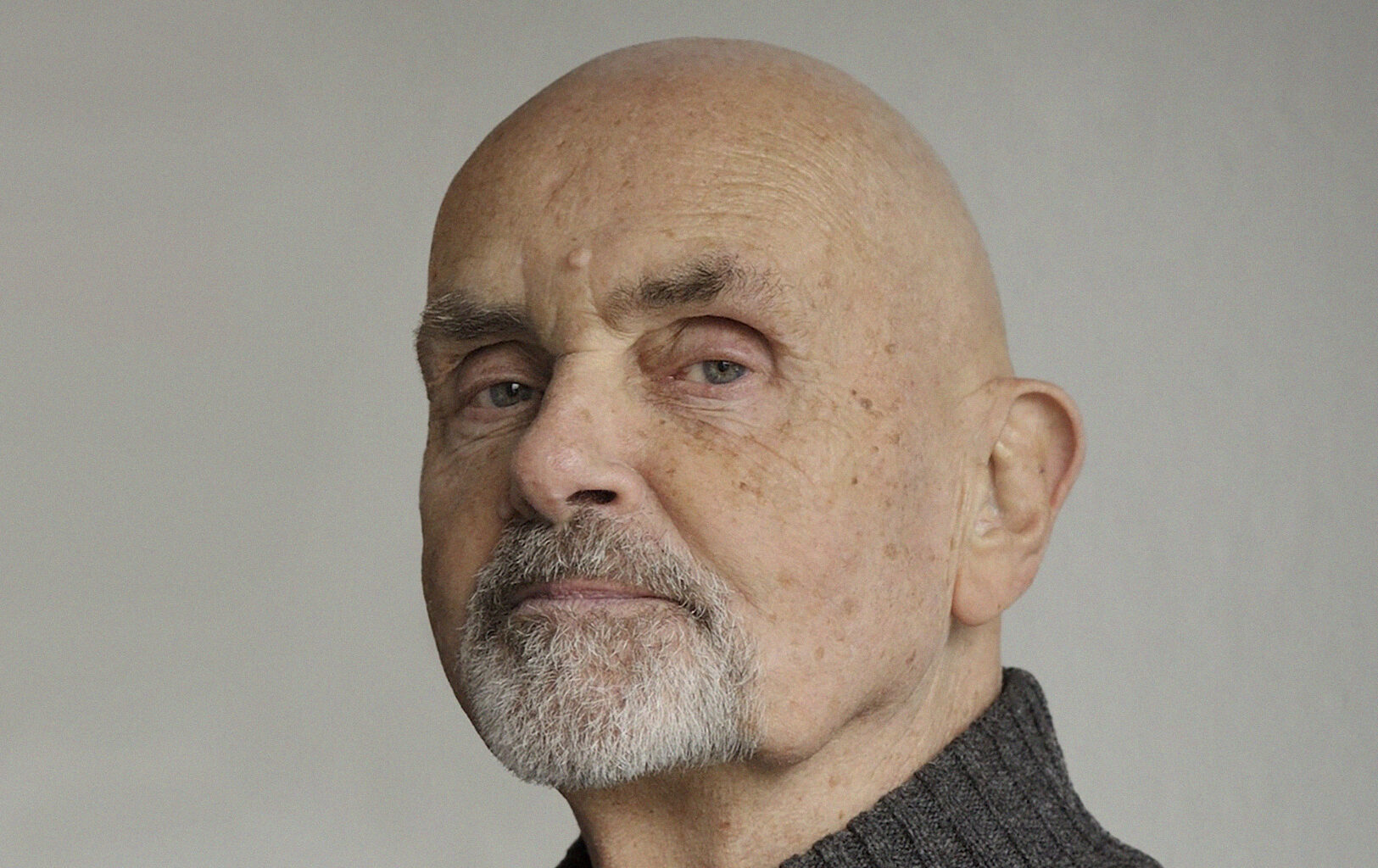

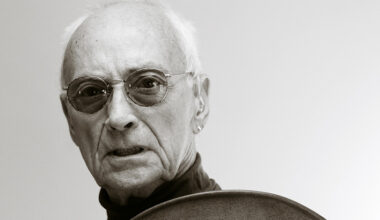

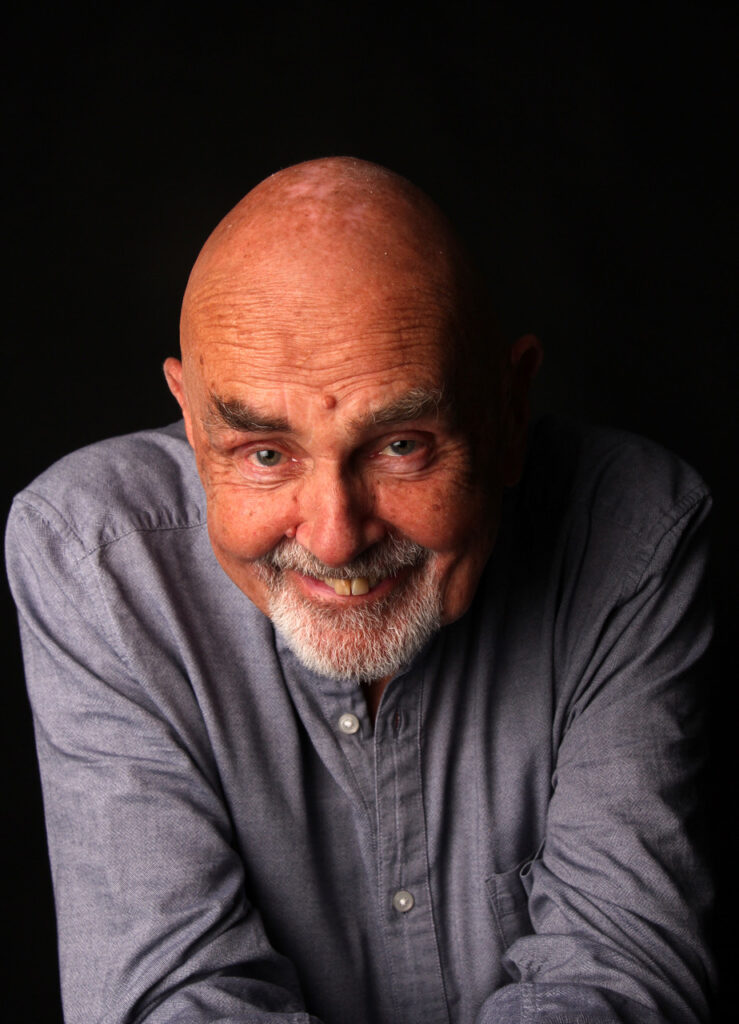

German electronic colossus Hans-Joachim Roedelius reflects on the latest volume of his four-decade ‘Selbstportrait’ series of albums, his turbulent early life, and the love of a good woman

“Time isn’t linear, it’s elastic,” writes Brian Eno in the foreword to ‘Roedelius – The Book’, the recently published autobiography of one of Germany’s seminal electronic pioneers. “There are whole years of my life I can hardly recall and that seem to have passed in seconds – and then there are days and weeks that seemed to last for years.”

Eno adds that the relatively short time he spent recording with Hans-Joachim Roedelius was a “rich and colourful period”. When he was writing down these thoughts, he was no doubt conscious that the same elasticity can be applied to Roedelius’ music.

Listening to ‘Wahre Liebe’, the latest edition of his ‘Selbstportrait’ series, can easily bring home a sense of time stretching, contingent on your level of attention. To only half listen, may cause the sound to melt away so that you barely even notice it. Listen intently, on the other hand, and worlds of possibilities will open up, particularly on the final track, ‘Aus Weiter Ferne’, which clocks in at nearly 15 minutes. In deep absorption, you can dispense with clock time altogether. ‘Selbstportrait Wahre Liebe’ is Roedelius’ first “self portrait” album since 2002 and the ninth in a loose series of sonic self-examinations dating back to 1979.

“Yes, there have been nine,” says Roedelius on a video call from his home in Baden bei Wien, Austria. “But there were a lot of albums that could have been called ‘Selbstportrait’ that weren’t.”

It was Gunther Buskies, head of the Hamburg electronic label Bureau B, who suggested dusting down the same equipment from the original ‘Selbstportrait’ – a Farfisa organ, a Rhodes piano, an analogue drum machine, and a tape delay – to make this new record.

“I think it was a good idea,” says Roedelius. “It meant I could delve back into my past to do it again with what I used at the time. It worked out nicely!”

