AR Kane came up with the term “dreampop” to describe the mind-blowing fusion of musical styles on their late 1980s albums. And as the new ‘AR Kive’ boxset confirms, their records remain every bit as strange, beautiful and irresistible as they were 35 years ago

‘We didn’t take any shit from anybody. As soon as we got a red flag, we walked. Looking back on it now, I think it was because we didn’t know what the rules were. We weren’t middle-class white kids and we found it difficult to read a lot of the people we met in the music industry. So every time we were told, ‘You’re going to do this in this way, you’re going to do that in that way’, we’d be saying to ourselves, ‘Yeah? Really? I don’t think we fucking are’.”

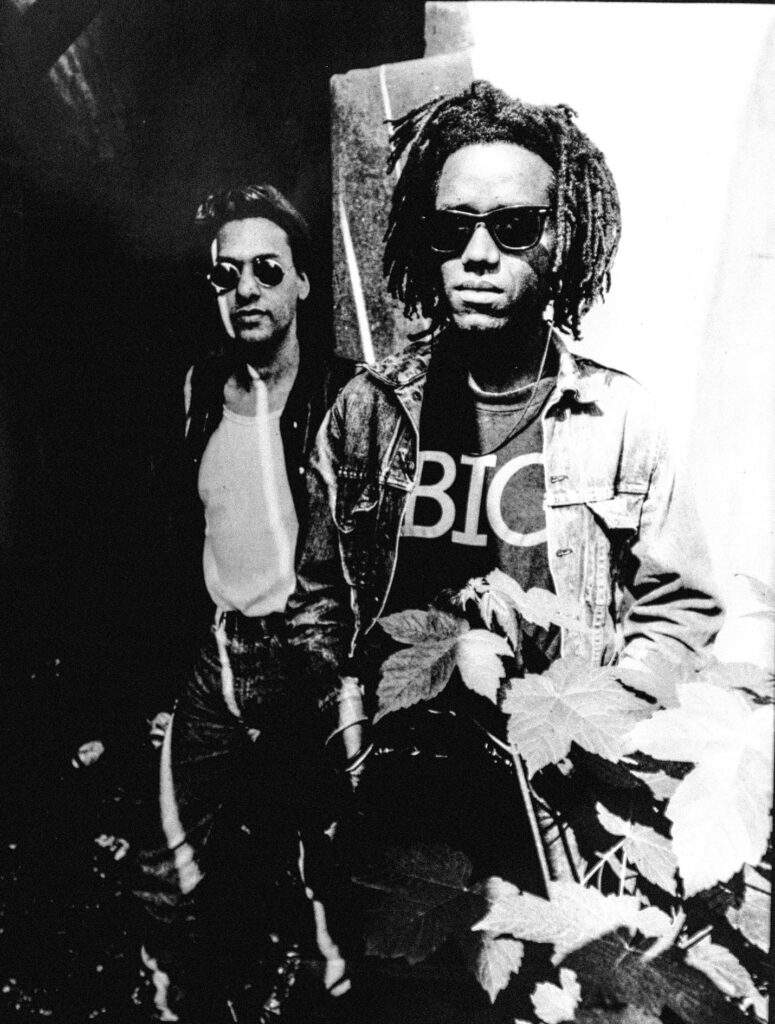

Rudy Tambala is talking about AR Kane, the group that he formed with his boyhood best friend Alex Ayuli in Stratford, east London, in early 1986. Over the next four years, powered by a relentlessly maverick streak and a confidence bordering on arrogance, AR Kane carved out a unique musical path, welding elements of pop, psych, dub, electronica, funk, noise, jazz, ambient and more in a way that had never been done before. Or since.

Even the most cursory listen to ‘AR Kive’, a reissue boxset on the Rocket Girl label which brings together the band’s first two albums, ‘69’ and ‘i’, proves the point. The ‘AR Kive’ collection is completed by their ‘Up Home!’ 12-inch EP, with the three records meticulously remastered by Rudy and sounding as extraordinary as they did when they were originally released on Rough Trade in 1988 and 1989. Their debut album in particular is a work of unbridled brilliance, extolled by the weekly music papers of the day and topping the UK independent charts with sales totalling 60,000 copies.

Alex and Rudy coined the term “dreampop” to describe themselves, but it didn’t really do the job. And it wasn’t enough that AR Kane didn’t sound like anyone else. Half the time, they didn’t even sound like AR Kane.

