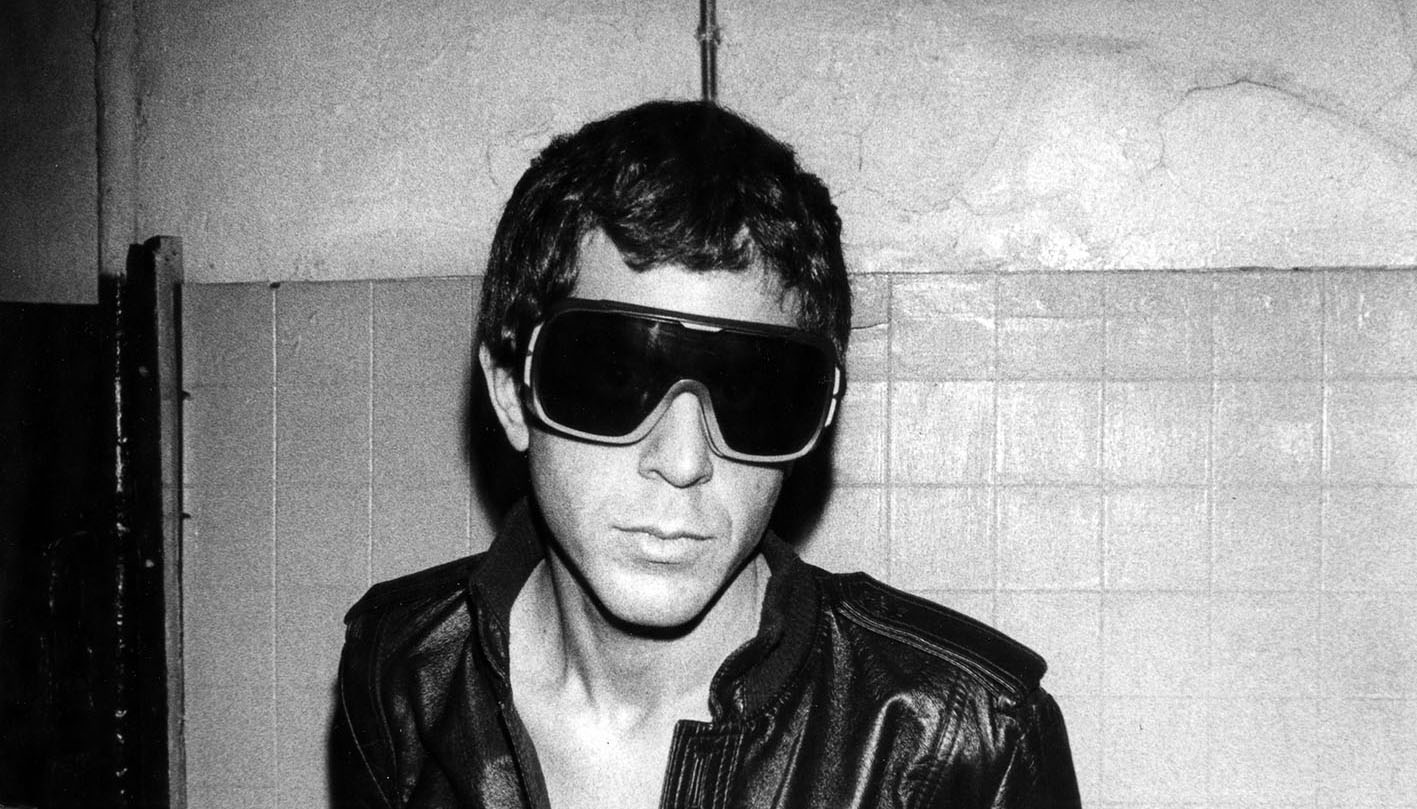

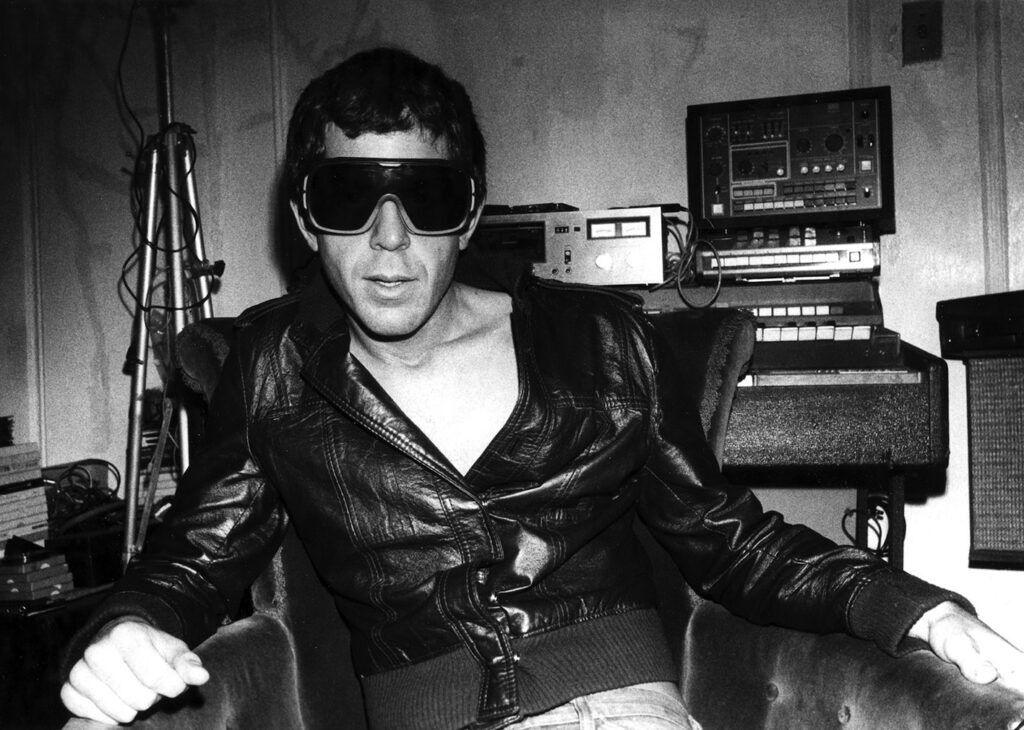

Rooted in fervent, free-form experimentation, Martin Rev’s formative 1970s cassette sonics not only fed into the arch-provocateur’s work with influential New York synth-punksters Suicide, but also his distinctive solo oeuvre. With a new release of archive recordings, he reflects on those gritty early years

‘The Sum Of Our Wounds (Cassette Recordings 1973-85)’ interrupts the systematic reissuing of Martin Rev’s nine-LP solo catalogue by Hamburg label Bureau B, to present a frequently mind-blowing selection from his mountainous archive. On a late September afternoon in New York City, the former Suicide keyboard magus is playing through a test pressing, trying to pinpoint the earliest tracks and the first showings of his Seeburg Rhythm Prince drum machine. Along with Alan Vega’s vocal extrapolations and Rev’s searing circuit rumpus, it’s the third key element in the trailblazing sound that blueprinted so many aspects of electronic music.

Despite having interviewed Rev countless times since Suicide were attracting untold abuse for supporting The Clash 45 years ago, it’s still fascinating (and somewhat surreal) for this long-time fan to hear him rifling through his early sonic sketches, trying to place their creation. On ‘She’s Back’, for instance, the coruscating fanfare of drones and alien greenhouse whizz-bangs swelling to primal catharsis is devoid of any drum machine pulses. Surely it dates from Suicide’s wall-of-sound era before Rev bought his drum machine for $30 from a couple in Queens whose 19-year-old daughter had used it to accompany her poetry.

“They told me she had recently committed suicide,” he recalls.

That was in early 1975, but far from predating it, Rev declares that ‘She’s Back’ is “actually later”, crushing my theory with a chuckle.

“I took on a studio in the early 80s and recorded just using the equipment they had there… but there was no rhythm machine on this one.”

The fizzing loungecore of ‘Yearning’, he says, can be dated to “around the time I just got the machine”.

Still searching for the oldest cut, I mention the primitive woodblock sashay of ‘Skateboard’ conjuring “some kind of electronic Moondog”, which prompts Rev’s memories of seeing the fabled Viking of Sixth Avenue in the 1960s.

“That’s early, and obviously there’s a drum machine… unless I had something before the Suicide drum machine, but I don’t think I did,” he muses. “With some of these, I probably conceived the melody lines in 1973. The cassettes might have been recorded a little after, when I had a machine around.”

