She was the founding director of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop and the inventor of Oramics, but there are big gaps in what we know about Daphne Oram. Join us on a road trip with a difference to discover more about the first lady of British electronic music

I’m standing on the pavement of Delaware Road, London W9, in search of Daphne Oram. I’ve talked to several Oram experts and to someone who actually became Oram for a while, more about her later. I’ve visited the Daphne Oram Collection at Goldsmiths College, University of London, and sifted through her handwritten notes, correspondence and photographs, trying to learn about the life of this remarkable woman and get a handle on Oramics, the radical electronic sound invention that remained her life’s unfulfilled work.

And now I find myself on some kind of peculiar psychogeographical drift through the south-east of England, from London to Kent, from Maida Vale Studios, where Oram set up the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, to her home studio in a converted oast house. I’ve convinced myself that treading some of the same ground as her will give me an insight into one of the UK’s most important but overlooked musical innovators. Perhaps if I follow the imaginary ley lines of her working life, I will reach a deeper understanding.

Daphne Oram believed that the resonances of the natural world held the key to a more profound connection to life itself, as evidenced by her interest in the esoteric research into the sonic properties of ancient architecture, so I like to think she would approve of my Oram-focused wanderings. She did, after all, attend seances organised by her father in the 1940s, where on one occasion the medium channelled a spirit who announced that Daphne (then aged just 16) was destined for great musical achievement. On the other hand, her fierce intellect and no-nonsense demeanour may well have seen me chased out of town on the wrong end of a hot soldering iron.

But back to Delaware Road. One side of the street is occupied by Delaware Mansions, rather grand five-storey housing blocks built in 1905 and filled with well-appointed, high-ceilinged apartments. Opposite these is an enormous, low profile, white-painted structure. The roof is seemingly made of corrugated iron, giving it the jarring appearance of a vast shed lurking behind a fancy stucco frontage.

The purpose of this odd construction is further disguised by its double-height arched entrance, which is lavishly adorned with flowing carvings of hanging vegetation, gargoyles and ribbons, in a style known as Edwardian Baroque. Revered Radiophonic Workshop alumnus Brian Hodgson, the man responsible for the sound of the TARDIS and the voice of the Daleks on ‘Doctor Who’, once described the building as looking like “a decomposing wedding cake”, and you can see what he was getting at.

This is the BBC’s Maida Vale Studios, home to MV1, one of the largest broadcast spaces in Europe, which was designed to house the BBC Symphony Orchestra. There’s a warren of other studios tucked away in the building too. The Beatles recorded dozens of songs for BBC broadcasts between 1962 and 1965 in one of them. Hundreds of bands, from Bogshed to Radiohead, traipsed in and out of here to record sessions for John Peel’s show over the decades.

It seems unlikely, but this place was meant to attract crowds of roller skating enthusiasts when it was built in 1909 and 1910 by one Louis Napoleon Schoenfeld, an American entrepreneur who thought London needed a 2,900-capacity skating rink with a gallery that could accommodate an entire orchestra. The residents of Delaware Mansions must have been less than delighted to see such a vulgar attraction open up on their doorstep and relieved when it closed in 1912, its visionary skating enthusiast owner having been declared bankrupt.

Twenty years later, the British Broadcasting Corporation bought the building and converted it into a studio complex. And it was here that Daphne Oram arrived in 1958 to start her new job as the first director of the Radiophonic Workshop, the future-gazing experimental music facility she had been badgering the BBC management to fund for years. Oram was full of enthusiasm and ideas for a studio that would produce a different kind of music, created electronically and with tape, that she believed would shift and expand the listening public’s perception of sound itself.

A scrap of paper in her archives at Goldsmiths reveals some of her thinking about what the Radiophonic Workshop might address:

“We do not place a microphone in front of a West End theatre stage and say, ‘Here is a play’. We take the cast into the studio and enhance the play using radio techniques, making it a new type of art form. With music, we are content to place the mic in front of the concert platform and say, ‘Here is a concert’. We have not developed a musical art form which is authentic radio.”

