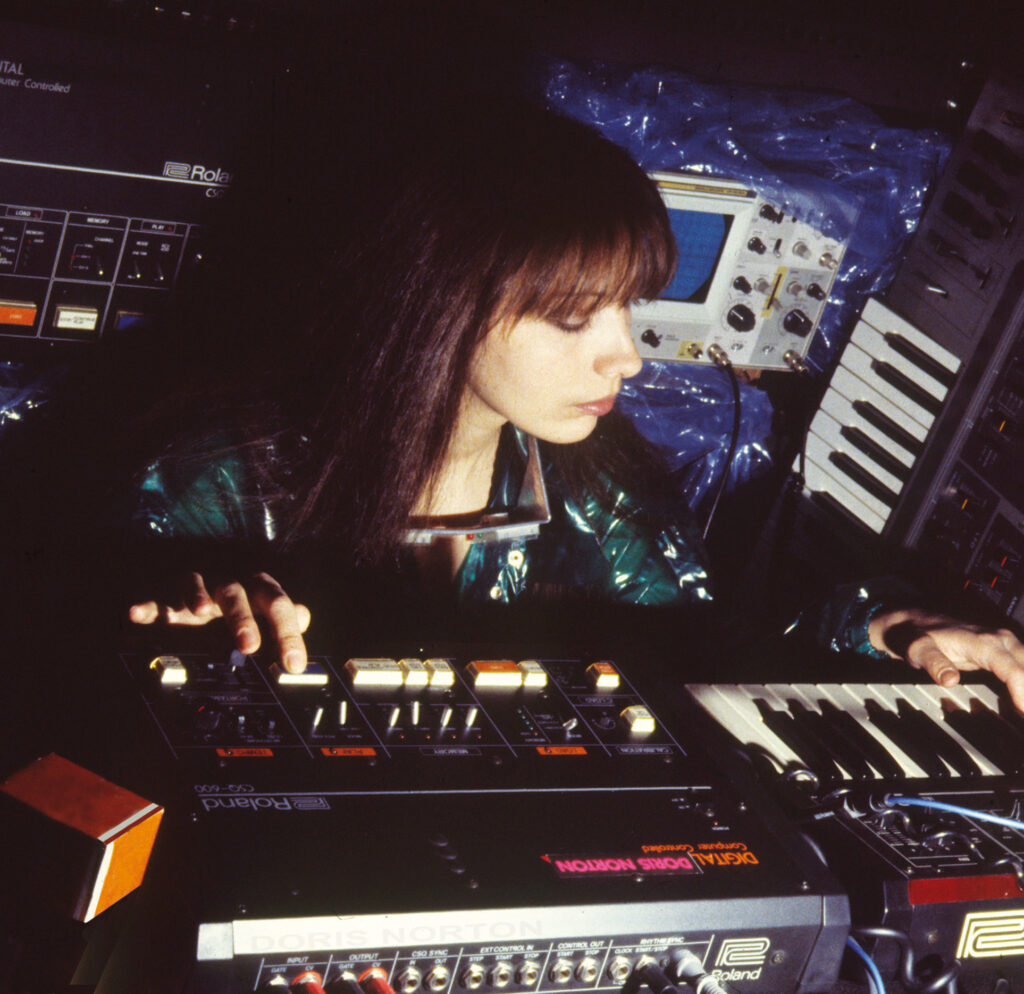

A true electronic pioneer, Italian composer Doris Norton tells us about her prog rock beginnings, Apple-sponsored early solo work, IBM experiments and 90s dancefloor bangers…

“Great artists are a fact throughout history, but because getting in the game is hard, the destiny of too many is to remain in the shadows, but optimism must never die. There is always someone standing out from the crowd”.

These are the apt, but somewhat ironic words of Doris Norton, a pioneer of computer-based composition and electronic music about who there is surprisingly little information despite the considerable critical recognition she has achieved throughout a career that spans six decades. Italian by birth, her first creative venture was as part of late-60s prog rock outfit, Jacula, whose gothic output manifested itself with cathedral-sized organs and a near classical sense of scale. Alongside the guitar of her husband Antonio Bartoccetti and the church organ of Charles Tiring, Norton provided vocals and keyboard on early albums including 1969’s ‘In Cauda Semper Stat Venenum’ and ‘Tardo Pede In Magiam Versus’ in 1972.

“The band never broke up” she says, “I’ve continued collaborating with the founder and leader, there was never a state of inactivity. I composed many tracks, some of them were released, many others are still in the attic, stored on floppy disks.”

She can trace these prog rock leanings to her upbringing, with an early musical experience that shaped outlook.

“My most vivid early memory, when I was about five or six years old, was seeing a performance of Verdi’s ‘Il Trovatore’ at an Italian theatre. During my childhood I loved medieval, Renaissance and Baroque music – Vivaldi, Handel, Rossini and Paganini, but I’ve always preferred to use electronics than to play classical instruments. I was never interested in reading a musical score. If you’re a piano player and want to be technically proficient, you must play the piano every day for hours. I prefer doing something more creative and rewarding.”

Aside from her vibrant use of melodic motif and a sense of energy that rolls through her sounds, one common aspect of her solo work is a sense that, via the exploration of these sonic tools, she is constantly examining the human experience. In 1980, she found herself working with several companies at the cutting edge of music technology…

“It was a very interesting time” she says, “I collaborated not only with Roland, but Apple and IBM too. I got into licensing deals and many of my never-issued experimental tracks were chosen for commercial jingles.”

