Arab Strap’s Aiden Moffat retires his L Pierre side project with a fourth album, a vinyl-only release with no sleeve that samples a 1948 Mendelssohn concerto…

“It’s an inherently nostalgic feeling, vinyl. There is zero reason for vinyl in the modern world, there’s no reason to have it at all,” says Aidan Moffat, ironically talking about his vinyl-only, final album as L Pierre. “We make music on computers, most people listen to music on the move. The only time I really get to listen to music in depth is when I’m travelling.”

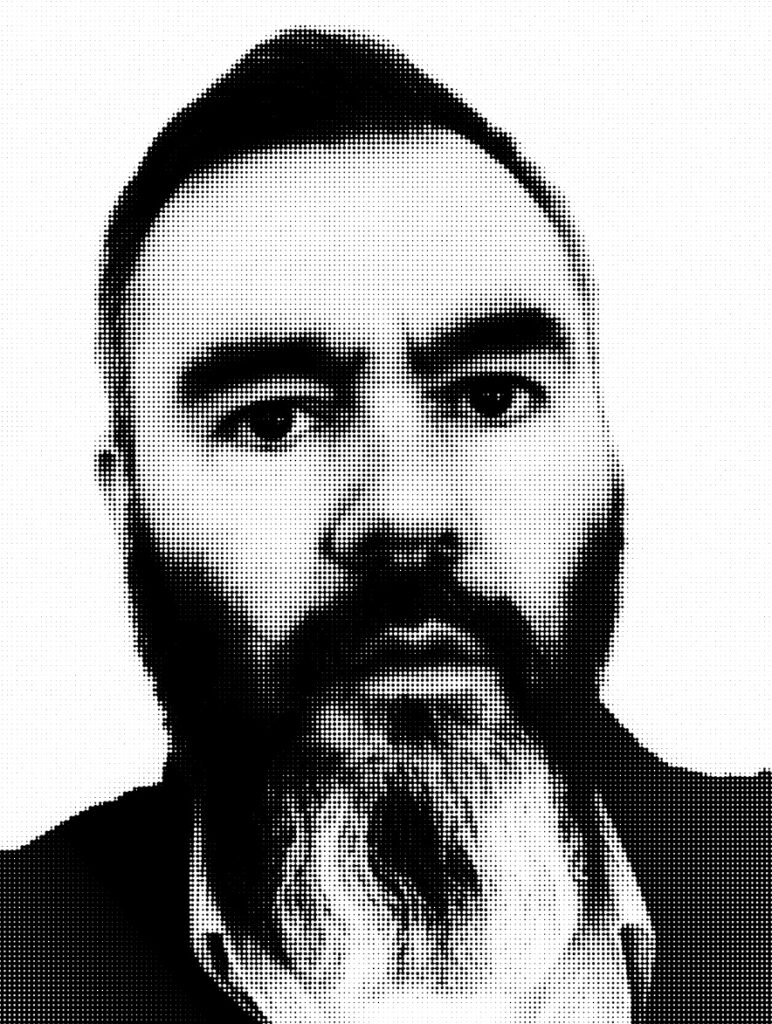

Speaking to Aidan is hugely refreshing. He’s articulate, candid (brutally honest, in fact) and speaks with a clarity on subjects he’s obviously given a great deal of thought to. Falkirk’s finest is best known for his work with Malcolm Middleton as Arab Strap, an indie outfit notorious for explicit, confessional lyrics and a characteristic mix of lo-fi guitars and synthetic beats. His L Pierre side project is quite different. It’s an instrumental, sample-based undertaking where loops and moods are lifted from crackly, forgotten charity shop records and made into mind-swimming musical narratives, resulting in something bittersweet and affecting. Since 2002, he’s released four albums as L Pierre. The latest, ‘1948 –’, represents a conclusion to the venture and is a post-modern exploration of the role of vinyl records in the era of streaming and instant gratification.

‘1948 –’ is created entirely from classical samples of the first-ever 33 1⁄3 12-inch vinyl album, a New York Philharmonic and Nathan Milstein version of Felix Mendelssohn’s ‘Concerto In E Minor’. In places, it’s a haunting expression of elegant, sad strings, disconsolate layers emerging from the gloom; in others, the sound is reduced to an ambient smear that drifts in the backdrop. While the music itself is beautiful, ‘1948 –’ serves a purpose beyond the aural.

“There had to be a reason to do another record,” Aidan says. “It’s a lot more than just music going on with this one, it’s about how it’s released, it’s about how people are going to respond to the physical item too. I felt I had another purpose beyond just making an album, and this seemed like a good way to end the project. Because it is focused on vinyl, which is the root of pretty much all of the music that I’ve made, it seemed like the natural point to stop.”

The album is unusual not just in the way it samples from only one source, but in the manner in which it’s being released: a limited run of “naked” vinyl records with no sleeve.

