The healing power of sound waves, or Radionics, is as fascinating as it is bonkers. The wild and wonderful machines built by Oxford-based scientist George De La Warr were never intended as instruments, but they went on to inspire electronic pioneer Daphne Oram. We meet researcher and musician Daniel Wilson who tells us De La Warr’s incredible tale…

“If you got faults, defects or shortcomings, you know, like arthritis, rheumatism or migraines, whatever part of your body it is, I want you to lay it on your radio. Let the vibes flow through. Funk not only moves, it can remove, dig?”

In Parliament’s famous 1975 song ‘P Funk (Wants To Get Funked Up)’, George Clinton delivers a monologue praising the unusual powers of his form of music. In a manner of speaking, he was praising radionics.

Sincere or not, Clinton was talking about the healing power of sound waves, the ability for certain frequencies to cure illnesses. It’s a weird enough notion for a sci-fi obsessed troupe of funk musicians, but the idea that radionics, an arcane branch of pseudoscience, could help heal the sick was studied, experimented with and believed in by a number of respected scientists in the first half of the 20th century. Increasingly it seems there’s a new wave of radionics freaks out there as internet groups have sprung up and the field has become an area of fascination for modern musicians and scholars.

Radionics’ highest profile visionary was the American Albert Abrams, who made a packet in the early decades of the 1900s by creating sonic machines he claimed could cure illnesses. The San Franciscan considered electrons to be the foundation of life, and his core principle, Electronic Reactions of Abrams (ERA), would power a series of very expensive devices he made, known variously as the Dynomizer, Oscilloclast and Radioclast.

While his earlier machines could, he claimed, diagnose any illness from a drop of blood, or someone’s handwriting (or even their voice from a phone call), his later gadgets could supposedly “attack” the maladies at source with sound frequencies. He sold over 3,000 devices, but curiously the new owners were instructed to never open the units.

That radionics was viewed suspiciously by medical bodies in the States and was eventually completely discredited, with Abrams proclaimed a quack of the highest order, isn’t especially surprising. But far from being shut down, radionics enjoyed a resurgence that brought about a fascinating development.

