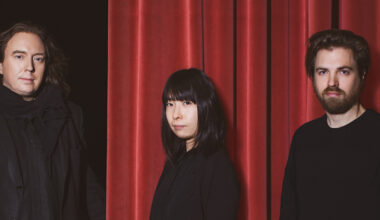

When two of the world’s finest contemporary composers get together for a chat, best leave them to it. Here Volker Bertlemann, aka piano preparer extraordinarie Hauschka, rolls out the questions for Max Richter

Hauschka: Since we met the first time in Düsseldorf in 2005, what do you think has changed in your approach to composition?

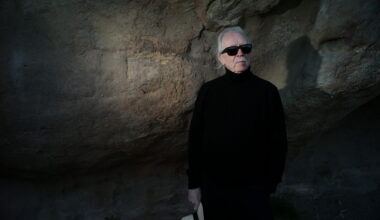

Max Richter: I don’t think my approach has really changed. It’s more a question of continuing to move outwards into an unknown territory. The landscape is out there somewhere, and the writing is a way to make it known. I feel like this hybrid language I’ve been evolving over the years has plenty of miles left in it yet!

H: How do you approach a composition like your new ‘Woolf Works’ album?

M: ‘Woolf Works’ is a laboratory, we put all the elements into the same space and watch how they start to speak to one another. So music history meets the text, dance meets narrative, electronic sound meets the physicality of the dancers… It blows up in all sorts of directions and part of my job is to try to keep up with the new ideas that the material itself throws up. When the thing starts to feel like its alive, that’s the exciting part.

H: How does a collaboration with a choreographer differ from, say, a film project?

M: Every project is different and has its own world. Part of what we are doing is trying to discover what the rules of that world are, either creatively or in terms of its process, and cinema is no exception, so it really depends on the people an circumstances around the film. I’ve been lucky to work with some very creative folk who value music. Writing for dance always starts with a completely blank slate, for ‘Infra’, my entire brief was, “It’s 25 minutes long”.

H: Is the number of pieces you write accidental or do you have a clear outline?

M: I’m basically always writing, the amount of released music is only a part of the material I make. In a way its an involuntary process, but one I’m happy to be a part of. Music is a beautiful thing to spend your time doing.

H: Since you work with a major classical label , how has that changed the reach into the indie world and is that something that is for you important?

M: I can’t tell if there has been any effect, I just keep on keepin’ on. I’ve never really thought about this classical/indie polarisation. I don’t believe the audience listen in terms of categories in any case. I think people like hearing music they enjoy, wherever it comes from. It is the same for artists – we follow the things we love. The reason I went to FatCat in 2003 instead of a classical label is because they were releasing work I loved.

H: Have you ever felt as a part of the so-called neo-classical movement?

M: I don’t really like this use of neo-classical, in my brain it refers to music from the 1920s and 30s, kind of mid-period Stravinsky. As a joke I made up “post-classical”, as a way to answer the question “What’s your stuff like?”. At the time, there was no scene of any sort to relate it to, and therefore it always took a really long time for me to answer that question. I’m not really a “movement” person – these things are mostly made up by marketing departments in any case and I’m more interested in the sounds and music I’m involved with.

H: How do you keep your creative approach fresh? Do you try and create new things or is it more a case of staying with the things that are strong and working?

M: Well, I always think I’m heading off in new directions, and I really like that idea, but when I look back it always sounds like me. When I start writing, it’s more a case of which one of the things buzzing around in my head to write down. Usually an idea for a project and some material will just suddenly stick together.

H: How long does a composition like ‘Woolf Works’ take you?

M: On and off I worked on it for a couple of years. But the ballet and the record are quite different. The ballet is over two hours, so it was a fairly lengthy process of refining and reshaping to get to the point of the record.

H: I know you have a strong connection to strings and piano, have you ever thought about changing instrumentation completely?