“That surface noise, the grit of the samples, has always been a part of the sound I’ve used,” he explains. “I wanted to take that a step further and make each record unique. When I was younger, you could identify your copy of an LP because you knew where the scratches were, you knew where the pops were. I wanted that to be part of the sound of ‘1948 –’ too, for that surface noise to be different on each one. But then there was also the idea that I don’t want the music to be this pristine thing that can last for ever like digital music does. I wanted it to be destroyed and decayed in some way.”

Aidan was attracted by the prospect of releasing something similar to the secondhand records he’s pilfered from and in some way reanimated in the past. Ephemera that is fragile, vulnerable, and somehow poignant.

“It occurred to me the easiest thing would be to have it out in the world, naked. Exposed to the elements and see how it gets by. The idea it’s allowed to live and breathe and be damaged, as people are, gives it humanity.

That’s what attracts me to that surface noise and those samples. The surface noise of a record makes it sound like it has lived and survived. There’s a sadness and nobility to it. It’s also about protecting the record too. I thought it would be fun to see how people responded to that.”

Despite his ambivalence to wax, he’s particularly interested in the idea of the secondhand record, especially those whose covers have been scrawled upon with people’s names. Aidan recognises that behind each slab of plastic lies a story, that each record has “lived” in the sense of where it’s been, who has played it, what role it’s had in the lives of its owners.

“It’s like when you buy a book secondhand and it’s got a name written in it,” he reflects. “When I was young, I used to put those books back and think, ‘I’m not interested, somebody’s scribbled on it’. But as I get older, I like buying them and imagining who these people are, what they did in their lives. There’s obviously an implied history there, and that relates to what I was saying about that survivor aspect of vinyl too.”

‘1948 –’ also passes comment on the cyclical popularity of the vinyl medium itself, currently enjoying a revival that’s not slowing down, but speeding up. It’s the strangeness of how we engage with this analogue format, and its purpose in the era of Spotify, that fascinates Aidan.

“The vinyl resurgence is kind of overstated,” he says. “It’s people buying Queen LPs in Sainsbury’s. I was shocked to find LPs in a supermarket, but that’s what the vinyl market is now. It is mostly back catalogue and wholly nostalgic. This idea that young kids are bringing vinyl back isn’t totally true, because there’s always been a consistent vinyl market for new music. There always will be. What’s really happening is the nostalgia market is opening up.

“Don’t get me wrong, there’s a very healthy vinyl market and that never really went away, but the biggest selling new albums on vinyl are by the big players. The major labels have cottoned on to this idea and kids are out buying pop records on vinyl. But they’re not playing them, they don’t really have that connection with them.

It’s a very strange place to be in with the format. I still buy it occasionally. For instance, I bought the new Pissed Jeans LP, listened to the vinyl once, and the download 60 times. I don’t think it’s going to go away, but vinyl has no purpose for me other than to connect with that feeling I had of buying a record when I was young.”

A further twist to the making of ‘1948 –’ is the method by which Aidan sampled the music. Instead of directly taking sections from the Mendelssohn disc itself, he sampled from a YouTube stream of the vinyl album, taking a certain perverse pleasure from it being removed from the analogue source. In that regard, there’s no real need for the original record. But in the process of the music’s rebirth, he hopes he can perpetuate the cycle.

“I’m not going to do it, but if someone were to rip my album, and put it up on YouTube, I think I’d be quite pleased,” he says. “I don’t know if I should be saying that because we’ve still got 500 LPs to sell, but that’s the only way it will be available digitally. I’m going to destroy all the files. I’m waiting until it’s released, just to be safe, but all the digital files will then be destroyed so it’s only going to exist on the LPs that are out there.”

Another question is raised by ‘1948 –’. Whether the album format is dying. The consumption of music, at least via streaming, takes place mainly on a track-by-track or playlist basis today. Whole albums themselves are less popular.

“To me, the album is something that has to work as a whole,” notes Aidan. “Every album I’ve made is something that works as a coherent whole. There’s always a starting point. I’m doing a record just now with RM Hubbert and there’s a story I’m trying to tell within the songs. To me, an album is as good as a great film or a great book. It can take you away, and you can be completely absorbed in it. It can tell you something and it can speak to you, tell you something of value. Which isn’t to say an album of 10 pop songs is any less valid, it’s just my attitude to the album and what it is to me.

“Most pop albums were always a collection of singles and a few other shite songs to make up the space. You look at the first few Beatles albums, there’s some right stinkers on there among the genius hits. Soul records were pretty bad for that too. You buy a Four Tops album, which will have five absolute classics on it and five utter turds! Pop music was always that way. It’s kind of come back round to the idea that when the LP started it was for grown ups, it was for an adult market.”

More than simply a concept or an art statement, ‘1948 –’ should live on as a captivating album, whether it’s discovered on YouTube or in the Oxfam racks in years to come. Whether vinyl persists itself, the music deserves to.

L Pierre’s ‘1948 –’ is released by Melodic