Daphne Oram had been at the BBC for 16 years by this point, having joined as a junior sound balancer in 1942 and worked her way up to becoming a studio manager. During the war, one of her many duties was working on live broadcasts of the Proms from the Royal Albert Hall. After she had completed the mic placements and sound balancing, she would tuck herself away high up under the concert hall’s famous glazed dome and hover over a turntable. In the event of a bomb forcing the orchestra to abandon their performance, Oram was told to drop the needle on a disc of the piece being played so the broadcast would continue seamlessly. In her personal notes, I find a handwritten account:

“1944 Proms was stopped because of doodlebugs. I recollect rigging Albert Hall with mics up in the balcony, thought a doodlebug landed not far away. Gosh, there was a lot of glass above me!”

It was this experience that partly informed her 1949 composition ‘Still Point’, an exceptional piece for two orchestras and electronics. She mentions it in her archives:

“In 1949, I wrote a 35-minute composition for two orchestras, five microphones and manipulated recordings, full score in 1950 completed and submitted to the music department…”

In the same box is the original score itself, Oram’s neat pencil marks filling page after page of the manuscript. The score was later misplaced for a lengthy period of time and it would be nearly seven decades before the piece was finally performed, realised by the composers James Bulley and Shiva Feshareki at the Royal Albert Hall Proms in 2018.

“When Daphne Oram died, Hugh Davies went to her oast house and sorted through all her stuff,” James Bulley tells me. “He then brought it back to his house in London. It took up the whole bottom two floors of his house for quite a number of years.”

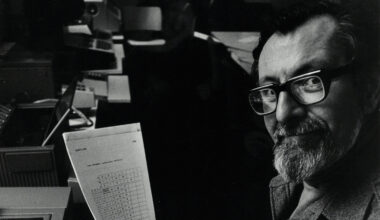

Composer, researcher, author and archivist Hugh Davies is another overlooked lynchpin of British electronic music. He spent a couple of years as Karlheinz Stockhausen’s personal assistant in Cologne in the 1960s and later published the ‘International Electronic Music Catalogue’, which sought to list every electronic piece ever recorded. It was Davies who kept the torch burning for Oram’s legacy and the score for ‘Still Point’ was eventually found among his personal effects after his own death in 2005.

“It’s a totally extraordinary piece,” continues James. “She was 23 when she wrote it, which is just… how is that possible? She had no avenue to test it. No rehearsals. It wasn’t performed. It’s full of the most incredible ideas, some of which I’ve never come across in anybody else’s work since, and that includes all the Stockhausens and Cages.

“It’s a bit like the film scores of Bernard Herrmann or Franz Waxman. It’s almost a bit much in places. There’s incredible turntablism and sampling and, on top of that, there’s live manipulation of the orchestra through five microphones using echo. At certain points in the score, it’s kind of like, ‘Now fade up the horn section a bit louder, because you’ve got a spot mic on them, and add echo’, and that’s just part of the live performance. It’s a route that would have completely changed electronic and classical music.”

If ever there was a composition ahead of its time, it’s ‘Still Point’. But Oram, who wanted the piece to be entered into the recently launched Prix Italia competition, wasn’t able to muster any enthusiasm for it within the BBC and it was shelved.

“She had so many ideas going on, I don’t think it was the be-all and end-all,” adds James. “She had just started to get reports of Cage and Maderna. She was also into Eimert and all the experimental stuff that was happening over in Europe.”

Oram’s ideas for an experimental music facility at the BBC mirrored the studios of Radiodiffusion-Télévision Française (RTF, the French public broadcasting organisation) and Westdeutscher Rundfunk (WDR, the West German broadcasting company), where composers like Pierre Schaeffer and Stockhausen enjoyed the patronage of the state and were free to explore the possibilities of electronic and tape music. Her efforts began to gain traction with her bosses in the mid-1950s, and by 1957 she was the sole member of the Radiophonic Unit, based in Room B6 at the BBC’s Portland Place building in central London.

As part of her campaign, Oram had laid out plans for multitrack recording, which was virtually unknown at the time. She often worked at night, filching tape machines from neighbouring empty studios in order to create pieces like ‘Private Dreams And Public Nightmares’, “a radiophonic poem” by Frederick Bradnum, which was broadcast in October 1957. It began with a five-minute disclaimer, voiced in a fabulously rakish BBC intellectual drawl, softening up listeners to Third Programme (later known as Radio 3) for the weird sounds they were about to encounter.

