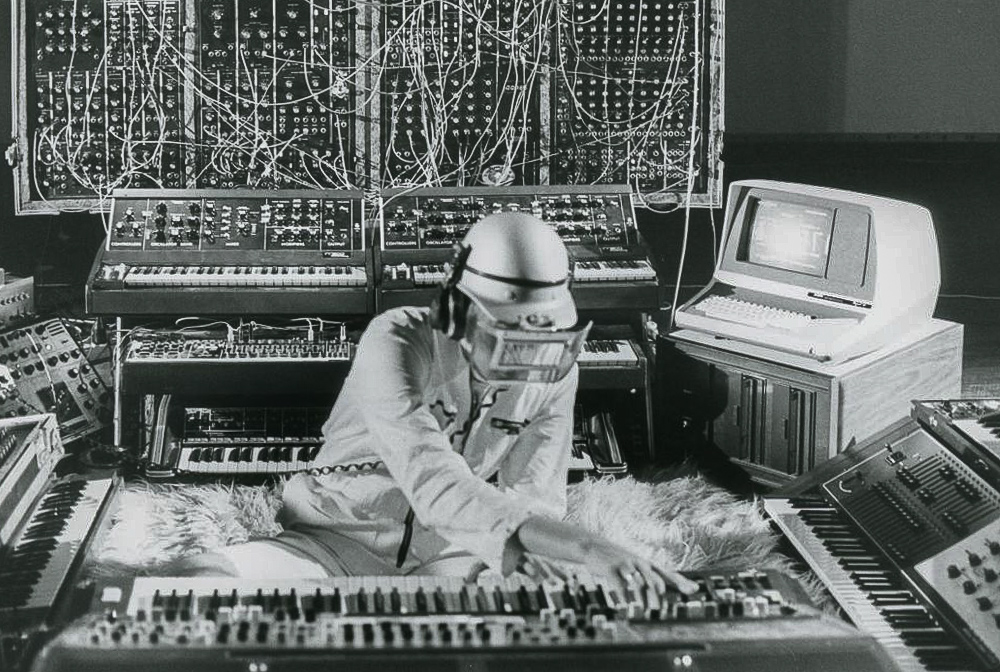

In this final UK interview before his recent passing, the hugely influential German electronicist Klaus Schulze reflects on his time with Tangerine Dream and Ash Ra Tempel and discusses the lingering influence of the sci-fi classic ‘Dune’ – as heard on his new album, ‘Deus Arrakis’

Want to read more?

Sign up to Electronic Sound Premium to gain access to every post, video, special offers, and more. 100%, all you can eat, no commitment, cancel any time.

Already a premium member? Log in here