Electroacoustic musician Beatriz Ferreyra, who has been composing since the 1960s and still works every day in her home studio in France, talks about walking out on Stockhausen, recording in stairwells, and her fascinating new album ‘Huellas Entreveradas’

Deep in the Normandy countryside, down a long, single-track lane, is a peaceful and isolated former farmhouse. Electroacoustic composer Beatriz Ferreyra, who is now in her 80s, manages the property herself with extraordinarily youthful energy and dedication – fixing the roof and cutting trees during the day, as well as working in her studio late into the early hours. This tranquil yet busy home life is combined with a rigorous worldwide touring schedule.

Born in Argentina in 1937, Ferreyra moved to Paris in her 20s and has been based in France ever since. In March 1963, she attended a concert in Paris by Pierre Schaeffer, after which she asked her friend Edgardo Cantón, an Argentinian composer who worked at Schaeffer’s Groupe de Recherches Musicales (GRM), to introduce her. She was subsequently hired to compose and edit for Schaeffer’s musique concrète experiments. Pre-dating synthesisers, these were based around the looping and manipulation of any recorded environmental sound to make music.

Ferreyra also attended workshops in the German city of Darmstadt with Karlheinz Stockhausen, György Ligeti and Earle Brown. I suggest that she had some pretty good teachers early in her composing career.

“I never had a teacher for the techniques of electroacoustic music,” she says. “The only teachers that I had were for the piano – Celia Bronstein in Argentina and Nadia Boulanger in Paris for eight months. I also did workshops with Earle Brown, who was very interesting for improvisation, and with Ligeti, for understanding tension. And Stockhausen? Well, I walked out after 10 minutes. He had too many rules. I think we must search for ourselves. We had no rules. We either liked it or we didn’t and nobody told anybody else what they were doing. We each developed our own way. Schaeffer taught us how to listen and hear. That’s all.”

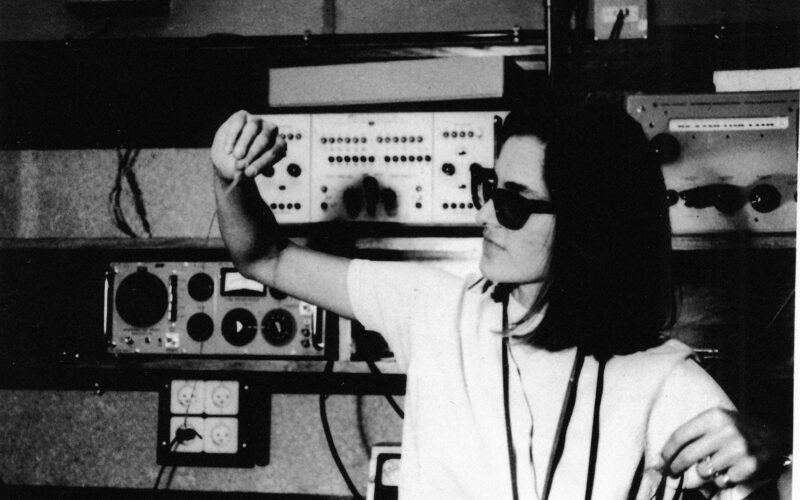

Beatriz Ferreyra currently uses Pro Tools with GRM plugins, but she began composing with mono tape recorders and a couple of filters. It’s been 60 years since her earliest pieces and 53 years since her first formal commission from Schaeffer’s GRM studios. So how have things changed during that time?

“When you begin to compose, you are one person,” she says. “When you are 83 years old, you are another person. You’ve had a life. I’ve forgotten lots, but I’ve learned an enormous amount, little by little. Now I make things technically different to when I was young. In 1963, I had one filter and I could have two or three different tape speeds for the same sound, to give high or low pitch, and then it was mixing and cutting. Everyone tried different ways with it, because you didn’t have anything else. If you want to do that with the Revox, you need patience, but back then that was the technology you had available. With the computer, you have a lot of plugins like that now. We didn’t have all this.”

Ferreyra left the GRM and began working independently in 1970. She received commissions from many of the leading centres of electroacoustic music, including the IMEB (Institut International de Musique Électroacoustique de Bourges), where she had several composer residencies in the early 1970s, and also undertook some film and television projects that enabled her to gradually build up her studio. At this point, it comprised two Dynacord filters, three Revox and two Uher recording machines, and a specially designed synchronisation unit for remote start and stop, an innovative piece of equipment for its time built by engineer Jorge Agrest. A Synthi AKS was added in 1972, although used only occasionally.