“Many of you may be familiar with it,” says the presenter in the introduction. “They’ve been exploiting it on the continent for years, but strangely enough we’ve held aloof. Partly from distrust. Is it simply a new toy? Partly through complacency. Ignorance too. We’re saying at last that we think there’s something in it. But we aren’t calling it ‘musique concrète’. In fact, we’ve decided not to use the word ‘music’ at all. Some musicians believe that it can become an art form itself. Others are sceptical. That’s not our immediate concern. We’re interested in its application to radio writing – dramatic or poetic – adding a new dimension. A form that is essentially radio.”

The work Oram produced during this period was radical and endlessly inventive. She was manically busy, with radio producers queueing up to book some radiophonic action to position their drama productions at the sharp edge of the fashionable avant-garde. Her papers include a memo to director Robin Midgley, who was very keen to have some radiophonics for his upcoming radio production of a play called ‘Candy Striped Dream’.

“Thank you for your memo, 28th November 1957,” writes Oram. “We looked into every possible way of providing staff to help create the radiophonic effects you would like, unfortunately… due to pressure of programmes we are unable to release anyone else…”

The fact that there wasn’t “anyone else” other than Oram isn’t mentioned.

The BBC finally granted Daphne Oram her wish in April 1958 and the newly named BBC Radiophonic Workshop opened for business in Room 13 at the Maida Vale complex. The writing was on the wall from the beginning, however, and I don’t mean the famous quote from Francis Bacon’s 17th century novel ‘New Atlantis’, which Oram framed and displayed, describing the “sound-houses” of an advanced civilisation where “we practise and demonstrate all sounds and their generation…”.

The shopping list of advanced studio equipment she had put together, including her plans to create a multitrack recording facility, were effectively scotched by her managers. They fobbed her off with a budget of £2,000, a motley collection of malfunctioning tat lifted from the Royal Albert Hall, and retired gear from other BBC studios. The Radiophonic Workshop rapidly became an under-resourced sonic sweatshop, with just four staff – Oram, drama producer Desmond Briscoe, and technicians Dick Mills and Richard ‘Dickie’ Bird – squeezed into a small room, with Oram undertaking most of the commissions herself.

A research trip to the Brussels World’s Fair in October 1958 must have been a welcome break for her, but it was also a stark reminder of how much more agreeable creative life was for her contemporaries on the continent. The Goldsmiths collection contains some fascinating material relating to this visit. There’s the address of the hotel Oram stayed at, a chit from the finance department outlining her £58 BBC expenses allowance for the trip, and the programme for the concerts that were on during the week she visited. It reads like the line-up for Glastonbury for the early electronic music fan – Pierre Schaeffer, Pierre Henry, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Edgard Varese, Luc Ferrari, Luigi Nono, Bruno Maderna, Luciano Berio, Henk Badings, Herbert Eimert, György Ligeti, Henri Pousseur, John Cage, Olivier Messiaen… The list goes on and on.

“Six whole days of experimental music,” she wrote shortly afterwards. “Even without its setting among the brilliant Brussels international exhibition, this prospect would have stirred the expectation of any young, modern musician. There were to be lectures by Stockhausen, Eimert, Berio, Pousseur, and others… compositions by composers from Berlin, Cologne, Italy, Holland and Belgium, and musique concrète by Pierre Schaeffer and his colleagues in France. Surely, at last this was going to be the opportunity for the new trends in music to stand on their own feet and show that the time had come for full recognition by the musical world.”

Oram’s attempts to gain recognition included sending a reel of tape of electronic music to Yehudi Menuhin and I stumble across his reply in her archives. He hasn’t had a chance to listen to it yet, he confesses.

“It will be interesting to see what guiding principles emerge from this completely uncharted world,” he says. “Electronic music allows us the control of tone colours and kinds of sounds including noises, and until these are accurately assigned relative values to each other, the perfect electronic technique can hardly emerge.”

By the end of 1958, Oram believed her vision for a state-backed resource for avant-garde composers had been reduced to what the BBC considered a special effects department. Thanks to pressure from the BBC’s in-house musicians, the Radiophonic Workshop’s output couldn’t even be called music. Oram was overworked and underfunded, struggling to create masterpieces of sound design and radical radiophonic composition with inferior equipment. The final straw came when the BBC insisted she could only work three months at a time with the electronic gear before being rotated back to her pre-Radiophonic duties, as if she were in danger of industrial injury via waveforms. This rule, it seemed, didn’t apply to Desmond Briscoe.