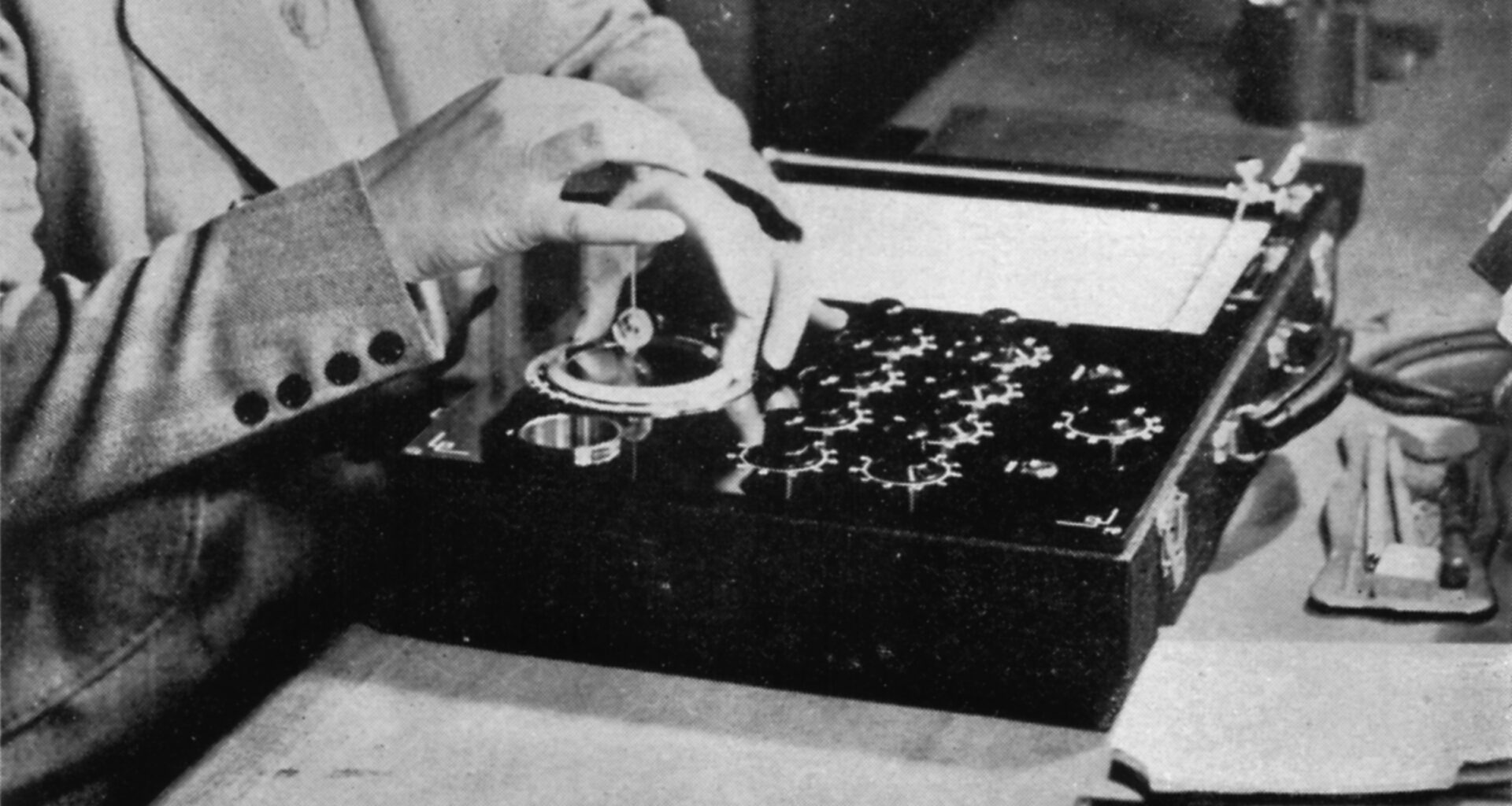

In the 1940s, a scientist in England called George De La Warr would take Abrams’ ideas much further into the realms of experimental electronic sound. At his De La Warr Laboratories in Oxford he began to create a set of machines that it was claimed, through rubber touch pads could detect human thought “frequencies” in order to diagnose illness. The principle was similar to that of water divining or dowsing in that when the user felt a friction in the rubber pad, it indicated a resonance between thought and matter.

One device in particular which was produced by the laboratories, the Multi Oscillator, created electronic music of a kind, though it was designed for health benefits. De La Warr never considered his work to be musical, but this truly bizarre “synth” was rediscovered by musician, scholar and broadcaster Daniel Wilson when he began researching De La Warr in relation to Radiophonic Workshop alumna and electronic music pioneer Daphne Oram.

“The radionics project grew from my time at Goldsmiths University’s Daphne Oram archive,” explains Wilson.

“The archive originally came from my old tutor, [composer] Hugh Davies who died in 2005. When the archive arrived at Goldsmiths it was in a complete mess, so I was roped in to catalogue and sort it into boxes. Which is when I discovered Daphne Oram’s interest in the esoteric field and in the very new age ideas of wave phenomena, the waves that underpin our lives. She was into everything to do with waves, vibrations, electronic sound, music, the ways you can interact with the body, even ley lines. It’s all very strange.”

Within these reams of occult ephemera (including materials about “archaeoacoustics”, the idea of megalithic structures such as Stonehenge being used as huge sound dispersal resonators), Wilson found a pamphlet from De La Warr Labs tucked away. He had been aware of the pioneering, oddball laboratory since his youth, where he read about it in a Readers’ Digest book called ‘Strange Talents’. However, there was far more detail to be unearthed in Oram’s archive.

“The stuff in the archive,” says Wilson, “explained that De La Warr was trying to create a physical basis for radionics by using electronic sound-making gadgets, oscillators, to represent thoughts, concepts, or ailments as actual physical audio frequencies that you can hear.”

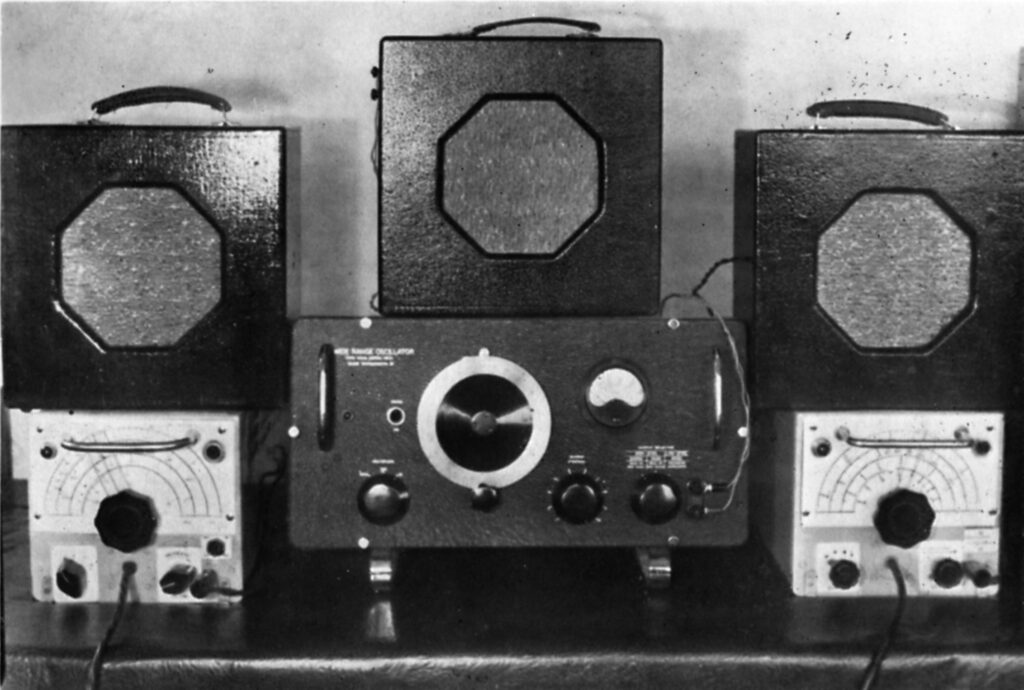

The prototype synth that so fascinated Wilson was designed on the back of earlier electronic sound transmitting units De La Warr had created as far back as 1949. The Multi Oscillator though, had properties of its own which made it resemble an early avant-garde musical instrument.