Alex Ayuli and Rudy Tambala met at Park Primary School, an austere Victorian structure overlooking West Ham Park, when they were eight years old. They were both of African descent – Alex’s parents were Nigerian, Rudy’s father came from Malawi – and they were immediately inseparable, remaining so for the next two decades. The pair have had very limited contact since AR Kane fizzled out in the mid-1990s, though. Rudy says Alex has not been involved in ‘AR Kive’, for example, but he has given the project his blessing.

An early shared interest for the two young friends was books, especially science fiction, which Rudy first got hooked on after borrowing Robert A Heinlein’s ‘Citizen Of The Galaxy’ and John Wyndham’s ‘The Chrysalids’ from his elder brother. As they edged towards their teens, the boys bonded over music as well, swapping records, compiling tapes for each other, and messing around on a mate’s guitar. It was only many years later, after they had seen the Cocteau Twins on ‘The Tube’, that they decided to have a go at making music themselves.

The first thing they did was choose a name. Dead Can Dance’s ‘Garden Of The Arcane Delights’ EP and Orson Welles’ ‘Citizen Kane’ movie were two inspirations, with the “A” and “R” of “Arkane” split out and representing the initials of their first names. They liked the idea of everybody thinking AR Kane was a person rather than a band.

The same night they settled on a name, they went to a party, where Rudy got chatting to a guy over a spliff and told him he was in a band. He said they were “a bit Velvet Underground, a bit Miles Davies, a bit Joni Mitchell and a bit Cocteau Twins”, four artists he had been listening to that day. Rudy’s weed buddy turned out to be Ray Shulman, a member of prog rockers Gentle Giant in the 1970s and by then a burgeoning record producer, who asked if he could hear a demo. Not that AR Kane had a demo. They didn’t have any songs. They didn’t even have any instruments.

“So we went out and bought two guitars and some effects and a little drum machine… and started making a demo,” says Rudy. “We had no idea what we were doing. We did everything on two cassette recorders. We would tape a guitar and some beats on one machine, then put that through a speaker while playing the other guitar and doing some vocals, and record everything onto the other machine. We did seven songs like that.”

However primitive AR Kane’s earliest recordings might have been, Ray Shulman was impressed. He took their demo to Derek Birkett, bassist with anarcho-punk outfit Flux Of Pink Indians, who had recently set up his One Little Indian imprint.

“Derek wanted to see us play live, so we booked this rehearsal room and put together a band,” says Rudy. “They were just people we knew, like an old school friend who had a bass guitar he couldn’t really play and my sister Maggie helping out on vocals. We were all black apart from Dan Goodwin, the drummer, who was later in Kitchens Of Distinction. Derek turned up with all these punk types and it was obvious they weren’t expecting us to look like we did. We weren’t good enough to do any of our songs live, so we basically did a set of noise.”

The story goes that Derek Birkett said, “You sound shit, let’s do a single”, and the result was ‘When You’re Sad’, a 12-inch produced by Ray and issued in the summer of 1986. Piled high with fuzz and feedback, the record prompted comparisons with The Jesus And Mary Chain and sold pretty well, but Derek dragged his heels about putting the band back into the studio. And while he dithered, Ivo Watts-Russell swooped in and grabbed AR Kane for 4AD.

“Derek really wasn’t happy about that, so he took his crew down to 4AD and started hassling them,” remembers Rudy. “It was just so bizarre, you know, Derek’s anarcho-punks offering out Ivo’s pale and skinny 4AD guys. We thought it was hilarious.”

AR Kane’s first 4AD release was another 12-inch, ‘Lollita’, this time with Cocteau Twin Robin Guthrie at the controls. Their second saw them teaming up with Colourbox under the name M/A/R/R/S – Alex and Rudy were the “A” and the first “R” – for the sampling masterpiece ‘Pump Up The Volume’ and its equally magnificent flip, the distorted epic ‘Anitina’. But the phenomenal success of the M/A/R/R/S record, a Number One in the UK and a Top 10 in 17 other countries, altered the relationship AR Kane had with their new label. But not in a good way.

“We loved being on 4AD, we loved having Robin Guthrie produce us, but the contract that they offered us was a really bad story,” says Rudy. “They thought we’d roll over just because of who they were, but we weren’t having it. I rang Ivo up from a telephone box at Maryland Point in Stratford and he said, ‘Rudy, either you sign this deal or you’re off the label’. The last thing I said to him was ‘Fuck off’ as I put the phone down.”

He pauses and chuckles.

“God, I’m coming across as a right narky git, aren’t I?”

