From Mellotrons to Claviolines, Dutch sonic project The Analogues scour the planet for vintage kit to enable them to replicate The Beatles’ post-touring albums perfectly. The band’s musical director Bart Van Poppel tells us how they’re getting better all the time

In a nondescript modern industrial estate in Haarlem, a 20-minute drive west of Amsterdam, there is a sonic laboratory dedicated to one outcome: the accurate replication in a live context of the albums The Beatles made after they stopped touring. The emphasis here is on the word “accurate”. Nothing will stop these obsessives in their quest for Beatle fidelity.

The Analogues – the above-mentioned obsessives – are on a mission, which has taken them all over mainland Europe. They can sell out large arena venues in Germany and the Netherlands with their astoundingly faithful renditions of classic Beatles albums. They now have their eyes on the UK, the Beatle motherland.

Their performances are more like live reconstructions of the original multi-track tapes, each bounced down part assigned to a live player. To that end, The Analogues leave no stone unturned. From the period-accurate gear to the orchestral parts, every note has been analysed, every shifting tempo attended to, every mistake lovingly recreated. They’ve even replicated the locked groove run out on side two of ‘Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band’, and tackled the nine-minute musique concrète masterpiece ‘Revolution 9’. More on that later…

“It started out as a joke!” laughs Bart Van Poppel, the band’s bass player and musical director.

Van Poppel is a well-known musician and producer in the Netherlands thanks to his late 80s band Tambourine and his involvement with the Prince-approved outift Loïs Lane. But the idea for The Analogues came from Fred Gehring, who plays drums in the band. Gehring played in his teens in the 1970s, but he gave it all up for his day job. The day job, mind, included becoming the CEO of Tommy Hilfiger, and then Vice Chairman of PVH Corp, an American clothing company with annual revenue of $8 billion. Which might explain how this operation is so well-funded.

“Fred and I had a mutual friend and we would bump into each other at parties over the last 15 years,” says Van Poppel. “And 10 years ago, he told me he wanted to do this Beatles project. I thought, ‘Come on, not a Beatles tribute band?’, but he explained what he wanted to do, and got me interested.”

It was another four years before Gehring had the time available to make The Analogues happen. It started with an early research trip to America to see the celebrated Beatles tribute band The Fab Four perform.

“The first thing I saw, “ says Van Poppel, “was two big boxes on the stage, full of equipment, electronic shit, samplers and I don’t know what. I told Fred that this was not what I wanted to do, I wanted everything to be visible for the audience, and everything should be real.”

No samplers, then. No boxes of contemporary computer trickery. And so the international shopping spree for vintage kit began.

“I had a lot of vintage stuff already, but we needed Beatles stuff,” says Van Poppel. “So I had to look all over the world, eBay and other auction sites to find all these exotic organs, guitars and amps.”

They sourced a Mellotron, with a serial number consecutive to Paul McCartney’s, apparently – you can’t get much more period accurate than that. One of the more obscure pieces in The Analogues’ collection is the Clavioline Auditorium. The Beatles used one of these peculiar proto-synthesisers just once, on ‘Baby, You’re A Rich Man’. They stumbled on the instrument at Olympic Studios, where it was already a relic of a bygone era, briefly fashionable in the wake of its use on ‘Telstar’ by The Tornados in 1962. Lennon played it, the story goes, by rolling an orange up and down its keyboard.

“We have two of them,” chuckles Van Poppel. Of course they do. They pretty much have two of everything, with one for the rehearsal facility, and the other kept in climate controlled trucks for touring, along with the doubles of everything else (“except the guitars,” clarifies Van Poppel).

“Everyone wants Claviolines,” says Van Poppel. “There’s a waiting list. I found a guy in the UK who sold us these. He was very nice. Most of the people who have this old stuff really like our project when I tell them about it. I always send a link from YouTube. He put me at the front of the queue because he liked what we were doing.”

Other remarkable instruments in The Analogues’ armoury include the Baldwin electric harpsichord.

“We bought this just for ‘Because’ [from ‘Abbey Road’],” says Van Poppel. “It was in Abbey Road, in the studio, and they just used it.”

Nearby is a Hohner Pianet, another quirky instrument from the 1960s, often dubbed “the poor man’s Wurlitzer”. It was the keyboard Lennon used on ‘I Am The Walrus’. Van Poppel then shows me the Lowrey DSO Heritage Organ, and plays the opening lines of ‘Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds’.

“They also used one of these on ‘Being For The Benefit Of Mr Kite!’, and a few other tracks,” he says. “Billy Preston used it on ‘Let It Be’. They’re really hard to find, they didn’t sell too many here in Holland. The problem with them is it’s hard to find people to fix them. Nobody wants to work on them. If you open it, there are about 75 tubes in there.”

Eventually Van Poppel found someone willing to service it. It spent six months in the workshop, where the engineer removed two mouse nests.

“The mice ate all the leads. It was a complete mess,” laughs Van Poppel.

When Van Poppel plays little excerpts of Beatles tunes on these elderly instruments to demonstrate them, the effect is startling. It’s not that they sound similar to the originals, they sound exactly the same, because these are the very instruments that were laying around when The Beatles made their albums. Every nuance and detail of these sounds, from the timbre to the amplitude envelope and all points between, are locked inside these obsolete and temperamental technologies.