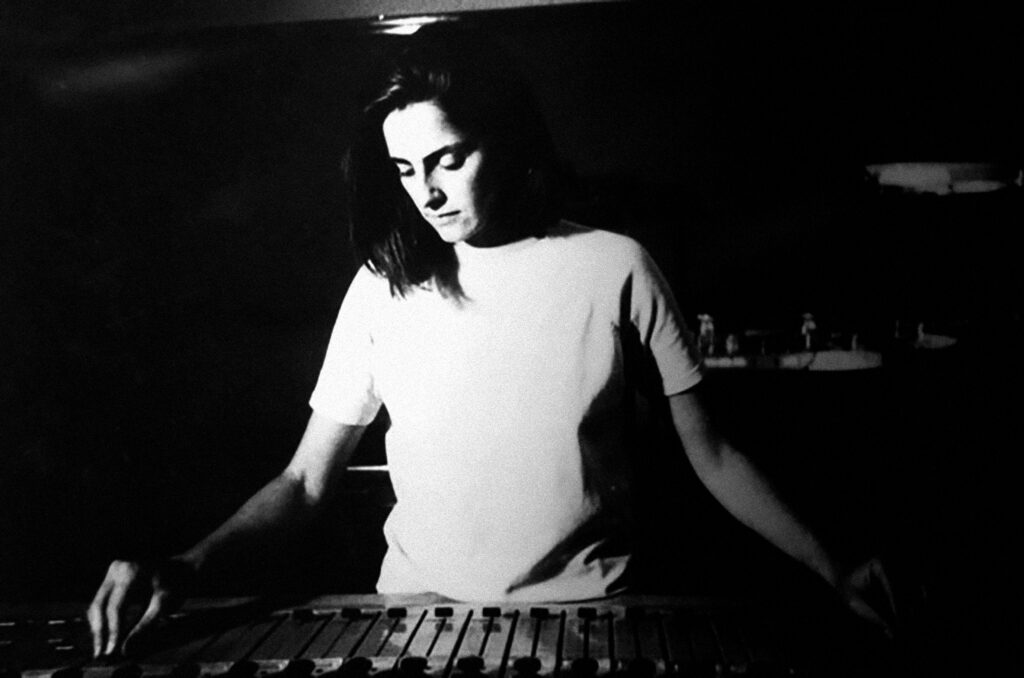

Even now, working digitally on a computer, Ferreyra’s practice is always informed by her experiences with analogue tape – slowing down and speeding up, reversing and looping, delay and feedback. Other techniques she used included rhythmically tapping the tape as it passed across the heads to create vibrato, nudging it very slightly away from the record head for a muffled sound with a loss of high frequency, and holding it in both hands and sliding it backwards and forwards across the record and playback heads to create varying rhythms in different tempos, similar to a DJ scratching. Another effect she achieved by the sudden starting and stopping of a machine while in record, then slowing this sound down.

In essence, Ferreyra played the tape machine like a musical instrument. In hindsight, working with this medium was slow and laborious. But in the 1960s, it was the new music technology.

“Technically, I prefer composing in the computer because I don’t need 20 tapes, I don’t need to put the sounds in another tape and another tape,” she says. “Synchronising tape machines was the work of dogs to get it right for the mixing. You had to always use exactly the same machine, because none of them were precisely the same speed. So on another machine it would be too late or too early and I found myself with a complete mess! With the computer, it’s marvellous. You can have 20 or 40 sounds at the same time. I don’t know how many tracks I have on my Pro Tools. But I do still use my tape machines for certain sounds that you can only make that way. You can’t make comparisons with technology. You manage with what you have at the time. It’s easier now, but in another way it’s more standard.”

“Standard” is anathema to Ferreyra. She always records her own natural environmental or vocal sound sources, which she perceives to be more “alive” than using pure electronics.

“I prefer natural and vocal sounds. Sounds that are very electronic don’t interest me so much. I just listen and I mix. My manipulations are simple, from the time of the tape machines – fast, slow, low, high, some filtering. It has nothing to do with the latest machine that everyone uses. I combine elements together in a certain way and that’s how I make the Ferreyra sounds. It’s much more personal, you see.”

