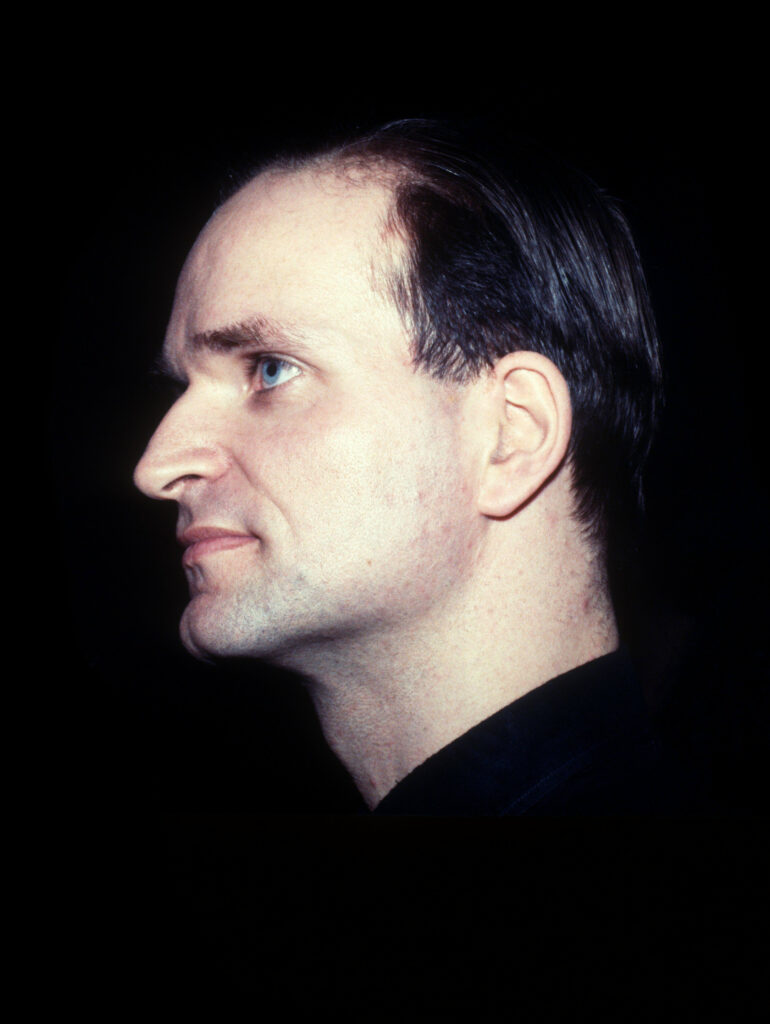

Following his death in April at the age of 73, we look at the remarkable contribution Kraftwerk co-founder Florian Schneider made to electronic music

He may have been estranged from Kraftwerk for more than a decade, but the death of Florian Schneider-Esleben at the end of April still felt like the wrenching final chapter in a glorious musical journey. Alongside Ralf Hütter, he was half of the most revolutionary duo in electronic pop – Mr Kling and Mr Klang, the Lennon and McCartney of techno-utopian futurism. The 21st century cultural landscape would be unthinkable without the innovations born from Schneider’s stringent sonic perfectionism.

On a more human level, Schneider also brought much-needed warmth, humour and comic anarchy to Kraftwerk, even in their most sternly robotic moods. The band’s most recognisable member, with his wide smile and high forehead, he counterbalanced Hütter’s starchy restraint with wry charm and mirthful mischief. In concerts, interviews and TV appearances, it was always Schneider who broke the fourth wall and subverted the serious artist pose, sometimes risking cheesy grins or silly walks as he left the stage. The subtext was clear. Kraftwerk’s deadpan minimalism was quietly hilarious and he was in on the joke.

The son of a celebrated modernist architect, Paul Schneider-Esleben, Kraftwerk’s co-founder was born into wealth and privilege, but his rebellious attitude was shaped by the radical political and cultural climate of the late 1960s.

Florian Schneider first met Ralf Hütter on an improvised music course at the Düsseldorf Conservatory in 1968. This long-haired, leather-trousered, hippy student pair listened to raucous proto-punks like MC5 and The Stooges. On Düsseldorf’s bohemian art scene, they rejected their staid classical training and experimented with free-form jazz-rock.

Neu! and Harmonia guitarist Michael Rother, who briefly played in an embryonic Kraftwerk in 1971, recalls Schneider as an angry young man.

“Florian had all these tensions in him and he was quite the opposite of a relaxed person,” Rother tells me. “We tried to record the second Kraftwerk album with Conny Plank, but there was so much fighting going on.”

