Roland’s TB-303 bass synthesiser was not a commercial success and was only on the market for a couple of years. But in the hands of a small group of Chicago musicians and producers the little silver box created the squelch for Acid House and sparked the revolutionary illegal rave scene that followed soon after

The Birth of Incantation

It’s a pleasant summer’s day in July 1988 and I’m sitting outside a cafe in north London, a couple streets from Camden Town tube station. Across the table from me is a charismatic and very dapper young guy. He’s wearing a shiny gold jacket with tassels across the shoulders and down the sleeves. He’s smiling broadly and speaking slowly, his eyes blazing bright as he tells me how much he loves Led Zeppelin and Pink Floyd and Cream. Which is really not what I’d expected from Marshall Jefferson, one of the key figures of the early Chicago house music scene.

Marshall Jefferson’s ‘Move Your Body’, released on Trax Records in 1986, remains one of the greatest club records of all time. In some ways, it was a legend of its own making. Subtitling the track ‘The House Music Anthem’ wasn’t subtle, but it was certainly accurate. The opening refrain – “Gotta have house music all night long” – continues to set the agenda for countless clubbers to this day.

Jefferson was a writer and a producer as well as a recording artist in his own right. He’s often cited as one of the pioneers of the soulful deep house sound, but his work on Sleezy D’s ‘I’ve Lost Control’, which he produced under the alias Virgo, was at the opposite end of the sonic spectrum. ‘I’ve Lost Control’, recorded in 1984 although it didn’t make it onto vinyl until two years later, is a 10-minute onslaught of pained shouting, manic laughter, weird squelchy noises and clattering beats. It was raw and harsh and every bit as unsettling as Suicide’s ‘Frankie Teardrop’ had been almost a decade earlier. The big difference was you could dance to it.

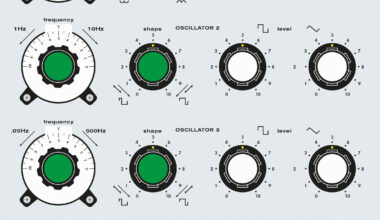

The music on ‘I’ve Lost Control’ was made on two Roland machines – a TB-303 Bass Line and a TR-808 Rhythm Composer, better known as simply a 303 and an 808. The squelches, which is was what set the track apart, was the result of some serious tweaking of the 303 bass synthesiser, a technique Jefferson had reportedly been shown by fellow Chicago house pioneer Adonis. Until that point, the 303 was probably best known for Heaven 17’s ‘Let Me Go’, Orange Juice’s ‘Rip It Up’ and Newcleus’ electro classic ‘Jam On It’, but the little silver box was not a commercial success and had been discontinued by Roland after only a couple of years on the market.

Sleezy D’s ‘I’ve Lost Control’ oiled the first cogs, but it was another Marshall Jefferson production that started the engine of what became known as acid house. Phuture’s ‘Acid Tracks’, released on Trax in 1987, was fabulously trippy and utterly irresistible. The three guys in Phuture – DJ Pierre, Spanky and Herb J – had a 303 of their own and they used it to create even wilder sounds than Jefferson. Whenever legendary Chicago DJ Ron Hardy played ‘Acid Tracks’ at The Music Box, the crowd went ballistic. They just couldn’t get enough of it. Despite the record being 12 minutes long, it wasn’t unusual for Hardy to play it three or four times a night. By the time it was having the same effect on UK club crowds in 1988, the distinctive acid noise was the central feature of dozens of records coming out of Chicago every week.

“I started out wanting to do something different and now look what’s happening,” Jefferson told me as we sat in the Camden sunshine, noting that he blamed DJ Pierre for revealing to everybody that the 303 was the source of the squelch. “I thought the pattern would be too complicated to duplicate, but once they found out the formula, they’d all gotta have one of them acid machines. Now everybody’s on it, everywhere you go the acid is pumping, and you can’t match the energy level. How you gonna get ridda the acid, man?”

