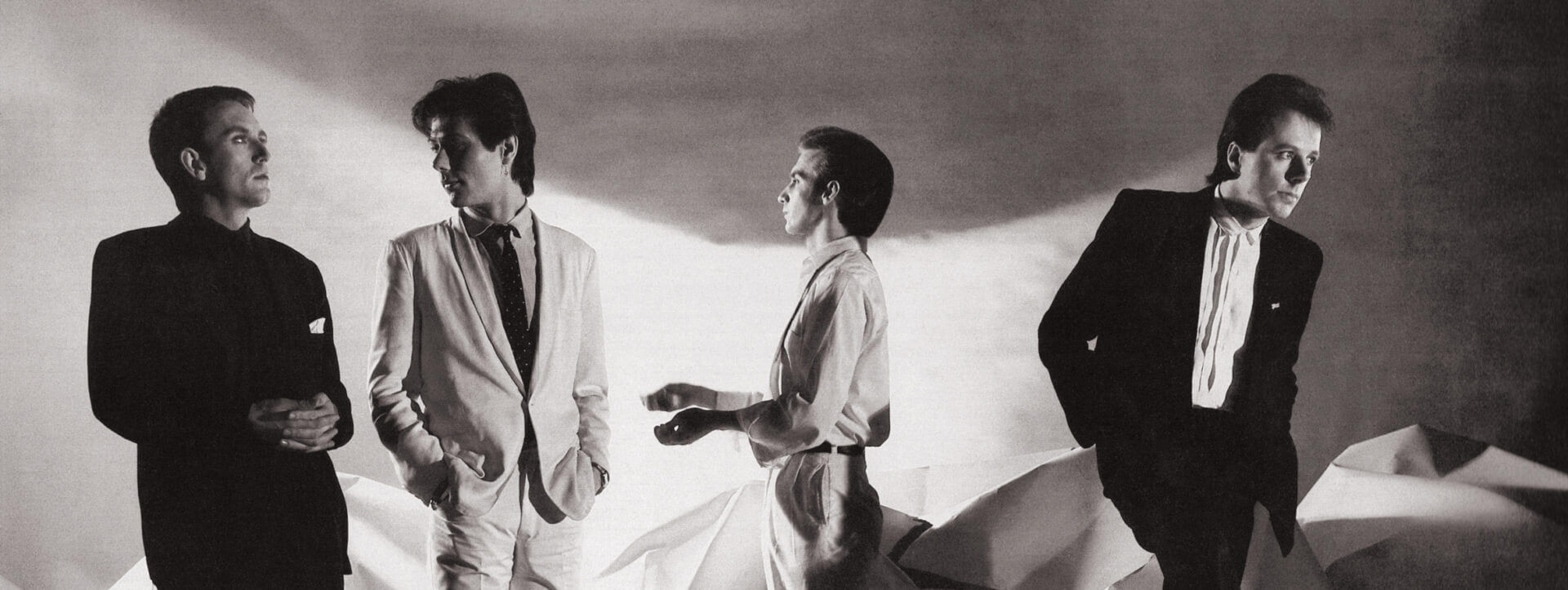

Ultravox’s seminal album ‘Vienna’ took the band from the edge of oblivion to pop stardom. Midge Ure, Billy Currie, Chris Cross and Warren Cann remember the turbulent times and twists of fate that set them on the path to glory

Want to read more?

Sign up to Electronic Sound Premium to gain access to every post, video, special offers, and more. 100%, all you can eat, no commitment, cancel any time.

Already a premium member? Log in here