M: I love the piano, it’s always been my sketch pad and I love the immediacy of it and the sound it makes. Basically I love everything about it. My studio is out in the country, in the middle of nowhere, and guess what, the piano even works when the power is down! I love the orchestra too, 500 years of R&D, it’s the perfect synth! I use it rather minimalistically in terms of colours, so that my orchestral music doesn’t feel “orchestrated”. You won’t find lots of colour shifts in the language. It’s a personal preference to keep things as simple as possible I guess.

H: Do you think to make powerful art you have to somehow suffer? And do you think that success takes away the need of getting deeper into the expression of things?

M: I don’t know. I’d made ‘Memoryhouse’, ‘The Blue Notebooks’, ‘Waltz With Bashir’, ‘Songs From Before’, ‘24 Postcards…’ and ‘Infra’ before I started to be able to feed the kids in a stable way, sorry kids! It was a hard journey and I think it made the writing process, as well as the living process, much more difficult. Though of course, I’ve only lived one life, so I don’t have a comparison. More generally I think everyone has something unique to say and if music is your language then you should focus on the music rather than anything else, and certainly not “success”, because that is a very, very elusive thing.

H: In Düsseldorf , where I live and which has a strong and intense art history, being successful and yet not getting into mainstream areas has a high value… what do you think about that as we both are travelling between these worlds?

M: I don’t think it is either/or. After all there are some very prominent artists who do great work, Radiohead, Björk, John Adams… as well as lots of folks sitting in bedrooms writing terrible music. So I don’t think the mainstream rules out good work or the indie scene guarantees it. It depends on the artist, and their sense of commitment to the work itself rather than anything surrounding it.

H: Who is your favorite classical composer and what kind of electronic music would you consider as your biggest influence?

M: Bach is my favourite, he is more than just a composer, but rather an inventor of the language we all use. Among “normal” composers I love Schubert. In the electronic sphere I have to say Kraftwerk, they lit my brain up when I was a kid and I’ve never gotten over it.

That was good wasn’t it? But what if the tables were turned and Max Richter becomes the interviewer putting the questions Hauschka? One step ahead of you there…

Max Richter: What was your favourite song when you were 12?

Hauschka: Oh, Queen’s ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’…

MR: That’s got a great piano part, I learnt it from the record as a kid. Do you remember when you first started to play the piano?

H: At the church where my parents were very active, I saw a concert by a man who played Chopin, I was about nine. I don’t know which piece, but I was deeply touched. After the concert I told my mum that I wanted to have piano lessons with the man we’d just seen teaching me. I still remember the earthquake that was happening inside of me.

MR: When did you discover there was more to the piano than just playing on keys?

H: I was 12 I think. I was quite interested in synthesisers and when I played the piano it felt so minimal, very few sound options, so I treated every hammer of my piano to make it sound like a cembalo [harpsichord]. So that was my first experiment with the instrument and then when I was older I used the idea to express my love for modern electronic music without using a laptop.

MR: Do you feel connected to other artists who’ve explored this expanded aspect of the piano?

H: I feel very much connected to John Cage and especially his music theory. Nancarrow was always fascinating for me as he stands for a beautiful analogue metamorphosis of instrument and machine.

MR: It’s interesting you mention the idea of trying to get to the aesthetics of electronic music by acoustic means, your new ‘What If’ album feels like this is happening in an amazing way. Is that still your aim?

H: Oh yes it is. Electronic music works for me in an interesting way. Just the association is enough to get rid of my attachments or restrictions.

MR: When you set out to make the new record, did you have a clear plan in mind?

H: With my previous albums I’ve only worked with upright pianos, so I wanted to work on a big grand piano. The compositions are all based on improvisations or on pre-recorded sequences. The only clear plan I has in mind was to work with Disklaviers [state-of-the-art Yamaha pianos] and to record my music in a different studio then my own.

MR: With this record you seem to be taking your harmonic language a lot further into a more abstract space. Was that deliberate?

H: I wanted to go in a more extreme direction, because I felt my solo records, in a way, have the space to go into the extremes without restriction. I am the only limit.