“I think the first fully integrated Multi Oscillator came about in 1962,” says Wilson. “Before that you just had the three oscillator boxes, which weren’t integrated into any unit. The Multi Oscillator was unique, it was something that the Laboratories built themselves, which housed all the oscillators and amplifiers, with a loudspeaker in the front, and a tape transport control so you could control the overdubbing for even more frequencies. You could create huge clusters of frequencies. It predates Stockhausen’s inharmonic clusters of tones, or La Monte Young’s long duration drone experiments in New York in the 60s.”

Unable to find an actual Multi Oscillator as they’d long been broken up for parts or destroyed, Wilson decided to conduct an experimental music project, based on the principles of radionics and the functions of the obscure synth. ‘Radionics Radio’ was a radio show that Wilson broadcast on Resonance FM. Via an app designed for him by a coder friend, he set about requesting listeners’ thoughts and sound frequencies that he would then transform into music.

“Every week I was harvesting the submissions that would come in from the app,” he says.

“There was a real variety of users. It wasn’t just the Resonance FM listeners. I could tell the suggestions coming in from them, they were quite playful, abstract. One was quite a weird though, ‘Lee Evans’ 1990s Comedy Career’. I made frequencies for that. But then there were radionics aficionados coming in from around the world, who were presumably finding the app through Google, or it was circulated on their forums. The number of genuine radionics people using the app outnumbered the Resonance listeners actually. There ended up being about 2,000 frequencies submitted.”

Users would enter their thoughts and then select frequencies with the trackpad on their smartphones or tablets. “When you feel the slight stick on the track pad, you click and that would store the frequency in a list,” says Wilson. This would become the basis for his recently released ‘Radionics Radio’ album, where he channels the thoughts and corresponding frequencies into music. In places it resembles Aphex Twin or Squarepusher in playful mood. Spectacularly weird, in other words, but wonderful.

“I’d break the frequencies down into scales or use them together, as bell-like tones,” notes Wilson. “I did try to hark back to the electronic music concepts or grounding in the 1960s, using a multi-track tape to give a more saturated tone. They sound older than they are, but they’re digital productions really, which have been muddied through reverbs.”

In the process of his experimental music project based on De La Warr’s ideas, not only did he discover that, far from being a dead science, radionics still has a cult following around the world, but he found that some people take it very seriously indeed.

“I was amazed to see how much interest there still is in radionics,” explains Wilson. “The internet has a role to play in this, in that it can rekindle movements by grouping like-minded people together, so you’ve got all these close-knit radionics communities that I never knew about until I did the app.

“I had a lot of correspondence with people who were asking my motives, whether I was diffusing everything in an antiseptic chamber, had I washed my hands before doing the broadcasting…”

One irate radionics guru even attempted to slur Wilson and his free radionics-related app, worried it would damage sales of his own software.

“He saw Radionics Radio as a threat because it was free to use, so he rubbished it,” says Wilson. “It was animosity from the true radionics programmers that saw it as a threat to their own software, which cost a lot of money. That was quite funny. But I didn’t want to trespass, I didn’t want to upset people.”

Though not able to vouch for the veracity of Albert Abrams’ miraculous claims of electronic sound frequency healing, Wilson strongly believes that the De La Warr Labs scientists were dedicated to radionics and thought what they were doing would benefit mankind.

“I’ve got a lot of tapes that were kindly sent to me by Del La Warr’s daughter, Diana Di Pinto,” says Wilson.

“They arrived with all the tapes unspooled, like an ostrich’s nest in a box. I spent days re-spooling them.

Listening to his voice and the minutes of their meetings, you realise that all these people sincerely believed in it. They were trying everything, persistently experimenting with all these different possibilities.”

As to Wilson’s own perspective on radionics, it’s something he was duty-bound to keep to himself during the collation of frequencies for his ‘Radionics Radio’ project, but he’s happy to offer his thoughts now. Put simply, the jury’s out.

“I don’t want to demolish their sincerely held beliefs in the power of the mind,” he says, carefully. “What I don’t agree with is when you start neglecting proper medicine. A lot of radionics people do stress that it’s a complementary medicine, to be used along with traditional medicine. Noel Edmonds was recently chastised with his claim on Twitter that this electromagnetic device could cure cancer. It’s quite irresponsible because it’s saying, ‘Neglect tried and tested therapies for this highly spurious alternative’.”

Whatever the truth, it’s something that continues to fascinate those who delve deeper into the idea. And if “letting the vibes flow through” has a positive effect, then that can only be a useful – supplementary – thing.

“My own theory is that I find it a really interesting niche, and I hope people have fun with it,” concludes Wilson. “If it brings them help, good.”

‘Radionic Radio – An Album Of Musical Radionic Thought-Frequencies’ is out on Sub Rosa