So was it challenging using gear that is no longer state-of-the-art?

“I think it was rather easy,” he replies jovially. “I was really astonished that it worked so well.”

‘Wahre Liebe’ was recorded with the help of Roedelius’ Qluster bandmate Onnen Bock.

“Onnen bought the machines and he was also the producer of the record. I worked in his studio. I can’t use my own composition programmes now, because I’m too old to manage the necessities. Mostly when I’m working at home or anywhere, I’m with someone else who can help me. I need some help to do what I want to do.”

Bock also provided some of the musical ideas and worked with Roedelius to develop others.

“It’s not only my music. With the melodies, and especially production-wise, Onnen did a lot. It’s beautiful as it is.”

In the four decades since the first of his ‘Selbstportrait’ records was made, Roedelius says the main change in electronic music has been the ease with which it can be operated now.

“You can press a button and you don’t have to assemble loads of equipment to do it live. A laptop and an iPad. It’s easy. When I’m going on tour now, I’m concentrating on piano. I’m not really concentrating on electronic music.”

Roedelius is a laconic interviewee, although that’s not to say the 85-year-old musician is not friendly or inspiring company. When I initially call on the phone, he first scolds me for pronouncing his name incorrectly – I say Joachim with a hard J, when a Y sound is required. Nobody, except his mother and David Bowie, ever called him Hans. He insists that I call him back via a video link.

“I want to see your face!” he says, emphatically.

After several minutes of fiddling around, we finally find ourselves digitally mano a mano with a visual connection established. I’m glad that he insists on this personal touch. We’re still separated by hundreds of miles, but to see the way his face contorts with pleasure when he finds something funny is a treat I could have easily missed out on.

Since 1973, Roedelius has used a limewood sculpture of himself as an emblem. It acts as a visual motif for his album covers and he keeps it close, showing it to me while we chat. It looks like an Easter Island Moai, but in real life it’s tiny, like William Blake’s ‘The Ancient Of Days’, a miniature piece that exudes power.

“It’s not after the Moai,” he says. “It was just a piece of wood that I had left over from refurbishing the old house where we were living. There was always wood – it was autumn, I think – and I fiddled around and made this little head. It’s become my trademark. The ears are behind. Looking forwards, listening backwards.”

Roedelius laughs his way through the interview, sometimes at rather inappropriate moments and usually wholeheartedly. He’s full of energy and mischief, putting men half his age to shame (well, OK, me). But then he has always been industrious. Achim, as his friends call him, has released around 50 albums under his own name since he started recording as a solo artist in the late 1970s, and many more than 50 with his bands from 1970 onwards (Kluster, Cluster, Harmonia, and Qluster) and in collaboration with individuals (Lloyd Cole, Richard Barbieri, and US composer Tim Story).

‘Wahre Liebe’, or ‘True Love’ in English, is dedicated to his wife, Christine Martha, who he says saved him from himself, pulling him from what he describes in his book as his “marginal years”. She knocked on his door one day in 1974 and their lives changed forever. This was in Forst, Cluster/Harmonia’s bucolic Lower Saxony idyll, an artist’s lair and collective living space that Roedelius, Moebius and Michael Rother would literally put on the map.

Roedelius’ life can be broadly divided into two periods – before Christine Martha and after Christine Martha. Or perhaps more pertinently to this article, before Austria and after Austria. Roedelius fled Forst with his wife and their baby in 1978 and they’ve been living in the small spa town of Baden bei Wien, a few miles south-west of Vienna, ever since. The original ‘Selbstportrait’ was the first album he committed to tape in his new adopted country and, as an exercise in self-reflection, it connects the two places in a psychogeographic sense.

“We moved from Forst to Austria in 1978 and, yes, it’s a mixture of the two. I think I had some recordings which I had started working on when I landed in Austria, making it a little bit of a mix of both places. It is a record about Austria with the atmosphere of Forst.”

Why did he leave Forst in such a hurry?

“There was this nuclear plant nearby and children in the area had died of cancer. We’d just had our child, so we had to go because she was in danger.”

The dash to Austria was the culmination of Roedelius’ dramatic and tumultuous life up to that point, whereas the four decades since then, during which time he has created countless solo works of introspection, seem like the very embodiment of serenity.