Rother confirms that Schneider’s electronic experimentalism was evident even in 1971.

“Florian came from the flute,” he says. “He was a member of the classical orchestra, but at that time he was already manipulating the sound with small gadgets like equalisers and delay machines and fuzzboxes. The results sounded electronic, but it wasn’t anything near computers or synthesisers.”

As Kraftwerk’s signature mechanised sound evolved, Schneider explored the limits of primitive analogue gear like the EMS Synthi A and Votrax speech synth. Throughout the band’s formative years, he would also approach computer programmers and engineers for help in creating custom electronic instruments.

“Florian was very good in persuading,” Hütter told LA Weekly in 2005. “We have always had scientists and friends helping us out. Because especially in the early days, things were unaffordable for us. The big computers, they were with Bell Laboratories or IBM.”

In 1976, Kraftwerk commissioned a bespoke sequencer from Bonn-based synthesiser specialists Matten & Wiechers. The Synthanorma Sequenzer would prove crucial to the pristine sound of ‘Trans-Europe Express’ and ‘The Man-Machine’. Schneider later collaborated on equipment with key industry insiders including Ludwig Rehberg of EMS-Rehberg, Franz Sennheiser of Sennheiser Electronic, and Eurorack modular synth system pioneer Dieter Döpfer. In 1990, Schneider himself patented the Robovox, described as “a system for and method of synthesising singing in real time”, which was first heard on Kraftwerk’s 1991 remix collection ‘The Mix’.

“Ralf described Florian to me as ‘a sound fetishist’,” says writer and filmmaker Simon Witter, director of the 2013 documentary ‘Kraftwerk: Pop Art’. “He was clearly a huge part of their strategy of approaching people in large computer companies to design instruments that didn’t already exist to produce sounds that didn’t already exist. When Mr Sennheiser showed them an early vocoder, Florian complained that it sounded too human and asked him to make it more robotic. He was instrumental in Kraftwerk sounding so completely unlike anything else going on in the 1970s.”

Author, academic and musician Sean Albiez, who edited the 2010 essay collection ‘Kraftwerk: Music Non-Stop’, likens Schneider’s crucial role within Kraftwerk to Walter Murch, the Oscar-winning sound designer and editor best known for his innovative work with director Francis Ford Coppola.

“Both Ralf Hütter and Karl Bartos in the past described Florian as a sonic perfectionist whose role was to experiment with and shape sound,” says Albiez. “But beyond that, Florian pioneered the use of vocoders and speech synthesis, sometimes working on hi-tech inventions with technicians and engineers, as in the Robovox system, but also introducing a playful or whimsical element with business machines such as the Votrax speech synthesiser or Texas Instruments’ Speak & Spell. Perhaps it’s through these machines that Florian’s voice can be heard loudest in the band’s releases.”

During Kraftwerk’s foundational years, the power balance between Schneider and Hütter was fairly equal. “Kraftwerk is not a band,” Schneider told Rolling Stone in 1975. “It’s a concept. We call it ‘Die Mensch-Maschine’, which means ‘The Human Machine’. We are not the band. I am me. Ralf is Ralf. And Kraftwerk is a vehicle for our ideas.”

In many of their media interviews, Schneider frequently played the joker to Hütter’s straight man, making flippant comments about UFOs and astrology. On one occasion, he falsely claimed the Kling Klang studio was located in the middle of an oil refinery. He also proved disarmingly charming to famous fans, taking Iggy Pop shopping for asparagus and buying cakes for David Bowie.

One of Kraftwerk’s most high-profile champions, Bowie paid droll tribute to Schneider with the krautrock-infused track ‘V-2 Schneider’ on his epochal ‘Heroes’ album.

“I like them as people very much, Florian in particular,” Bowie said in a 1978 interview. “Very dry. When I go to Düsseldorf, they take me to cake shops and we have huge pastries.”

But Schneider’s creative role within Kraftwerk began to diminish in the late 1970s, as Hütter’s dominant vision increasingly prevailed. He had only three songwriting credits apiece on both ‘Trans-Europe Express’ and ‘The Man-Machine’. By the 1980s, he was also absent from most of the band’s interviews, allowing Hütter to become Kraftwerk’s chief mouthpiece.

In the 1990s, Schneider’s media appearances became increasingly rare, bizarre and often hilarious. During a monosyllabic encounter with a Brazilian TV reporter in 1998, a visibly uncomfortable Schneider could barely suppress his giggles. In 2001, he donned a fake moustache for an interview with comedian Ill-Young Kim on the German TV channel Viva Zwei, with Schneider speaking in Spanish as the fictionalised persona of “Don Schneider”.

