Drawing on the ultrasonic sounds of the Amazon rainforest, the new album by Australian-Icelandic producer Ben Frost sees him collaging environmental recordings and complex electronics to stunning cinematic effect

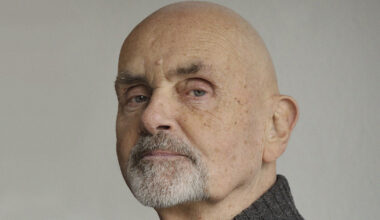

If there’s one thing that Ben Frost is not, it’s nostalgic. The work of the Australian-Icelandic composer, producer, sound designer and musician has always marked him out as future-facing, someone forever seeking fresh perspectives to guard against creative stasis, repetition and his own boredom. Since looking back is not Frost’s way, the suggestion that this year’s 20th anniversary of his debut album, ‘Steel Wound’, constitutes a milestone leaves him momentarily nonplussed.

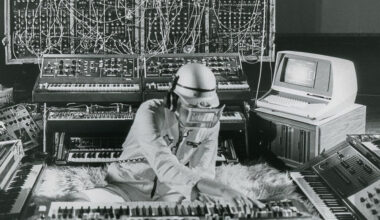

On a bright January morning, as he crunches across the snowy streets of downtown Reykjavík, where he’s lived since 2005, Frost is considering whether his idea of creative satisfaction has changed over those two decades. His method has certainly evolved from being heavily reliant on guitars to admitting strings, brass, prepared piano and harpsichord – and, latterly, making field recordings central to his power-ambient style.

“I don’t feel there’s ever been a moment where I’ve been satisfied – which is probably quite unhealthy,” he decides. “Do you know the American visual artist Matthew Barney? He’s become a dear friend over the years. He began drawing when he was a young man in college, playing football, and his whole process is very much connected to his physical body and sporting life.

“He started a series called ‘Drawing Restraint’, where he’d make physical impositions on his ability to create art. He would nail the piece of paper he was trying to draw on to the ceiling and then construct some kind of climbing-wall situation where he had to hang off one hand to make marks on the page. When you talk about a 20-year span of my work, that’s definitely the kind of image and idea that comes to my mind – ‘How can I keep making this harder for myself?’.”

Why he consciously seeks out difficulty is a question that Frost still can’t properly answer, although he sees it as relating to his methodology.

“It’s partly because the work I do is a learning process, and every kind of learning plateaus. So then it becomes a question of, ‘OK, you’ve reached that point now, so is that it? Or are you going to push it further, push it deeper?’. Wherever that drive comes from, it’s definitely at the core of what I’m doing.”

This constant push for challenge might seem somewhat bloody-minded, but it’s produced some of Frost’s most interesting work, much of which is collaborative. The groundwork for his ‘Aurora’ album of 2014 was laid during a trip to the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) with the conceptual documentary photographer Richard Mosse and cinematographer/artist Trevor Tweeten, who made a video installation about the armed conflict there.

Frost’s 2022 long-player, ‘Broken Spectre’, saw him teaming up with the pair again, recording source sounds in the ravaged Amazon rainforest for both his own album and Mosse’s film of the same name. Currently producing a new solo album, in March he also releases ‘Vakning’, featuring unfiltered field recordings made with Francesco Fabris – more on this shortly – during the eruption of Iceland’s Fagradalsfjall volcano in 2021.

Clearly an explorer of sorts, Frost is keen to push at the boundaries of his own experiences – be they sensory, emotional or existential – in pieces that are characterised by a vivid sense of place, even if those places are often unknowable or alien. His compositions (especially the solo, non-commissioned kind) are full of contrasts – darkness/light, familiarity/strangeness, calm/chaos, monstrousness/beauty – and have an elemental power. Menace looms while danger waits in the wings. He agrees that the creation of environments is a feature of his music, but reckons there’s something more fundamental in play.

“Sound in itself has no physicality, but that it manifests in the physical world has always fascinated me,” he says. “I remember being very, very small and standing next to a very big stereo system, just turning it up and being fascinated by the feeling of this invisible medium that’s somehow manifested in the body. The way it could move objects on the table on the other side of the room and rattle windows… the way it could enact itself on the world.

“I remember reading about Nikola Tesla’s experiments with resonance in school when I was a teenager. He would go to a building site and attach some kind of motorised device to a metal beam and then tune the resonance to the point where this structure – which is made of steel, the foundation of human civilisation at this point – risks bringing the building down, just by defining the resonant frequency and repeating these tones over time. I think all of those ideas play into where my interests go.”

Again, it’s the lure of extremes – for Frost, they’re thrilling and inspirational.

“I’m sure that this could all be worked out with a good psychiatrist,” he laughs. “There’s definitely a kind of attraction, and a big part of what I do has been about eschewing the middle ground, avoiding the comfort zone. And responding to emotional states, seizing upon moments. That’s always been at the heart of it. ‘Steel Wound’ is a record I made 20 years ago, but even today there’s a locality to that music for me – when I hear it, I’m immediately back in the house where I recorded it.

“It was basically my attempt at dealing with the loss of my grandmother, which was my first interaction with death. She was the most important influence in my life as a young man, and I watched her wither away from cancer. ‘Steel Wound’ was written and recorded around and directly after that event, but I don’t believe it was a purposeful move. I think I was too young to process it, but looking back at it now, I can see it is the way it is because of when and where it happened.”