Remembering the new set’s title, Rev laughs.

“But what can we do at this point?”

Whenever it was recorded, such was Rev’s uniquely idiosyncratic approach to developing tracks, they all sound like arcane pointers to a distant future in a parallel universe. These blueprints and doodles have nestled in his archive since they were overtaken in the creative process by subsequent versions on studio reel-to-reels.

“The album is actually an idea that Bureau B had a year or two ago,” he explains. “I must have mentioned these cassettes in a conversation, but I wasn’t planning to put them out… or maybe I said we could do it sometime. The reality comes when they ask if they can put them out! They said there was real demand for that kind of stuff. I hear that all the time, like when they wanted us to go back and play early Suicide on the original instruments. There was a trend for that kind of thing, but it didn’t work for me internally to do it. Of course, these tracks were not yet titled when we didn’t have a deal and couldn’t release anything, so I guess they are – as it says – my sketches.”

After Bureau B’s Daniel Jahn, who has steered and annotated Rev’s reissues so far, persisted with the archive idea, it occurred to Rev that these old recordings could also be integrated into the new album he’s been working on for the last few years.

“I started going through my cassettes and digitising them, getting out the best parts and throwing them into the album I’m working on now,” he says. “It was another of those rocket ship propulsion things – another stage going at a different velocity. The day after I told him I was copying them, he gave me such an incredible response that I was blown away. That was the gestation.”

As some tracks were quite lengthy, Rev suggested Jahn edit them down.

“There was a lot of stuff, and I’m working on other things,” he explains. “I don’t want to spend the bulk of my time going back into my own history, which for me is less fascinating than the present. After a while, Daniel said he’d gone through them and it was gonna be incredible. He sent me his choices and sequence, and I could tell he was really into it. It has a thing of its own, like a new album the way it’s sequenced, although I didn’t play anything new. Daniel deserves a lot of credit for his enthusiasm in getting behind it.”

Among the grainy clips and skeletal try-outs, some are recognisable from later manifestations on Suicide records or Rev’s early solo albums. Most startling is ‘Dreams’, a previously unheard instrumental incarnation of Suicide’s timeless ‘Dream Baby Dream’, released on 12-inch in 1979 as a bridge between the debut album and the following year’s glistening ‘Suicide: Alan Vega And Martin Rev’.

“That’s not necessarily the first version of ‘Dream Baby Dream’,” begins Rev as the track’s spirit-hoisting optimism roars behind him. “That’s something I was playing with at home pretty early. I think this is from the early Red Star days. When we were cutting the first album, [Red Star founder] Marty Thau had some extra studio time and still wanted to do some mixing. Alan [Vega] wasn’t going to come in, so I cut this track. As far as the vocal went, the very first was ‘Keep Your Dreams’ before ‘Dream Baby Dream’. We put it on the 45 for the jukebox at Max’s Kansas City – it preceded the ‘Suicide’ album by a year or two – and we convinced Marty we could record actual songs. Later, ‘Dream Baby Dream’ came about in the studio, and Marty hit us up about cutting with Ric Ocasek, because he really wanted to produce us. That’s when we went in for one night and cut ‘Dream Baby Dream’, as it’s known now, with ‘Radiation’ on the back.”

Recorded in the limbo period just before ZE Records and the second Suicide album at Sorcerer Sound on Mercer Street, Rev’s self-titled 1980 first solo album is represented by alternative versions of the guttural bubblegum vocal mutant ‘Baby O Baby’, a xylophone-tickled ‘Temptation’, the tolling bell haze of ‘Asia’, and the joyously sparkling ‘Mari’. The last of these, which opened the original LP, was written in homage to his wife and lifelong muse – and Suicide’s original drummer – who sadly passed away in 2008.

Released on Charles Ball’s Lust/Unlust offshoot Infidelity, Rev says the set “reflects a kind of New York sound and the instrumental possibilities of pure sound I had uncovered through Suicide”.

“There were a lot of mixes of that first album,” he continues. “I’ve got boxes of two-track tapes, including about five of ‘Baby O Baby’, most of them instrumental. I don’t know if anyone wants to hear more versions of ‘Baby O Baby’ and ‘Mari’, but I’m told people love that stuff.”