The Road To Utopia

The UK club scene of the mid-1980s was seemingly irrevocably split between the north and the south. Electro was still a huge draw in Manchester, for example, and the first house records that came into the UK from America were viewed as having similar rhythmic properties and warmly welcomed as a result. Mike Pickering, who began his Nude nights at The Haçienda in 1986, was one of the first British DJs to play house music. Other eager early supporters of the genre were Graeme Park, who had a residency at The Garage in Nottingham and later co-hosted Nude with Pickering, and Winston Hazel and Richard “Parrot” Barratt at Jive Turkey in Sheffield.

In London, meanwhile, the nightlife soundtrack was largely hip hop and rare groove. Apart from at a few isolated clubs, most notably Pyramid at Heaven in Charing Cross, where Colin Faver and Mark Moore were the DJs, house music was not on the menu. And while Jazzy M’s ‘Jackin’ Zone’ pirate radio show was an important outlet for house, the show had a limited impact on London clubland. When the ‘Jackmaster House Tour’ brought Joe Smooth, Darryl Pandy and other Chicago luminaries to the Town & Country Club in November 1987, the place was two-thirds empty.

At almost exactly the same time, however, something was stirring on the other side of the town. Paul Oakenfold, part-time DJ and part-time agent for Def Jam in the UK, had journeyed to Ibiza to celebrate his birthday at the end of August, taking several of his music biz mates with him. The group had especially enjoyed their visits to Amnesia, where DJ Alfredo played a mixture of house, euro disco and pop to the holiday crowds. When he returned home, Oakenfold began holding “Ibiza Reunion” parties at The Project in Streatham, with his focus increasingly on the latest tracks coming out of Chicago, including some of those oddball acid records.

Danny Rampling, who had been with Paul Oakenfold in Ibiza, was similarly inspired, starting his own night in the basement of the Fitness Centre in Southwark in December 1987. He called it Shoom. The place was small and was an actual gym by day, so the decor was very DIY and mainly consisted of sheets painted with yellow smiley faces hung from the walls. The crowd included lots of music celebrities – Boy George, Martin Fry and Paul Rutherford were all regulars – with Rampling’s wife Jenni deciding who came in and who didn’t.

With 1988 underway, Oakenfold moved his club night to the West End, first launching Future at The Soundshaft and then Spectrum at Heaven soon after. While Shoom was intimate and selective, Spectrum was a grand affair, both in size and ambition. The flyers proclaimed Spectrum to be “The Theatre Of Madness” and it wasn’t wrong. With its flamenco dancers and its strawberry scented smoke and the huge eyeball dangling from the ceiling, Spectrum was acid house at its most decadent, its most daring. So daring that Oakenfold would occasionally plunge the whole club into darkness and chuck on the bells and cannons finale of Tchaikovsky’s ‘1812 Overture’.

“I was scared at the start,” admitted Oakenfold. “I thought I was going to fuck up and lose a club full of people. The odd acid track would clear the floor. The more I played, the more people complained. But I told them that if they wanted rap, they should go someplace else, I wasn’t interested anymore. Sometimes you’ve got to say, ‘I’m really into this, I believe in it, and I’ve got the bottle to go through with it’.”

Shoom and Spectrum were the catalysts for scores of other clubs springing up in London’s West End in the summer of 1988. Nicky Holloway, who’d been taking party groups to Ibiza since 1985, ran Trip at The Astoria. M/A/R/R/S man Dave Dorrell hosted Love at The Wag Club. Steve Proctor, who began his DJ career playing Bowie and Roxy at futurist nights in Liverpool, had Elysium at The Limelight. There were dozens more and every place, every night, was packed out with people dancing non-stop for hours on end. As the year progressed, the smiley faces spread across many other UK cities too, with acid tunes becoming increasingly popular in the house music citadels of the north and new scenes developing in places like Liverpool and Glasgow too.

As for the music, acid house was a broad umbrella. The clubs played lots of 303 tracks, of course, but there was plenty of variety to them. The chilling vibe of Bam Bam’s ‘Where’s Your Child?’ couldn’t be more different to the gently hypnotic ‘Dream Girl’ by Pierre’s Fantasy Club, the Pierre in question being Marshall Jefferson’s old pal from Phuture, and there was no confusing Fast Eddie’s ‘Acid Thunder’ with Tyree Cooper’s ‘Acid Over’. In stark contrast to the commercial house that became the staple fare of the 1990s superclubs, these records were experimental, challenging, often dark and sometimes dangerous. Master C & J’s sinuous and sinister ‘Dub Love’ is a case in point.