Hans-Joachim Roedelius was born in Berlin in 1934. A child actor, whose father was a dentist to the stars during the years of the Third Reich, the young Roedelius was asked to take part in a Nazi propaganda film at the age of six. He had little choice but to join the Hitler Youth during World War II.

His family were evacuated to East Prussia as the Allies laid siege to Berlin and they settled there when the war ended, in what became the German Democratic Republic. Roedelius defected to the West when he was old enough but, unable to make ends meet, he returned to East Germany, where he was arrested by the Stasi and sentenced to five years’ imprisonment. Feigning penitence and undying loyalty to the GDR, he was out in two years, but he defected again and never looked back. Soon afterwards, in 1961, the Berlin Wall went up.

I wonder if that time in detention had a bearing on Roedelius’ later music, given the many months he had to spend in his own head?

“I’m not sure, but I do think everything you do in life reflects in your head,” he says. “So, yeah, of course, there’s bound to be a little bit of those feelings, and how I was at the time, in my music. And how I had to behave in prison…”

He pauses for thought.

“… because it was not really funny.”

And then, despite the lack of comedy that incarceration brings, Roedelius laughs anyway.

Back in Berlin, he found work as a physiotherapist and a masseur, the latter job taking him to Paris in the late 1960s. While his father had fixed the teeth of the Reichsfilmkammer, Roedelius was cracking backs for high ranking fonctionnaires at the Élysée Palace in 1968.

“It was a strange period in my life,” he says, not laughing now. “I was a masseur to the wife of the President of the National Assembly! The 1968 student uprising occurred while I was there.”

Did his time in the French capital have an effect on him, or instil in him a sense of possibility, given that he and Conrad Schnitzler set up the bohemian Zodiak Free Arts Lab back in Berlin several months later? Roedelius isn’t so sure.

“I mean, for me, coming from the communist system in the East, the beginning of a new life was really when I moved over to West Berlin. That was long before we started doing what we did.”

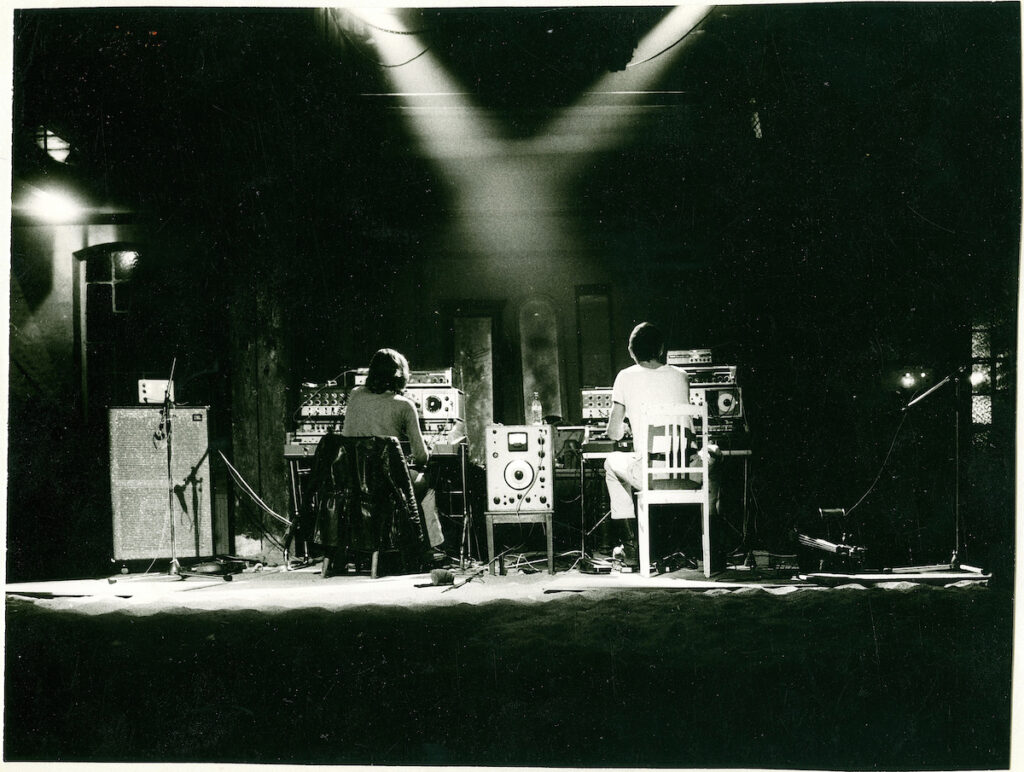

By “what we did”, Roedelius means as Kluster (with Schnitzler and Dieter Moebius), then as the anglicised Cluster (with Moebius), and then as Harmonia (with Moebius and Michael Rother), as well those legendary records with Eno. Each partnership anticipated the future. They helped change the way we think about music and, free from the caprices of market forces, how it is played.

