lyrics were about. They thought it was a homosexual anthem masquerading as a pop song, but yet apparently about an aeroplane to make it seem like a red herring. Another of the issues that we encountered at the time was people saying we had a song that was about something that was frankly appalling and yet it was in the charts, people were dancing around to it, it had a jolly, bright candy floss melody – how could I justify that? Frankly I couldn’t. My only defence of writing a cheerful pop song about such a dark period of human history was to say that it’s less strange and surreal than it is to drop an atom bomb from an aeroplane named after your mother.‘Enola Gay’ is absolutely a song I still enjoy. I don’t really understand the mentality of people who feel that their hits become some sort of albatross. It’s a blessing to you, you should celebrate it and when you have an opportunity to play it live you should treat it with the respect that it deserves, and which the audience are going to give it. Don’t go out there and make excuses and mess around with it by doing some acoustic version of it. Go out there and play it the way you wrote it and the way it’s supposed to be heard. I have no time at all for people who whinge that they’re bored of playing their hits. It’s like saying you’re bored of your eldest child. I don’t understand it at all.