In January 1959, Oram decided she was not going to put up with this situation any longer. She handed in her notice and abandoned her BBC career, leaving the Radiophonic Workshop, the institution she had fought so hard to create, in the hands of others.

While we have you, why not take a minute to browse our online shop?

We’ve got print magazines, limited edition vinyl, must-have books, CD boxsets, and we ship worldwide. Click below to open a new tab and keep your current reading place.

After Daphne Oram quit the BBC, she established her own studio at Tower Folly, a converted 19th century oast house in rural Kent she’d owned since the early 1950s. For the next 20 years or so, Oramics was at the centre of her work. She shuttled between Tower Folly and London, taking on commercial work for television and radio advertising, as well as theatre and other commissions, while developing her Oramics machine.

Oramics was a groundbreaking notion for a musical composition tool. It’s probably best described by Oram herself.

“Oramics is a new way of making music,” she declared. “It is a system for converting graphic information into sound. Each parameter of the sound required is defined by drawing freehand the necessary graphs.”

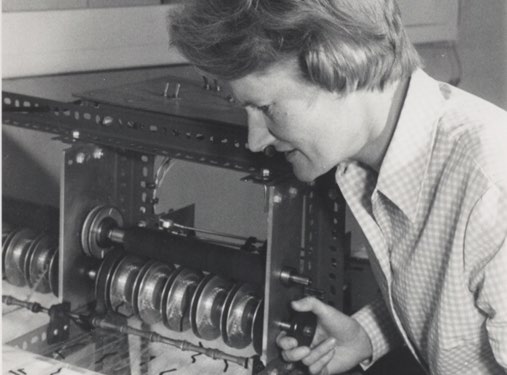

Oram had first imagined a device that she could draw onto to create any sound she liked when she was a child, and she developed the theoretical framework for it throughout the 1950s. In the 1960s, she made the prototype machine with funding from the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, assisted by her brother John (with whom she established the company Essonics Ltd) and engineer Graham Wrench.

It’s unclear what happened to the Oramics machine after Oram’s death and there’s something of a veil of discretion drawn across the circumstances of how it ended up in France, in a barn in Normandy which was apparently intended to be a synthesiser museum. But that’s where it was found in 2009, literally covered in dust and cobwebs, tracked down by Mick Grierson, co-founder of the Daphne Oram Trust. It was brought back to the UK and put into the loving care of the Science Museum, where it took pride of place at the ‘Oramics To Electronica’ exhibition in 2011.

Tower Folly is the next stop on my Oram odyssey. According to a demonstration tape Oram made as part of her efforts to drum up interest in her studio and Oramics, Tower Folly is a mere “28 miles from Piccadilly Circus”. The drive from London today takes you on the A20, then onto the M20, and within an hour I’m parked in its shadow.

It’s quite difficult to get a handle on the architecture of the place. The circular oast house looms above several other attached buildings that have obviously been added over the years. The conical roof is festooned all around with windows at different heights. It looks like something from a hallucination of a Walt Disney animator in the 1930s – part ye olde rustic farmhouse and part weird princess tower.

My immediate problem is I have no idea where the front door is. I wander around and knock at several likely and unlikely candidates, and I’m about to leave when a man appears, walking towards me from the middle of a sprawling grass plot. He doesn’t seem alarmed by my presence.

Ron Morrow and his partner Jenny Brown are the current owners of Tower Folly. Jenny is an artist and Ron has been involved in the music industry for decades. Ambient Soho, the record shop he opened in Berwick Street in London in the 1990s, spawned the electronica label Worm Interface. He’s still making a living selling vinyl. You’d imagine, therefore, that the couple were drawn to Tower Folly because of Daphne Oram, but Jenny Brown was completely unaware of the building’s place in British electronic music history when she bought the house.

“I used to drive past with my partner at the time,” she says. “We had a paintball business out here. We’d quite often see Daphne walking along the road, but we didn’t know it was her until we were buying her house. When we came to look around, it was jam-packed full of old tape machines and reels of tape and all sorts of weird contraptions she’d made. They emptied the place before we moved in, but there were a few bits left. We’ve got her set square and I think there’s a plug!”

Ron Morrow bought out Jenny’s former partner when they split up.

“We ended up buying the house by default,” he says. “We’d actually wanted to skedaddle, but it was almost like we couldn’t get away from the place. It was like fate.”

It wasn’t long after this that Tower Folly began to resonate with the sound of electronic music once again.