The contribution of these musicians to electronic, kosmische and ambient music cannot be overstated. They’re all cornerstones of krautrock too, despite sounding very different to their peers. Was the initial sound, so streamlined and minimal – and even liminal – a reaction to the omnipresent schlager music that dominated German pop at the time?

“No reaction at all,” says Roedelius. “It was my aim.”

When he met his wife, something changed. Until then, Roedelius had led an alcohol-fuelled, promiscuous lifestyle that, by his own admission, didn’t bring him happiness. What does he think would have happened had he carried on the way he was going before Christine Martha came along?

“I don’t know,” he says. “I was on my way to the monastery because I had given up hope that I would meet my life partner. If she wouldn’t have been there, then I don’t know what I would have done. Perhaps I would have been a masseur in a wellness centre.”

Still drinking?

“Oh yes, drinking and smoking and taking other stuff,” he says with a roar.

Having been a heavy drinker as a teenager and carried his love of booze through to his 40s, did he need treatment?

“No, no, no, treatment wasn’t necessary, it wasn’t that bad,” he insists. “My wife came to save my soul and it worked. The result is my music, my art, my poetry. Without her, it wouldn’t have been possible to do it. It was not easy, of course. If you drink for a long time, you get used to it. My wife got me out of the damp.”

Roedelius calls ‘Selbstportrait Wahre Liebe’ another page of his diary, and these pages all follow back to the first edition in 1979. When I ask why he started this series, he says, rather elliptically, “Because I wanted it”. So was there a modus operandi?

“They were created with just what was coming out of the moment. That was the modus of Kluster from the beginning as well. I think it works. It’s the best system, to play in and of the moment. In the now.”

Is Roedelius a meditator?

“No, not at all, what I’m doing is meditation, it’s what I’ve been doing anyway my whole life,” he says, with another hearty laugh. “Meditating through life and leaving some music, some poetry, some writing…”

There has been an abundance of Roedelius music and there will be more. Tim Story has recently been over to his place in Austria, attempting to digitise over 200,000 kilometres of magnetic tape Roedelius has accumulated over the years. Is he something of a hoarder, then? He laughs uproariously and admits that this is the case.

“Tim came to my house for three months to transfer it. That’s a lot of source tape. I think there are two or three hard discs with digital stuff on there now. From those tapes, at least 10 per cent of it is already overviewed, and Tim just digitised 30 or 40 eight-track tapes. But there’s material still waiting to be released from that side as well. The other 100,000 kilometres is still waiting to be looked at…”

Tim Story is also planning to get Roedelius on the road, playing the ‘Selbstportrait’ albums live for the very first time. This will be partly to promote the English language version of ‘The Book’, translated from the German ‘Roedelius – Das Buch’.

“For me, it’s a challenge, because I don’t know how they’re going to do it and I don’t know what they’re going to give to me. Until now, I’ve been playing mainly piano with some electronic parts. But I think they’re right to push me. I should do my stuff in a way that people can appreciate it. They’ll appreciate what I did in the past, so I should give them some help to remember.”

Right now, as we’re confined to our homes hoping a malicious virus will eventually dissipate, we probably need Roedelius’ time-stretching music more than ever. Sadly, his prognosis for humanity and the future isn’t great.

“I’m not very hopeful that things are going to get better. I think we’re going to get killed by nature because we’re so stupid. We have this coronavirus and I think that’s a bad sign. We can change our minds, but we are destroying nature. Nature will react to us, nature will get rid of us, in order to produce again.”

He laughs once more, but he’s also deadly serious.

‘Selbstportrait Wahre Liebe’ and ‘Tape Archive Essence 1973-1978’, a reissue of the 2014 “audio sketchbook” compilation, are on Bureau B. ‘Roedelius – The Book’ is published by Curious Music