In March of this year, the Australian label Room40 released ‘Echos +’, a collection of three of Ferreyra’s most engaging compositions – ‘Echos’ (1978), ‘L’Autre… Ou Le Chant Des Marecages’ (1987) and ‘L’Autre Rive’ (2007). A brand new Ferreyra album, ‘Huellas Entreveradas’, followed in April on Persistence Of Sound.

“Beatriz’s music is clearly from the classic musique concrète school,” says Iain Chambers from Persistence Of Sound. “Her aesthetic comes from composing with tape. There’s this amazing sense of movement and transformation and great humour too.”

The concept of motion is significant in all of Ferreyra’s works, right from her first commissions, ‘Demeures Aquatiques’ (1967), the meeting point of the ebb and flow of the tide, where abstract watery resonances approach, recede and swirl around the listener, and ‘Médisances’ (1968), in which whispering vocals travel around in varying rhythmic trajectories. A feeling of rhythmic movement also persists in the title track of ‘Huellas Entreveradas’, which takes up the whole of the first side of the album.

“‘Huellas’ is the footprint of everything, such as living things and things that you remember,” explains Ferreyra. “‘Entreveradas’ is when you have more than one set of footprints going up, going down, crossing over, people or animals, and it makes a little bit of a mess.”

Ferreyra’s mischievous streak is highlighted in the two other tracks on the album. ‘Deux Dents Dehors’ (‘Two Teeth Sticking Out’) is a pun on composer Bernard Parmegiani’s ‘Dedans Dehors’ (‘Inside Outside’), while ‘La Baballe Du Chien Chien À La Mé-Mère’ (‘The Ball Of The Old Lady’s Dog’) mocks the childish speech used by pet owners. All three pieces on ‘Huellas Entreveradas’ suggest a fantastical journey, as sounds move through close and intimate to vast and cavernous spaces. High-pitched percussive whisperings zip around the stereo image, punctuating a continuous layering and interweaving of rich drone-like textures.

Many of Ferreyra’s titles also give a sense of the space expressed in her music – ‘Echos’, ‘The UFO Forest’, ‘Dans Un Point Infini’ and ‘L’Autre Rive’ – some of which hint at her life-long passion for astrophysics. I ask her about her use of space and the idea of an abstract narrative or journey between different acoustics.

“Ah, a journey? Well, everyone feels the music in different ways. Space is something simple. At first, I did the music in mono with tape. I wanted to have the sound like in life. You have a car coming from right to left, you have a plane up there, you have birds all around, you have something far away and something very near. The only movement I could have, though, was from very far to very near. I couldn’t have left and right, because I had only mono. You cannot imagine this kind of thing now. I couldn’t have up and down, only high or low pitch. So all these differences had to be within the sound itself. Now stereo gives this, you have infinite points to move your sound between left and right, very far and very near. But the music has been composed with movement already in it. The space is in the music.”

Working with reverb for different acoustics has always been a key part of her practice, even before reverb units existed.

“When I was living in a building in Paris, I went with my microphone into the stairwell of 12 floors to do the reverberation. That’s where I recorded the resonance, from the cage underneath the lift. At that time, the echo rooms were enormous and cost a fortune. Even later, when I had the AKS synthesiser, it had reverb on it, but it was electronic and that didn’t interest me so much. When I was invited to Bourges every two years, I did all my reverberation in the big studios. When I came to my studio here, I had tape delay. But whenever I was in Paris, I always went back to that place on the stairwell. That’s why I had a reverberation that sounds as if I was in a cathedral.”

In Beatriz Ferreyra’s studio these days, the computer sits in the middle of the room with a mixer to one side and her three Revox tape machines still very present on a shelf to the other side. A set of eight monitor speakers surround her, suspended from the ceiling. All her concert work is delivered through multi-loudspeaker configurations, needing at least eight speakers around the audience, and this is how she listens while composing. She still travels to perform her work in person, however she is clear that the most important thing about the presentation is that everybody listening has the right balance of sounds, not that the attention is on her.

“I’m not a performer,” she says. “I don’t interpret or spatialise. I do this only for that reason. I’m just thinking about the audience.”

We end the interview so that Ferreyra can finish mixing cement for the floor to a new woodshed she is building. Her routine of working all day outside to maintain her farmhouse and making music in her studio in the evening continues. Before we say goodbye, I ask her what advice she would give to new electroacoustic composers of today.

“Don’t copy. Be yourself. Continue to try to do whatever you feel.”

‘Huellas Entreveradas’ is out now on Persistence Of Sound