Frost’s output includes a handful of solo albums and numerous film and TV scores, as well as opera and dance projects. It has always been impressive, but lately he’s been on something of a roll. Coming off the back of soundtracking three series of the acclaimed Netflix drama ‘Dark’, he scored ‘1899’ for the same creative team and also released the previously mentioned ‘Broken Spectre’, which he views as bridging the gap between a personal statement and a film soundtrack. It stands in sharp contrast to his revelation in an interview following the release of ‘Aurora’, when he admitted to not knowing whether he had any more records in him. The very opposite has proven to be the case.

“Just after ‘Aurora’, I genuinely felt like maybe I’d said everything I needed to say for now,” he explains. “My reason for making an album needs to be not just putting more music into the world, but rather a feeling of, ‘OK, there’s this thing I’m hearing in my head that I can’t find in someone else’s music, so I need to create it’.

With something like ‘Aurora’, or even going all the way back to ‘Steel Wound’, those records are manifestations of a kind of music I wanted to hear [chuckles]. It’s totally self-indulgent.”

The kinds of places Frost’s works have taken him – coupled with their minimalist, austere, glowering beauty and simmering threat, informed by modern classical music, black metal and ambient, weighted with geo-political and humanitarian meaning – have led to a certain public reading of him. It’s that of a serious-minded, even stern man – a kind of dark lord of asceticism. So let the record show that Ben Frost is a convivial sort who certainly has a sense of humour.

“They should talk to my kids about that,” he says wryly of the misconception. “It’s all because I don’t smile enough in photographs, but it’s kind of true. There is definitely that perception, but the misunderstanding is similar to the fact that some of the most polite, genial and gentle-mannered people in my life are in black metal bands.

“My friends, my bandmates in Swans, Michael Gira… I mean, these are not lords of the ‘dark realm’, like Darth Vader. If there’s a common thread there, it’s that I’m drawn to those spaces. Not because I’m a depressed, stern person but because in the darkness, in those spaces, there’s a lot to learn.”

Of course, there’s also the potential of a different kind of perception connected to Frost’s project choices.

He’s well aware of the issues raised by an artist in search of source sounds visiting the DRC, South America’s Pantanal – the world’s largest tropical wetland, now in danger of devastation from drought, deforestation and dredging – and Lesbos, one of the Greek islands in the spotlight as a result of the refugee crisis.

Of his work for ‘Broken Spectre’ with Mosse and Tweeten, he admits to “knowing how it reads”.

“It’s three white guys going to the Amazon on some kind of exotic holiday,” he says. “The spaces we visited during the time we spent down there are some of the most genuinely horrific environments I’ve ever seen. It’s the front line and it truly is like stepping back in time because you’re seeing a process, a fast-tracked version of what happened all over Europe and throughout the Western Hemisphere 200 years ago.

“You’re watching a developing nation destroy itself because their kids want the same shit on Facebook that our kids want – and it’s horribly depressing to see. When people think of the Amazon, they imagine the sort of pristine, David Attenborough wilderness, and it really is a very skewed version of those realities.”

The upcoming ‘Vakning’ (“awakening” in Icelandic), is a different kind of Ben Frost album. Partnering with Francesco Fabris, who collaborated with Frost on the ‘Dark’ series and is a composer and sound artist in his own right, it’s a set of essentially raw field recordings (with treatment limited just to some very light EQing).

Rather than construct an alternative reality, they document a real-life event – a volcanic eruption. With ‘Vakning’, the pair aren’t artists so much as witnesses who hiked up lava fields – Frost during the day, when scientists, equipment and helicopters were everywhere, Fabris in the dead of night – wearing masks to protect themselves from toxic gases.

The album will be released on Room40, the label started by Lawrence English, a self-described “philosopher of listening” and fellow Australian.

“Lawrence and I have been friends for 25 years, and he’s been a huge influence on me,” says Frost. “He was the first one to really give me a proper introduction to field recording as an idea. It’s something that’s always been on the periphery of what I do, but over the years it’s become clear to me that the more performative aspect is what’s so fascinating about it. I think what I didn’t understand as a younger man – and this is the direct result of doing it for so many years now with Richard Mosse – is how the microphone in these situations is a lens through which you kind of choose your subject.

“More than that, it’s about the performance of listening, of standing in a space and choosing to press record – the stillness and the weird tension required to make a recording that doesn’t require any post-production or hours of laborious, microscopic edits, where it has this uninterrupted, strange realism to it. That, I’ve realised over the years, is a truly, truly difficult thing.”

Ben Frost has never been one for using his art to bang a drum. However, he agrees that Earth’s fragility, the impact we have on the climate and natural environment and the impermanence of human existence are themes that loom increasingly large for him, involving a responsibility that’s hard to deny as the clock ticks.

“I believe there is a moral imperative as an artist at this juncture to kind of start yelling, albeit in a way that’s true to myself, to address the elephant in the room,” he says. “And I don’t see any bigger issue than the damage we’re doing to the climate. That said, I believe some of the greatest atrocities in the history of art have been committed with the best of intentions. So it’s a fine line.

“Maybe the most important thing for me is to continue making work that feels really honest and true to where I am in my process, in my journey – to just keep pushing the envelope so I’m mounting the challenges for myself, in whatever form that takes. I think that’s the job, ultimately, when you’re blessed with all the privileges that I’ve had in my career so far. It doesn’t feel like the time to put my feet up and start taking easy shots. It feels like, ‘OK, now you need to use that’.”

‘Broken Spectre’ is out on The Vinyl Factory. ‘Vakning’ is released by Room40