“We started putting on parties here in the 2000s,” explains Ron. “Mostly electronic stuff, with a few post-punk types from that time. The house has got an energy and it attracts people.”

And you really believe that?

“Oh, I think so,” he replies with a smile. “Things happened, multiple things in a row. We weren’t spooked by them, but it felt like being a passenger.”

He’s describing ghost activity, or at least unexplained phenomena, and the series of coincidences that forced the pair to stay at Tower Folly.

“Daphne was more into healing in the end,” notes Jenny. “We’ve got a typed poem by her somewhere. It’s called ‘Atlantis Anew’ and it’s all about sound-houses. The Francis Bacon novel relates to 17th century England, but Daphne’s poem is about healing people with sound in the future. At the end of her period of work, that’s where her focus was.”

Jenny disappears for a couple of minutes to dig out a copy of the poem.

“We have also sound-houses where we practice the healing powers of sound, where we analyse each human’s innate waveform and induce those harmonics to resonate when fallen out of sorts,” writes Oram.

The piece goes on to describe how people and animals are able to communicate and how criminals are put into a “harmless restful sleep” until they’ve come to their senses. It concludes:

“For here we excite by the subtle higher frequencies the inner consciousness of man, linking him in truth with the infinite timelessness of that still point where all is comprehended.”

After I leave Tower Folly, just before I hit the motorway, I realise I’ve left my digital recorder behind. I swing around the roundabout that leads onto the M20 and return to the oast house.

“She drew you back!” laughs Jenny, handing me my little piece of recording technology.

Once I’m on the road to London again, I switch on the radio. I tune into Radio 4 and they’re talking about Florence Cook, a famous 19th century spiritualist. The programme posits the idea that the world of spiritualism enabled women to follow their own pursuits within a domestic setting (traditionally a female realm) and allowed a sidestepping of gender roles.

I try not to get sucked into some kind of spooky crisis (no, Daphne Oram is not communicating with me via the medium of radio) as I drive to my next Oram appointment. I’m meeting Tom Richards, whose reassuringly practical doctoral research resulted in the building of the machine that Oram started work on in the 1970s as a distillation of Oramics. I’m going to try to my hand at Mini-Oramics.

Tom Richards’ PhD is both intriguing and essential reading. It’s 60,000 words of research into the technology of Oramics and the surrounding narrative of how Daphne Oram arrived at and developed the concept.

Tom’s background is in sound art and making electronic instruments. His output for the Nonclassical label, like the recent ‘Heavier Sideways’ EP, takes his homemade electronics and live radio interventions, plus a Soviet-era drum machine, into some fascinating experimental territories.

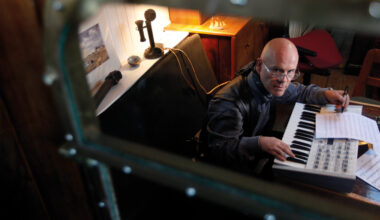

He first heard of Daphne Oram when a friend noticed an invitation to apply for a practice-based PhD at Goldsmiths College, which was looking for someone to research Oram and “build some stuff”. It was right up Tom’s street. He ended up using Oram’s extensive drawings and log books to make the world’s only Mini-Oramics machine, a working exemplar of the idea Oram was trying to perfect in the 1970s, but which was never realised. And there, in a spare bedroom in a terraced house in Peckham, south London, is Mini-Oramics 2020.

“It’s not really a replica,” says Tom. “Daphne never actually built a Mini-Oramics machine. There’s no evidence she got very far with it at all, but there was a design and an outline of it at Goldsmiths.”

Tom thinks she had wanted to commercialise Oramics and aim it at the education market – a Mini-Oramics in every school and university.

“It would have been very hands-on and immediate,” he says. “Bear in mind this was pre-MIDI, pre-computer-based timeline technology. I think the remarkable thing about Oramics is that it had this graphic and intuitive interface, with the advantage over tape being that pitch wasn’t related to speed anymore. Tempo and pitch were no longer linked in this medium and that was a big challenge to overcome with tape.

“I think she wanted the machine to become a standard de facto object in universities and music studios. It’s hard to say how far her ambitions lay with that. She was very motivated and she knew everyone in the electronic music world. If you look in the archives, there are letters to all kinds of movers and shakers in Europe and America. I think she would have liked it to provide a living for her and become something that wasn’t just a one-off.”