Alongside the American releases, there was a scattering of UK acid tracks too – A Guy Called Gerald’s ‘Voodoo Ray’, Bang The Party’s ‘Release Your Body’, Ecstasy Club’s ‘Jesus Loves The Acid’, Humanoid’s ‘Stakker Humanoid’ – while 808 State delivered ‘Newbuild’, the first British acid album. But before any of these, came Baby Ford’s head-spinning ‘Oochy Koochy (FU Baby, Yeah Yeah)’, which was released on Rhythm King in June 1988 after someone from the label had heard a tape of it at Shoom. “It’s the sort of record that shits on your turntable” was how one journalist described it. OK, I’m going to own up to that line. I’m still quite proud of it.

“I love the idea of dodgy samples and a voice going ‘Bleurgh!’ in your face,” explained Peter Ford at the time. “The chorus doesn’t come in until half way through and people will think, ‘Why the hell’s it called “Oochy Koochy”, all I’ve heard so far is “F-f-f-f-f-f-you, yeah yeah”.’ At the end, most tracks build up, but that seemed too obvious, so we took the bass out. But the whole thing works. I’d say it’s 75 per cent right with 25 per cent human error. That’s fine. Bring back human error.”

For most DJs, it wasn’t only about the squelch, though. There were straighter house tracks such as Adonis’ ‘We’re Rocking Down The House’, Raze’s ‘Break 4 Love’ and Frankie Knuckles’ ‘Baby Wants To Ride’. There were deep house cuts like Fingers Inc’s ‘Can You Feel It’ and breakbeat workouts like ‘Can You Party’ and ‘A Day In The Life’, credited to Royal House and Black Riot respectively, but both the work of New York producer Todd Terry. There was Detroit techno in the form of Derrick May’s ‘Strings Of Life’, issued under the name Rhythim Is Rhythim, and Inner City’s ‘Big Fun’. There was Belgian new beat, most notably Miss Nicky Trax’s ‘There’s Acid In The House’. There were EBM frugs like Nitzer Ebb’s ‘Join In The Chant’ and industrial monsters like Finitribe’s ‘De Testimony’.

The last couple of these fell under the catch-all description of “balearic beat”, although I must admit I was never quite sure what this was meant to be. Whatever it was, I loved the eclectic playlists of so many of the acid house DJs. Yello, The Gypsy Kings, The Woodentops, It’s Immaterial, Front 242, The Residents, The Thrashing Doves and even Natalie Cole’s ‘Pink Cadillac’ were part of the mix. I seem to remember Steve Proctor playing The Rolling Stones’ ‘(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction’ one night, slightly slowing it down from its 136 beats per minute, and it worked a treat.

North of Watford, meanwhile, the likes of Mike Pickering and Graeme Park were a little frustrated at how cool and hip everybody suddenly thought the London club scene was. They were keen to point out that they were on the acid trip too and they’d started their journey long before Paul Oakenfold had blown out the candles on his birthday cake in Ibiza.

“Why weren’t they into it a year or 18 months ago?” pondered Park. “Up here, it’s true to say that people are, on the whole, less dictated to by fashion and that’s probably the main reason why it took off here long before it did in the south. I’ve had packed dancefloors with electric atmospheres for ages and I’ve been playing very similar material. As for balearic beat, that’s just an excuse for trendy DJs to play what are quite often crap records.”

While we have you, why not take a minute to browse our online shop?

We’ve got print magazines, limited edition vinyl, must-have books, CD boxsets, and we ship worldwide. Click below to open a new tab and keep your current reading place.

Fairground Rides And Heavy Bastards

We need to talk about drugs. We need to talk specifically about ecstasy, of course. Known to the chemists as 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine. Known to the clubbers as E or MDMA. First synthesised by the German pharmaceutical company Merck in 1912. Patented in 1914 and again in 1921. Found in the files at Merck’s Darmstadt factory by American military intelligence officers in the aftermath of World War II. Tested by the CIA as a potential “truth drug” in the 1950s. Used in psychotherapy in the 1970s and early 1980s across the US, where it remained a totally legal substance until 1984.