‘Martin Rev’ is currently lined up for its long-awaited Bureau B reissue. New York Rocker’s Roy Trakin described it on release as “particularly revelatory in capturing the man’s left-field genius”, and it still sounds fearlessly new 43 years later. Suicide’s second LP from 1980 gave Rev the synths and momentum for starting his next solo album, ‘Clouds Of Glory’, in February 1981.

“I had this very clear visual idea for my next two albums,” he explains. “‘Clouds’ was a natural progression from the second Suicide album. I used that Prophet-5 live for a while, which allowed me to get deeper into what could be done with it.”

His main inspiration came from travelling across America, coast-to-coast.

“At the time, Mari and I were based between California and New York,” he remembers. “I took one of those three-day Greyhound bus excursions, which was my chance to see America for the first time. It was incredible going through the deserts in Texas, Mexico and Arizona. I got this feeling of the American landscape I had in my mind as a child but never really saw. This expanse of terrain, landscape and all those new sensations greatly influenced my visual ideas relating to those journeys, using sounds I was getting on the new instruments.

“Marty Thau had extra studio time, and asked if I wanted to make a record with it, which we did until the studio time ran out. Most of everything was recorded, but it wasn’t finalised or mixed – there was more to do. From there, he wanted to get a deal to complete the album in another studio. That took three years. He sold the record to New Rose in France, who gave me an advance, so we went into Blank Tapes and finished it. The guy at New Rose got upset that there were no vocals because they thought it was a second demo before they were recorded, but that was the record they signed.”

The new collection’s full pelt ‘Laredo’ is a pulsing wind-tunnel-in-hell blueprint for ‘Rodeo’ on ‘Clouds Of Glory’, presaging house music’s 4/4 kick drum three years before Jesse Saunders released ‘On And On’. Then there’s the album’s swooning doo-wop instrumental ‘Whisper’, here with Rev’s original and suitably low-key vocals. It could be a prototype for ‘Surrender’, from Suicide’s ‘A Way Of Life’ from 1988, but Rev maintains it’s a separate song in the grand tradition of his beloved doo-wop groups, who often used near-identical melodies. There hangs a tale…

Thau had taken a tape of the instrumental to former New York Dolls singer David Johansen’s place one day as they were buddies (he’d once managed them) and wanted to play it to him.

“I think he wanted to pitch him to do a vocal,” says Rev. “David said he dug the song, and we should call it ‘Whisper’, so Marty told me we had a title and an idea for lyrics that he started speaking to me over the phone. They were close to what I did but based on that idea. I wanted to get that in because I missed adding Marty’s songwriting credit.

“Marty called me after he heard ‘Surrender’ on ‘A Way Of Life’, very upset because he said I’d ripped off ‘Whisper’. I told him they’re both songs I wrote, and if you listen to each one, they’re different from each other. I didn’t rip myself off – but if I did, so what? ‘Surrender’ and ‘Whisper’ are not the same song, but of course they relate to each other. That [doo-wop] world is part of me, so sure it’s gonna come out.”

After this initially reluctant but ultimately rewarding dip into his past, Rev continues to work on the new album that’s occupied him since 2017’s ‘Demolition 9’.

“The light’s starting to come through what it really is for me in its entirety,” he says.

The set may even surface around the time that Rev’s ‘New York Music City’ biography, which I’ll be writing, appears next year. Meanwhile, ‘The Sum Of Our Wounds’ can only keep devotees of his never-ending musical journey – and Suicide’s towering legacy – on their toes and, in my case, on the trail of that drum machine. It’s still touching to hear Rev’s initial reason for considering electronic drums – he couldn’t contemplate replacing Mari with another human as Suicide’s drummer.

“No way I was going to replace her!” affirms the amiable Rev with a laugh. “I had to go home and wouldn’t be able to face her. Not that she was counting on that so much anyway, as she had plenty to do. It just didn’t feel right. I got this vision when I was walking around and remembered drum machines, so the reason then became musical. I heard the spatial aspect and a whole different dynamic. At that point, I was still doing tracks like ‘Rocket USA’ and ‘Cheree’ without any drums. When I put the machine in, it felt like we had something… this electronic world was so incredible.”

‘The Sum Of Our Wounds (Cassette Recordings 1973-85)’ is out on Bureau B