In June 1988, a few months after the ‘Up Home’ EP had picked up where M/A/R/R/S’ ‘Anitina’ left off, AR Kane delivered the hazy, trippy, exquisitely otherworldly ’69’. They’d signed to Rough Trade soon after leaving 4AD, using the advance Geoff Travis had given them to build a small studio in the basement of Alex’s mum’s house.

With Alex determined to keep his full-time job as an advertising copywriter, they recorded the album in the evenings and at weekends. Ray Shulman, who was by now also working with The Sugarcubes, was a frequent visitor, playing bass on several tracks as well as helping out on the production.

From the colossal dub of ‘Baby Milk Snatcher’ and the feedback-soaked ’Sulliday’ to the queasy ambient jazz that is ‘Dizzy’ and the slo-mo psych of ‘Spermwhale Trip Over’, the album was an instant hit with the UK music papers. Melody Maker journalist Simon Reynolds called it “the outstanding record of 1988”.

“We didn’t make ’69’ for anybody but ourselves,” declares Rudy. “It was like we had a new toy, this thing called making music, and everything we did stemmed from our desire to get those sounds out.”

Which is perhaps why the press went into spasms trying to convey what the album was like and what made it so special.

“We did often wonder what some of the journalists were on,” grins Rudy. “But at the same time, we totally loved it. And I have to admit that a lot of what they wrote complemented what we were doing, because there weren’t any words to describe some of the sounds we were making. We didn’t realise that to begin with, but we caught on quickly.”

There are numerous references to dreams and sex in the often oblique lyrics of ’69’, two everyday human experiences that involve or induce altered states of consciousness. The sea, that mercurial, immersive and transportive environment that makes up more than 70 per cent of our planet, is another repeated theme.

“We were lumped in with ethereal 4AD artists, but also with groups like Sonic Youth, even though we didn’t look or sound like any of them,” says Rudy. “That’s where the idea of ‘dreampop’ came from. We felt we needed our own way of describing the music and that made sense to us, partly because we were into the idea of lucid dreaming. We’d talked about our dreams for years and tried different techniques to trigger lucid dreaming. After we formed the band, we started dreaming music more and more. A lot of our melodies came out of dreams. We’d wake up and go, ‘Quick, get it onto a cassette’.

“We weren’t averse to chemicals too, although we didn’t sing about that much, apart from ‘Spermwhale Trip Over’. I took LSD experimentally. I’d taken it at a few parties, but I soon realised that wasn’t a good idea. But taking it at home and spending the day listening to my favourite music, doing some yoga, going for a walk in the woods… that was more of the British trip. Alex and I were both into that, we were into acid and yoga and meditation, and I was also into Zen Buddhism. So we knew how you could sit still for half an hour and completely leave your body.

“But while we knew about altered states of consciousness, we knew about the bad side of that as well, which is why ’69’ has a dark edge to it. ‘Dizzy’, for instance, is about having that astral projection experience but not being able to get back into your body again. Then you would feel quite dissociated for a few weeks, like a bad trip kind of thing. We didn’t talk about that sort of stuff explicitly, though, we just tried to express the feeling. So if you think about it from that perspective, we could never have sounded like anybody else. What we were doing was something extremely personal.”

And then there was ‘i’, AR Kane’s second album, which came out in October 1989. With 26 tracks spread across two discs, it both delighted and confounded the critics once more, not least because of its many and varied pop moments. The effortlessly funky ‘A Love From Outer Space’ and the strings and horns-fuelled electro of ’Snow Joke’, for instance.

“After the success of ’69’, Geoff Travis basically said, ‘We’re chucking the kitchen sink at this, so you can do whatever you like now’. It was like we’d been handed the keys to the candy store. We thought, ‘OK, let’s have great studios, top engineers, cool producers…’. There were suddenly no rules. And that was something we were always going to respond well to.”

The album was recorded at some of London’s leading studios, including Blackwing, Orinoco and The Church, places that were worlds away from Alex’s mum’s basement. Bonjo Iyabinghi Noah from African Head Charge and Billy McGee from Marc And The Mambas were among the guests, the latter bringing along other members of Marc Almond’s entourage, including cellist Audrey Riley and violinist Gini Ball. Ray Shulman, who sadly died earlier this year, played a key role on ‘i’ too.

“We had a good time and we probably got a bit self-indulgent,” says Rudy. “I remember we were reading a lot – books on esoteric religions, some sci-fi stuff, the newspapers – and the ideas were flowing constantly. I’d be saying, ‘Let’s try this’, and Alex would come back with, ‘Let’s try that’. And because we had plenty of freedom, we took it as far as we could. Which was exactly the right thing to do.