The legal status of ecstasy was very different in the UK. As part of the amphetamine family, MDMA fell under the 1971 Misuse of Drugs Act, so it was already outlawed as a Class A substance when small quantities started arriving in the UK from the US in the early 1980s. By the time the country was in the grip of acid house, it was coming in from Europe and on a much bigger scale. It was also being manufactured here.

It’s not true to say that everybody going to acid clubs took ecstasy. But a lot did. And there were casualties. The first ecstasy-related death in the UK was that of 21-year-old Ian Larcombe, who suffered a fatal heart attack as a result of popping 18 MDMA pills in June 1988. Four months later, at the end of October, Janet Mayes collapsed and died after taking just two pills at an acid party at The Jolly Boatman pub in semi-rural Hampton Court. She was also 21 years old. The newspapers had barely mentioned Ian Larcombe’s death, but they took the opposite approach to the Janet Mayes story. The Sun put it on the front page under the headline “Shoot These Evil Acid Barons”.

Galvanised into tougher action by the media reaction, the police swooped on a number of acid nights the following weekend, with raids all over the UK, from London and the Home Counties to Manchester, Sheffield and the West Country. Most of the targets weren’t clubs, they were unlicensed raves in disused warehouses and factory units. At Sevenoaks in Kent, they busted a party in a large derelict house, the walls of which were daubed with smileys. It took 60 officers two hours to bring the 250-strong crowd under control. They even raided an event on a Thames pleasure cruiser moored at Greenwich Pier, with the river police swarming on board from launches and frogmen circling in the water, ready to act if anybody jumped or fell in.

The number of illegal raves spiralled during the first half of 1989. Every empty space was fair game for the promoters. Most of the events were in the bigger cities, but one of the earliest and strongest scenes was based around the town of Blackburn in Lancashire, initially with a hardcore local audience of around 300 but soon drawing in people from Manchester, Liverpool and Leeds as word spread. An all-nighter called Live The Dream that took place in September at Tockholes, a village to the south of Blackburn, attracted an estimated crowd of 10,000. Paul Oakenfold and Nicky Holloway were among the DJs.

With the onset of the warmer weather, rave promoters switched their attention from urban centres to the countryside, organising large-scale outdoor parties in fields, chalk pits and forest clearings. The biggest promoters, the likes of Sunrise, Biology and Energy, operated around the newly opened M25. The raves were advertised on flyers in record shops and on pirate radio stations, most notably Centreforce, with people calling automated phone lines on the night to be directed to the location. Some of these were massive events, attracting many thousands of ravers. There were euphoric sounds – Lil Louis’ ‘French Kiss’, Model 500’s ‘The Chase’ and 808 State’s ‘Pacific State’ were among the big tunes of 1989 – and eurhythmic lightshows. There were thick gushes of dry ice and incredible firework displays. There were fairground rides and bouncy castles.

For the police, the rash of orbital raves meant one giant-sized headache after another. Especially for Chief Superintendent Ken Tappenden, divisional commander of north-west Kent, an area split in two by the M25. The southern side of the Dartford Crossing, the only way to get over the Thames east of London, fell within his jurisdiction. Following the bust at Sevenoaks, which was also on his patch, Ken Tappenden had set up an incident room at Dartford police station to investigate the acid party phenomenon. And it wasn’t long before he was getting calls from countless other police stations all over the UK.

By the summer of 1989, Tappenden’s team transferred to Gravesend, acquiring the name the Pay Party Unit along the way. The ravers called it “the Acid House Squad”. From his original group of six officers, the Pay Party Unit became a national force, boasting a staff of around 250 and incorporating satellite detachments in 12 police forces. Tappenden adopted all kinds of tactics to disrupt the parties. Officers were sent into clubs and record shops to confiscate flyers. Landowners and trucking companies were served with injunctions. From Wednesdays onwards, police helicopters would be looking out for steamrollers on the move, the rollers often being used to flatten sites. They even set up their own pirate radio broadcasts from the Gravesend office, with younger officers giving out false information on the airwaves.