What do you think stopped that from happening?

“I think it was down to people not really taking her seriously, partly because of the misogynist old boys’ club of the time. That’s not something I really dwelt on in my PhD because it’s difficult to prove and quite subjective. She had a few supportive people in the worlds of electronics and technology, but she had trouble breaking through the glass ceiling in places because people didn’t have the vision she did.

“Another problem was the original Oramics machine itself. It was quite hard to demonstrate for a number of reasons and there is evidence that she had trouble keeping it running reliably. It didn’t help that it was in the middle of nowhere in Kent and not really moveable, so if she wanted to demonstrate it to anyone, she had to convince them to drive to Tower Folly.

“There’s also the fact that, in the summer of 1966, she had some kind of breakdown or other health problem. It’s not completely clear what happened. Then at the end of that summer, she fell out with her most important technician, Graham Wrench, and with her brother John, who had made the transport mechanism for the machine.”

Oramics never made it to market. Perhaps her 1966 crisis stymied it. Perhaps the idea had to be computer-based before it could work properly. Interestingly, the scrolling timeline concept, which was at the heart of Oramics, forms the very basis of modern recording technology. Oram did teach herself to write computer code in the early 1980s and tried to port Oramics into Computer Oramics. Her computer and some disks are at Goldsmiths and Tom is hoping that someone with specialist knowledge will step forward and investigate whatever is on them.

But time marched on past Tower Folly. With the advent of MIDI, computer sequencing and hard drive recording, all of the innovations in new music technology came from Japan and America, not from Kent.

“You can see Oramics as a sort of evolutionary dead end, but also a missing link,” says Tom. “It’s not true to say that Daphne didn’t have a major influence, even though her machine didn’t achieve what she wanted it to. She taught and interacted with so many of the great and good of electronic music in that period and I think she was responsible for introducing many enthusiasts who later became bigger names through these technologies.”

Tom lets me have a go on his Mini-Oramics. Writing music with it is a strangely magical experience. It has a mechanical/light-controlled sequencer, envelope generator and pitch modulator. With a marker pen, you draw envelope waveforms directly onto a clear film, which is lit from underneath. There are two oscillators, so you can draw two sets of envelopes. Notes themselves are applied in a way that’s similar to the piano roll view in a program like Logic or GarageBand and there’s another section where you can add vibrato. Scrolling is achieved mechanically, with the roll of film pulled from a large reel through the device housing the light sensors and onto a take-up reel. The sensors convert the information they read into voltage control and that’s sent to the synthesiser, which is in a separate box.

My attempt at Oramics is short and rudimentary to say the least – three deep notes that wobble slightly – but it’s a thrill. If left alone with it, I would have gone mad and scribbled all kinds of input data, cackling wildly as the machine spat out my doodled composition, but I felt slightly inhibited, like pootling around a racetrack at 30 mph in a supercar with its designer in the passenger seat. When Tom takes the wheel, he loads up a version of a Beethoven piece he’s been working on. It’s based on Wendy Carlos’ adaptations which she created for the score of ‘A Clockwork Orange’ and the Mini-Oramics bursts into life, producing several minutes of extraordinarily complex and bewitching music.

“If she’d managed to bring out the Mini-Oramics in 1972 or 1973, it would have been a really remarkable thing, a total game-changer,” says Tom. “But I think the more time that passed through the 1970s, the less of an impact it would have had and I think MIDI would have killed it.”

By the way, if you want to buy a Mini-Oramics machine, Tom would be more than happy to build one for you. But be warned, it will take a while and it won’t be cheap.

Isobel McArthur is an actor and playwright. She wrote a play called ‘Daphne Oram’s Wonderful World Of Sound’ and took the title role for a tour of Scotland in 2017. The play jogs through Oram’s life story, from childhood to Oramics and beyond, and employs a startling range of theatrical devices and techniques. The show was live scored by musician Anneke Kampman from the electronic duo Conquering Animal Sound.

“If I had to sum up the play, it’s essentially a masterclass delivered from beyond the grave,” says Isobel. “We created a liminal space in which Daphne would speak to the audience and then step into the reality of her life at different points. That’s how it played out.”

Did Isobel get to know Daphne Oram by playing her night after night?

“It’s odd… that process of researching and spending so much time with a person you’ll never meet,” she says. “I did feel a wee bit like I was communing with a spirit on a daily basis, to be honest!”