While some of the tones and textures on her first solo album 1980’s electronic opera ‘Under Ground’ (which carried the now-famous Apple logo) are unmistakably of the time, synth lines dance above ecstatic beats and create an electronic type of pop that retains its impact. And it’s this spirit of experimentalism that seems symbolic of Norton’s outlook more generally. By embracing these ever-progressing frontiers of equipment, she never used technology for its own sake or fetishised the equipment itself.

“We live, I think, in a metaphysical web of chances and circumstances,” she explains. “I thank my metaphysical web, but also I know that “audentes fortuna iuvat” [fortune favours the brave].

In late 1984, Norton was in contact with IBM and she began a collaboration that would lead to her 1986 album, ‘Automatic Feeling’, which used IBM AT, or ‘Advanced Technologies’, which was at the very forefront of computing at the time,enabling her to surf a technological wave that would keep her at the creative vanguard.

Norton thrived on this progressive influence and used it to push the boundaries of her creativity.

“I like to use the same equipment for years and years,” she says, “but I own the Musik Research recording studio with my son [Anthony Bartoccetti, the techno producer Rexanthony] and he changes the studio set-up as technology changes, so I have to adapt myself to the new gear. I don’t like to use musical instruments conventionally. To experiment with their potential is a fulfilling experience. Maybe it’s possible to be one step ahead of time, going against the stream, beyond the conventional rules.”

In 1981, Norton released ‘Parapsycho’ and ‘Raptus’, two albums that, while similar to previous releases, focused on a very specific exploration of the sound. They were still brimming with energy and hooks, but there was a more complex type of electronic pop at work.

“‘Parapsycho’ and ‘Raptus’ were inspired by research into how music has control over physical and psychological health and how the electromagnetism and the psychic energy influence psychological and behavioural functions,” she says.

These specific sonic explorations of how technology affects the human experience continued throughout the 1980s and let to the trio of recordings that she is perhaps best known for – 1983’s ‘Nortoncomputerforpeace’, 1984’s ‘Personal Computer’ and 1985’s ‘Artificial Intelligence’.

“I think that the musical content shouldn’t be an illustrative pantomime,” she says. “In my solo albums most of the tracks are instrumental: if there aren’t lyrics, everyone has a different experience of listening and of emotive understanding. The album titles are purely indicative: ‘Nortoncomputerforpeace’ is a call for non-violence and it was inspired by the human suffering, at that time, in various countries: wars, violence, hunger…”

These themes continued into the next decade with 1990’s ‘The Double Side Of The Science’, which, Norton explains, is “an observation about the ambiguous interpretations regarding the potential that science and technology can offer to humans.

“We have to enjoy the benefits,” she says, “but have we to accept the risks too. In my mind, to destroy the human habitat and, at the same time, to try to find a way of escape to other planets is madness.”

For these pieces to be so simultaneously high-minded and, well, catchy as hell, is impressive. It’s something that very few of her contemporaries would even contemplate.

As the 1990s continued, Norton’s technological savvy was matched only by her ability to work in new sounds and movements, which resulted in more primal three-part ‘Techno Shock’ series released in 1992-93.

“The music being listened to at the emerging techno rave events, especially the those in the surrounding areas of Rome, renewed my passion for the shamanic and tribal rhythms,” says Norton. “Rexanthony and I composed and recorded the tracks for the first three albums and he has continued the series up to ‘Techno Shock 10’, crossing into other genres too. It was a pleasing studio experience. Our intention? We had a lot of fun! And besides, the ‘Techno Shock’ project had a remarkable sales success.”

Alongside the academic and critical success, financial reward is not readily associated with innovators in electronic music, no matter what gender. And yet it seems electronic music is an area where women have enjoyed – especially in recent times – an equality not afforded to those working in other genres and movements. Perhaps this is due to the general absence of “rockist” sensibilities, because the sound itself is so heavily intertwined with the technology, these innovators have escaped the gender biases of other genres?

“I’ve never experienced a prejudice,” says Norton. “I’m comfortable enough in my own skin to have no problem interacting with other people… if they aren’t out of their minds. If they are, I don’t interact with them at all”.

She went on to release a series of albums that operated in the ground between techno and trance – 1993’s ‘Next Objective One’, 1994’s ‘Next Objective Two’ and 1995’s ‘Next Objective Three’.

“Maybe my brain was reorganising itself after the ‘Techno Shock’ pieces,” she speculates, “maybe my brain wanted to shut down its left hemisphere to improve the right one; maybe I was in a state of mental concentration, in a mystic absorption… I don’t know why I did them, I simply did them.”

Get the print magazine bundled with limited edition, exclusive vinyl releases

Regardless of why she created them, they made a massive impact in the clubs. How does she feel about the recent developments in music consumption and production which have, arguably, followed in the wake of her own sense of progressiveness?

“The modern digital jukeboxes contain overloaded libraries, millions of songs available to stream, an ever-expanding database,” she says. “Electronic music equipment has come a long way and is now is available at an affordable price, which enables everyone to be ‘producers’. And everyone includes not just the artists, but also emulators who are unable to create something original. Millions of songs, millions of producers, millions of seconds to choose some interesting tracks. To discover new music within our preferred genres is getting harder and harder… and more frustrating.”

Paving the way for computer-based composition while retaining an accessible and commercially successful sound, for those who are not yet familiar with Norton’s work, the recent vinyl reissues on on Alessandro Adriani’s Mannequin imprint will provide an excellent starting point.

“My life never maintains the proper rhythm of space and time,” concludes Norton, “but thanks to the reissues I’ve realised how much time has passed since the original releases.”

And they still sound like they could have been made yesterday. Or tomorrow.

Reissues of ‘Nortoncomputerforpeace’ (1983), ‘Personal Computer’ (1984) and ‘Artificial Intellingence’ (1985) are out on Mannequin