The Acid House Squad’s biggest single success came in October, when it stopped a Biology rave near Guildford in Surrey, at which a crowd of 40,000 had been anticipated. I was one of the countless people stuck in a car on a country lane for hours that night because of the police roadblocks. For the ravers, the police were killjoys, of course, determined to stop their fun just because they were playing loud music and popping a few pills. Most of them had no idea about the very ugly activities going on beyond the peace and love vibe of the rave scene. Promoters faced extreme violence from all manner of criminal gangs. One of them found himself bound, gagged, and with a gun stuck to his head. DJs and artists were forced to bring drugs into events. Record shops were repeatedly smashed up as a warning not to run parties without the gangs. The latter was a favourite tactic of the Inter-City Firm, the ICF, the notorious football hooligan outfit linked to West Ham United.

“The criminal element infiltrating the raves was more sinister than anyone at government level ever wanted to know and more sinister than the public ever perceived,” Ken Tappenden told me when I interviewed him after he’d retired from the police force in 1993. “Lots of the names that kept coming up were people we knew. They were gangsters. They were thugs. They were heavy bastards. Across-the-pavement robberies were going down and drug-related crime was going up. Yes, we had kidnappings. Yes, we had beatings. Yes, the ICF got involved. Some people got seriously hurt, seriously maimed. The message was, ‘You don’t want to look like him next month’.

“We also saw it in the fields. We recovered four sawn-off shotguns in one night at a rave at Ockenden in Essex. We filmed security men making Rotweiller dogs attack people at Reigate in Surrey, putting 16 in hospital. And it was never-ending. The moment we took one team of five villains off, another five would come in. I thought we would have mass slaughter with the gangs. I talked about the danger of a Hillsborough-type disaster if it suddenly went off at a crowded party. It didn’t ever happen, but it’s no exaggeration to say we were often on the brink of it.”

By December 1989, Tappenden was exhausted. He hadn’t had a Saturday night off for 15 months. He remembers how much he was looking forward to Christmas, how he believed the holiday period would give him and his team a much-needed break. The promoters had been running raves non-stop through the winter months so far and they needed a break too, didn’t they? As if. New Year’s Eve fell on a Saturday. The number of illegal events logged by the Pay Party Unit in that one single night was 126.

Breakin’ Rocks In The Hot Sun

Against pretty much everybody’s expectations, the first couple of months of 1990 saw a sharp decline in the number of illegal raves monitored by the Pay Party Unit in London and the Home Counties, down from an average of 30 every week in November 1989 to under 10 by February. At the same time, more and more calls were coming into the Gravesend office from the Midlands and the north of the country. This geographical shift became clearer as the year went on and the Kent-based office was closed in June, the Acid House Squad moving first to Warwickshire and then later to Liverpool.

What caused the sudden drop in rave activity in the south? The constant pressure from the police undoubtedly had something to do with it. At the end of 1989, the Pay Party Unit had won a significant victory when they persuaded the controlling body of the Telephone Information Services to stop British Telecom hiring voice banks to known rave organisers, pulling the plug on the automated phone lines that were crucial to the smooth running of every party. Ken Tappenden, however, has always believed that the continuous threats of violence against the promoters had far more impact than anything his squad ever did.

The changes in the rave scene may also have been partly due to the progress through parliament of the Entertainments (Increased Penalties) Bill, giving courts the power to levy fines of up to £20,000 and jail anyone organising an unlicensed party for six months. To further bolster this legislation, which was sponsored by Graham Bright, Conservative MP for Luton South and later Parliamentary Private Secretary to Prime Minister John Major, the police were granted additional powers to confiscate equipment found at illegal events.

The Entertainments (Increased Penalties) Act was passed into law in July 1990 and it wasn’t long before the authorities flexed the extra muscle it gave them. Just one week later, a party at a warehouse near the village of Gildersome on the outskirts of Leeds ended with a massive police bust. Many of the officers taking part in the raid wore riot gear and some were on horseback. A staggering 836 people were taken into custody, the detainees held overnight in 26 different police stations across West Yorkshire. It was the biggest mass arrest in Britain since the Peterloo Massacre in 1819.