I tell her Oram would most likely appreciate that.

“Well, this is the thing. I’m probably using that quite spiritual language because there’s so much of the occult or the mystical about her, not only in her origins, but in the work that she went on to do.”

What did you make of that side of her?

“I think it’s fantastic. It appeals to me because of the world I come from, where the imagination wins out over fact, over anything else. That’s what we’re trying to achieve when making a good piece of theatre.”

Did your instincts tell you who Daphne Oram was?

“A process like this is a simplification of a person – of a messy and an inconsistent personality and life – but then also a magnification of those aspects that seemed significant to me, as a writer and performer,” explains Isobel. “In Daphne’s case, that’s her being really funny, really talented, really principled, really clever, really dedicated and really resilient, as well as the kind of impossible aspect to her story. From the outset, it’s clear she’s brilliant and gifted in many ways, but the odds are stacked against her.

“It was only because she had this amazing determination and she always put the music first that she was equipped to survive the things she did and still accomplish what she did. Just because there’s a lengthy period in an oast house and there isn’t a husband in the picture, it doesn’t mean she couldn’t hold a conversation. She was not some recluse. She was liked, she had a social circle, she had loads of friends, she was charming and good company and she was great at a party! This is what we know about Daphne anecdotally, but it’s almost a ‘neater’ telling of the story to go, ‘Total oddball, couldn’t look anyone in the eye, just stared at reel-to-reels all day’. It’s completely reductive in my opinion.”

In all my travels around Oram, it’s a film of a live performance of ‘Daphne Oram’s Wonderful World Of Sound’ where she comes to life the most vividly. Her vibrations are clearly still resonating around Tower Folly and, albeit perhaps fancifully, in the circuits of Tom Richards’ Mini-Oramics machine. Looking through the papers and photographs in the Daphne Oram Collection at Goldsmiths and holding her 1658 edition of Francis Bacon’s ‘New Atlantis’ has been a real privilege. But seeing Isobel McArthur channelling this remarkable woman on stage – pointedly the only woman on stage – and bringing her to life in her charismatic prime, rounds out all of these experiences to the point where I feel I’ve almost met Daphne Oram in person.

Daphne Oram suffered a stroke in 1995 and lived out her last years in a nursing home. When she died in January 2003, Oramics had been largely forgotten and her role in shaping electronic music in the UK was diminished, not least by Desmond Briscoe’s 1983 book, ‘The BBC Radiophonic Workshop: The First 25 Years’, in which she is barely mentioned.

Inevitably, there is so much more to this story. Oram’s early life in her childhood home, where she and her brothers wired up the radio to broadcast her playing piano around the house, the spiritualism in the front room, the details of her achievements at the BBC, the travails and goats and cats of Tower Folly, her truly sui generis 1972 book, ‘An Individual Note Of Music, Sound And Electronics’, her weekly electronic music classes at Canterbury Christ Church College between 1982 and 1989, which coincided with her computer decade, when she taught herself how to code…

But the last words should go to Daphne Oram herself. In 1994, the academic music journal Contemporary Music Review published an article she wrote called ‘Looking Back… To See Ahead’, in which she ruefully eyes her own past and expresses great enthusiasm and hope for a future which she had helped to bring about, but must have known she wouldn’t be part of.

“Women of substance, probably in all walks of life, found the late 40s and the 50s difficult,” she wrote. “On the musical scene, some of the various groups of establishment male musicians found it to their advantage to ignore women, treating them as if they were just not there. They were not to be noticed for almost a generation…

“Taking a cue from the novelists of the 19th century, could the woman composer of today retreat to the home and successfully produce the final complete musical product, projecting it directly to an appreciative market? Yes, at last the facilities are becoming available, and will be comprehensively here by the turn of the century, I think…

“But the home computer is today a very sophisticated machine, getting better every year. How exciting for women to be present at its birth pangs, ready to help it evolve to maturity in the world of the arts. To evolve as a true and practical instrument for conveying women’s inner thoughts, just as the novel did nearly two centuries ago…

“We may need female administrators and female music critics up and down the country, female recording producers and electronic engineers to organise the modem optical fibre communication lines and the digital studios…

“In a few years, we could be independent and standing on our own feet as successfully as the female novelists. Good luck to them… and to us.”

For more information, visit daphneoram.org