“When we’d finished, we sat back and thought, ‘What have we got here?’. I’d been reading about how humans basically consist of four components. It was to do with four different brains – a moving brain, an instinctive brain, an intellectual brain and an emotional brain – and each song seemed to fit in with one of those components. So when we arranged the tracks over the four sides of the album, it felt like we’d created a whole person. That’s why we called it ‘i’.”

Typically of AR Kane, they claimed there was also a fifth side to ‘i’, which was dispersed within Side Four.

“We were just playing with the form, you know, this idea of a five-sided four-sided album,” says Rudy. “Listening to it again, it’s a really strong record. It’s maybe not as good as ’69’, not as a complete album, but there aren’t any duds on there.”

And if ’69’ and ‘i’ are radically different beasts, AR Kane were something else again when they played live. They didn’t actually perform many shows – the Setlist website documents just 11 gigs between 1986 and 1989 – but they were untamed and unhinged spectacles, with Alex and Rudy roaming every inch of the stage, their bodies twisted and their eyes wild as they wrestled primeval noises from their guitars. Rudy in particular was a ferocious figure up there. So it seems strange that the pair have been widely cited as a major inspiration for the shoegaze scene.

“I don’t think we ever stood still and stared at our feet,” grins Rudy. “We both did loads of clubbing when we were younger – going out all night and building up a sweat on the dancefloor and losing ourselves in music – and that had a massive impact on us. We’d take a handful of blues, have some spliff, have a couple of rum and cokes, and spend hours just dancing. Even more so after ecstasy came along.

“So when it came to playing live, yeah, we put that into it. There was the rumbling bass and the big waves of feedback and the blood spurting from our fingers as we hit the guitars… that was all part of it for us. It was physical. It was visceral. It was violent. It was a real expression of some very intense feelings. We certainly weren’t fey.”

The third and final AR Kane album, the largely downtempo and melancholic ‘New Clear Child’, came out on David Byrne’s Luaka Bop label in 1994. Alex had moved over to America by this point and Rudy says the tracks were put together by “sending cassettes backwards and forwards across the sea”. It wasn’t a happy experience for either of them. A fourth album was discussed, but the plans were shelved before the recording began.

While Alex Ayuli left the music industry after a couple of solo releases at the turn of the millennium, Rudy Tambala has remained active throughout the last three decades, teaming up with his sister Maggie as Sufi in the 1990s and as Jübl in more recent times. He’s also been an attentive steward of the AR Kane legacy, overseeing compilations and reissues, managing websites and social media accounts, and even resurrecting the name for several live shows with Maggie and guitarist Andy Taylor in the mid-2010s. Jübl developed out of these gigs.

That Rudy still has a lot of love for AR Kane is obvious from his work on the ‘AR Kive’ boxset. Alongside the chunky slices of vinyl, the package includes a superb booklet containing photos, a mini-biography of the band by UK music journalist Neil Kulkarni, and a short story from Rudy. There’s also an essay by the late Greg Tate, the New York writer and activist who co-founded the Black Rock Coalition with Living Colour guitarist Vernon Reid. Tate describes AR Kane as “two dope boyz… who claimed all the hallmarks of Black Alienation, Black Rage, Black Silence, Black Noise and Black Ragga as their sonorous and luminous own”.

“I wanted to include that because we have never told the black side of our story before,” explains Rudy. “At the time, Alex and I always tried to steer clear of the whole question of identity. Any identity. As a matter of fact, Greg and Vernon wrote to us in the late 1980s and said, ‘We want you to join the Black Rock Coalition and lead the movement in Europe’, but we turned them down. We weren’t interested. It didn’t make any sense to us. We didn’t see our music as black. We saw it as music of many colours.

“I guess a lot of it was about us wanting to go against the grain. I mean, we got a negative response from some black people, even getting abused on the street for wearing leather jackets, because that’s not how we were supposed to have dressed. With the benefit of hindsight, though, I’ve come to embrace the idea that we were part of a lineage of creative black artists. And I know we couldn’t possibly have done what we did if we hadn’t been part of that lineage. I also know I’d be naive to ignore the fact that being black in Britain in the 1980s was definitely a thing… but what AR Kane did was definitely a different kind of thing.”

A different kind of thing in every way and on every level. Unorthodox to the core and glorious to the max.

‘AR Kive’ is out on Rocket Girl