Whether down to shyness, privacy or tomfoolery, Schneider was fond of hiding behind silly disguises. According to some insider gossip, he would occasionally sneak away from Kraftwerk to play one-off gigs with groups of friends, once even wearing full drag to avoid being recognised and chastised by Hütter for breaking the band’s strict ban on extra-curricular projects. While this delicious rumour is hard to confirm, Schneider certainly made a brief musical cameo wearing a wig in the 2001 German TV film ‘Klassentreffen’, playing an acoustic double bass in a jazzy covers band alongside fellow electronic composer Klaus Schulze. Kuriouser and kuriouser.

For all of Schneider’s groundbreaking importance as Kraftwerk’s chief sound scientist, his stubborn aversion to touring arguably held the band back. As early as 1978, his reluctance to play live reportedly kept the group holed up in Düsseldorf, dampening the commercial prospects of ‘The Man-Machine’. Hütter cited ongoing tension over touring as a key factor when Schneider finally left Kraftwerk in 2008.

“We haven’t seen him for a long time,” Hütter told me when I interviewed him in 2009. “He just disappeared, for personal reasons. I cannot speak for my former partner, friend and co-composer, but he always hated touring and concerts. We have worked together for so many years, but he has other projects. I’m a free artist so I can continue.”

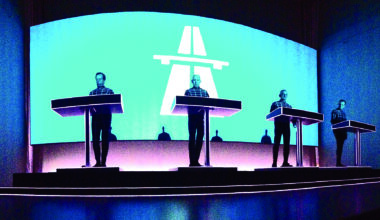

Four decades after they first conceived Kraftwerk in the heady creative milieu of late 1960s Düsseldorf, the pair had finally separated. In fairness, Schneider’s departure seemed to galvanise Hütter for a glorious autumnal resurgence. In 2009, Kraftwerk released their long-brewing boxset ‘The Catalogue’. Since then, they have performed over 300 shows, more than during the entire previous 30 years with Schneider.

Sean Albiez suggests Kraftwerk have benefited from a kind of “negative entropy” since Schneider departed, becoming far more productive and active. But something has been sacrificed too.

“After Florian left the band, I’d argue that they lost something in the live context due to his enigmatic and charismatic presence no longer balancing the four-console layout,” says Albiez. “I agree that they have been liberated, as they have become more public-facing over time, but perhaps Ralf has built a too perfect musical system that no longer allows for new inputs.”

Simon Witter concurs that losing Schneider had a mixed effect on his former band.

“As a conceptualist, Florian always believed Kraftwerk was an idea, not a band, so he would have been the first to say that his departure didn’t diminish Kraftwerk,” argues Witter. “By this logic, it shouldn’t matter at all who is in the band these days. But in the real world, I think this ideology clashes with old-fashioned notions of authenticity and uniqueness in art. Kraftwerk are fine without Florian, because Ralf provides a sense of continuity from that first revolutionary impulse at the Düsseldorf Conservatory back in 1968. Fans might well have a problem if he too were to leave.”

After quitting Kraftwerk, Schneider arguably fell victim to his own sonic perfectionism. His only new publicly released music was the 2015 track ‘Stop Plastic Pollution’, a collaboration with Dan Lacksman and Uwe Schmidt. Made for the environmental campaign Parley For The Oceans, the song was based on samples of water drops recorded in Lacksman’s Brussels bathroom. “Sorry, but the effort for recording a real ocean wave would have blown our budget, so we generated a synthetic wave,” Schneider quipped to Dazed magazine.

Asked in the same interview about the futuristic legacy of his former band, Schneider gave a pointedly dry response. “Kraftwerk has become historic and is now exposed in museums,” he said.

Florian Schneider died as he had lived most of his life, enigmatic and elusive, shielded from media intrusion. Although he passed away from cancer on 21 April, his death was only confirmed on 6 May. Billboard magazine broke the news with an unusually emotional statement from the Kling Klang HQ: “Hütter has sent us the very sad news that his friend and companion over many decades Florian Schneider has passed away.”

On social media, Schneider’s sister Claudia confirmed that Ralf and Florian had made peace again at the end. Two estranged sonic revolutionaries, Mr Kling and Mr Klang, finally back in harmony. Their Kraftwerk konzept still visionary, their musical legacy unassailable. Humans may die, but The Man-Machine goes on forever.