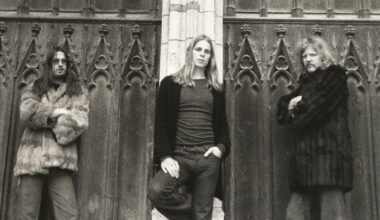

As their kit collection grew, the band was fleshed out with seasoned professionals from the Netherlands. They recruited guitarist Jac Bico, who had also been in Tambourine, keyboard player/guitarist Diederik Nomden, another alumnus of various well-known bands and, at 44, the youngest member of the band, and Jan Van Der Meij, guitarist and singer with the Dutch band Powerplay, described as a “loud McCartney” by The Analogues. Hearing issues recently put Van Der Meij out of action, and Felix Maginn of Moke has stepped into his shoes for the time being. They can all sing, which is handy when you’re trying to emulate The Beatles.

The first Beatles album The Analogues tackled was ‘Magical Mystery Tour’, so they needed a piccolo trumpet player for ‘Penny Lane’ as well as strings and horns for ‘I Am The Walrus’ and ‘All You Need Is Love’.

“We started with two violins, two horns, then another violin came along, a cello and so on… that’s where it went wrong!” chuckles Van Poppel. “It was my idea to start with the ‘Magical Mystery Tour’ LP. It’s impressive, the EP plus all those hits, it was a nice start. There’s a lot of orchestration, but it wasn’t too difficult.”

Next, though, came The Big One, ‘Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band’, probably the best-loved Beatles album, and arguably the best pop album ever made. A harp player was found for ‘A Day In The Life’, but there was more trouble ahead in the shape of ‘Within You Without You’.

Guitarist Jac Bico set about re-learning the sitar. You can hear Bico’s sitar skills on the track ‘Summer Of Love’ on Tambourine’s debut album ‘Flowers In September’. Van Poppel tackled the swarmandal, a small, stringed harp-like instrument, rather like a zither, that plays a swirling cloud of notes on the opening, and one of the orchestra’s violin players had studied the dilruba, “that’s the terrible instrument with a bow…” says Van Poppel, ruefully. When the violinist first tried to play it, he says, “it sounded horrible, I had to tell him to stop, I was getting a headache from it!”. But the player took his dilruba on holiday with him, and by the time he came back, he had perfected the part.

For 2018, The Analogues dissected ‘The Beatles’, aka ’The White Album’, which has 30 tracks over four sides of vinyl, and is the most eclectic collection of songs the Fabs put together. In ‘Revolution 9’, it boasts perhaps the most challenging Beatles composition of all to reproduce.

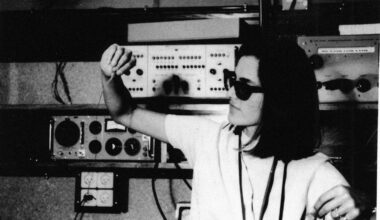

“You can’t play it,” says Van Poppel. “The first idea was that we would have five guys, each with one tape recorder, and play loops live, with one big recorder with the main soundscape, and we would be like operators in white lab coats.”

A handful of 1960s tape machines were located and purchased, but before they could try that approach, someone suggested they make a film for the piece. They approached Jaap Drupsteen, one of the Netherlands’ most celebrated graphic designers, an innovator in synchronised live music visuals and responsible for the designs of Dutch bank notes and passports.

Van Poppel was running late with his ‘Revolution 9’ rebuild, which had been put on a back burner due to the more pressing issue of guitarist and singer Jan Van Der Meij developing the hearing problems which put him out of action. And so Drupsteen went ahead and made the film using the original version.

“He designed the film with a lot of sync points based on The Beatles’ original, so I had no choice but to do a complete remake of it,” says Van Poppel. “I recorded everything, all the fragments, all the parts. It was a hell of a job, but the film Jaap made was incredible. Suddenly the whole soundcape from Lennon came to life, he made everything visible.”

Van Poppel’s reconstruction of ‘Revolution 9’ was a two-month labour of love. He took all the parts that were created by running tape backwards, isolated them, reversed them, and then copied what was revealed, playing the parts himself, and then reversed those, before placing them in his new version of the collage.

“I had to find a good voice for the ‘Number nine… number nine…’. I got my wife to do the ‘When you become naked…’ part. We re-voiced it all. There’s a lot of text you can find on the internet, but some of it is bullshit, sometimes we just changed it, we did our own text. It’s amazing when you hear it; it’s different, because I made all the parts, but you immediately recognise it as ‘Revolution 9’.”

It could well be the first-ever cover version of a piece of musique concrète. After all, who else would do something so mad?

Their show at the London Palladium in May was a time-warping triumph, with the biggest cheer of the night going to Bico and his faultless solo on ‘While My Guitar Gently Weeps’. But the sheer bravado of the ‘Revolution 9’ remake garnered a reaction of stunned disbelief from the audience.

Next up for The Analogues is ’Abbey Road’, which, together with ‘Let It Be’, is going to make up the next phase of The Analogues repertoire. They’ve just performed ‘Abbey Road’ in full with a small invited audience at – where else? – Abbey Road studios. It was being recorded for an album release, which will join their versions of ‘Magical Mystery Tour’, ‘Sgt Pepper’ and ‘The White Album’ in their strange back catalogue.

The Analogues express something important about pop culture, that the music of The Beatles is part of the canon of 20th century music. It has transcended tribute band territory, and now is starting to occupy a new kind of space, more like the context in which we understand classical music, but where the appreciation of the music extends to the process of its recording.

So finally, what has Van Poppel learned from this intensive analysis and reproduction of the work of the greatest band of all time?

“How sloppy The Beatles were, and that they kept their mistakes,” says Van Poppel. “These days, we are too scared of making mistakes.”

Analogue by name and by nature, The Analogues are pursuing the perfection of imperfection, ensuring an analogue for the future of our precious analogue past.

For more, visit theanalogues.net