MR: Do you ever listen to your own records? If so, do you see things in your old music that you were not aware of putting there at the time?

H: I do listen to my old records every now and then and I am sometimes quite surprised about what I did in the past. Listening back to [2008’s] ‘Ferndorf’, my ability to record strings has developed… I didn’t have the best microphones at that time.

M: To what extent is making new music research for you?

H: It’s definitely research, making music for me is not just to fulfill the next obligation or to do the next job. Making music is always a very playful and joyful process. It’s sometimes a question of how radical the approach is… sometimes I want a risky way of making a new record and listening back I find out that I went back into safe waters and didn’t allow myself to be more leftfield, which is weird, and then I try to create obstacles to make me work harder to get into a new space.

M: Obstacles are very useful enablers! I wonder if you have a favourite piano?

H: Because every piano has its own sound and its own strengths, I don’t have a favorite. The Steinway grand is always solid, but for some purposes the Yamaha grand pianos are better… especially when you amplify them. I also love the Bösendorfer grands for their extreme balanced sound.

M: Do you ever play, say, Mozart for fun? How do you see the relationship between your work and music that has gone before?

H: I love to play other composers for fun, but I am not a good sight reader so it takes me a while to learn a piece, but once I can play it I am amazed. I think my music is inspired as a result of all the music I was in touch with and what I am listening to now. Sometimes I hear specific classical composers and hear similarities to my approach so I try to understand what that is and where it comes from and that gives me and my work a lot of input.

M: What do you make of the various descriptions around current instrumental music? Do you recognise terms such as “neo-classical”?

H: I recognise these terms and think they’re sometimes necessary, but they don’t cover the spectrum. I am definitely not feeling neo-classical even though I am pushed into that box. Suddenly you are in a box with all sorts of composers or musicians that you don’t feel similar to. The selection of who belongs to which group is just down to having a phenomenon of people like us that are all working with a piano in an electronic background at the same time… often hearing their music makes you think you are not a part of that group.

M: Do you have a sense your records are part of a larger narrative?

H: I think they are connected with each other and they build onto each other, even if the sound is pretty different. I am driven by the desire to find new sounds and learn how to transport these sounds into ensembles or other instrument or into films or even ballets. I think you can see there has been a development, mainly in the involvement of electronic music.

M: In recent years it seems like you have broadened your pallette to include more orchestrated material, what’s driven this?

H: I think it’s helpful to move away from your instrument and try to find an expression outside of you as a performer. For me it was pushing myself into writing. I like the fact that I’m forced to express myself outside my comfort zone.

M: You are now Oscar-nominated for your collaborative score with [composer and A Winged Victory For The Sullen’s] Dustin O’Halloran for ‘Lion’, congratulations! Can you talk about how writing for film differs from writing “pure” music?

H: As you know, when working for film there are many people involved who make decisions, so to actually work as you want happens very rarely. With ‘Lion’, myself and Dustin had the freedom to make the music that came in our mind. The collaboration process was a wonderful experience, it only works when you are able to step back and let things unfold. With Dustin that was possible and we created a workflow that allowed us to send an idea in the morning and the other person was taking it and stripping it down or adding things… or even sometimes nothing was left from the idea, but it transformed to something new. We had the space to create our own vision and that is very strongly reflected in the score.

M: Now that your projects have more visibility, with a larger audience, do you feel differently about the creative process?

H: Not at all! I think the creative process should be detached from the visibility. The only thing that has changed are the options and that you have more opportunities to create bigger projects, but that is pretty dangerous as the bigger projects are, a lot of times, not the best projects because they need time and preparation and as we know that is increasingly rare.

M: It is! Last question… what is your perfect breakfast ?

H: Fresh, dark crusty bread with butter and marmalade , a soft boiled egg or three scrambled eggs and an espresso macchiato

M: Wow! we are breakfast twins…

H: I am not surprised.

Hauschka’s ‘What If’ is released by City Slang