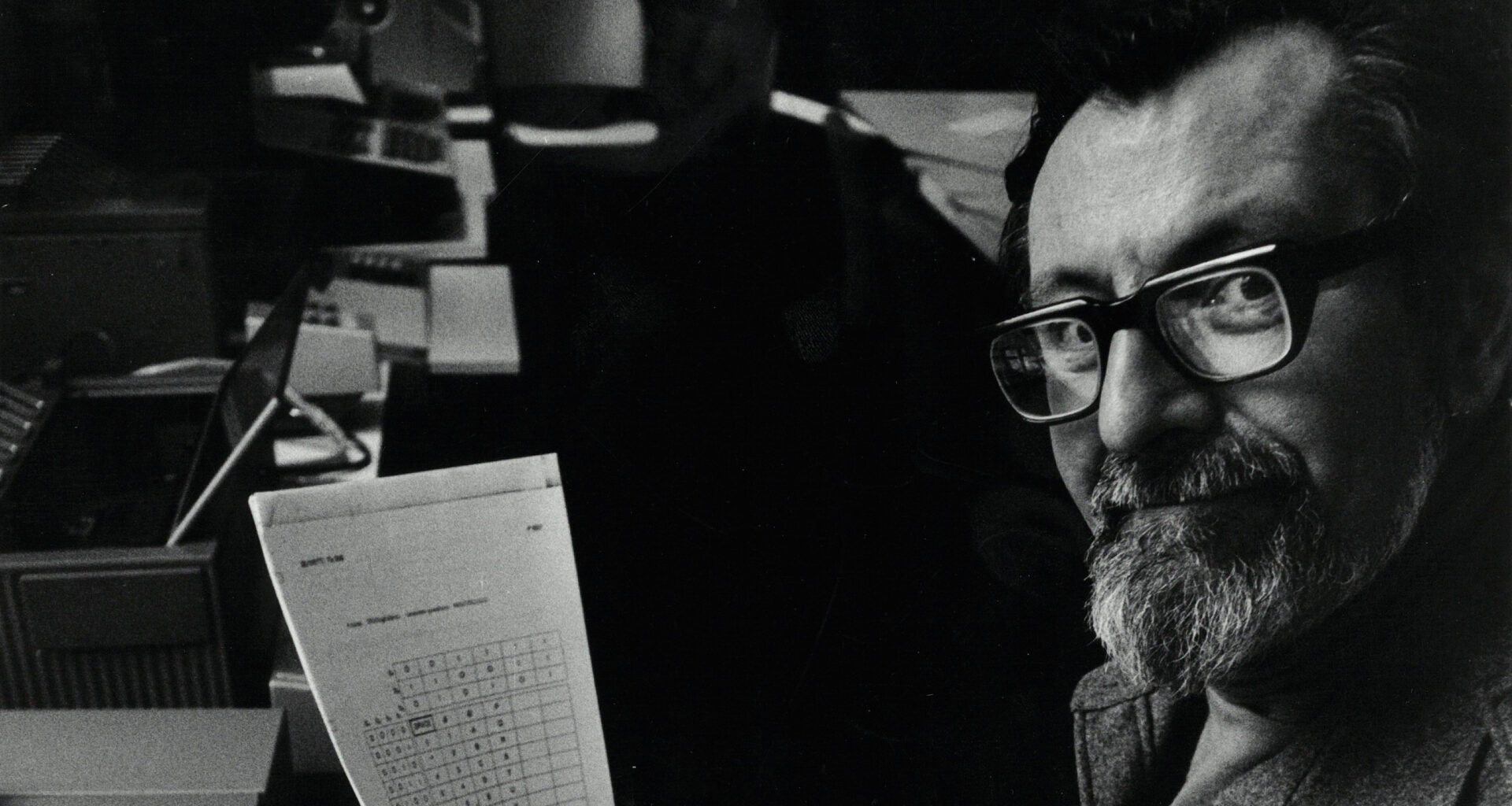

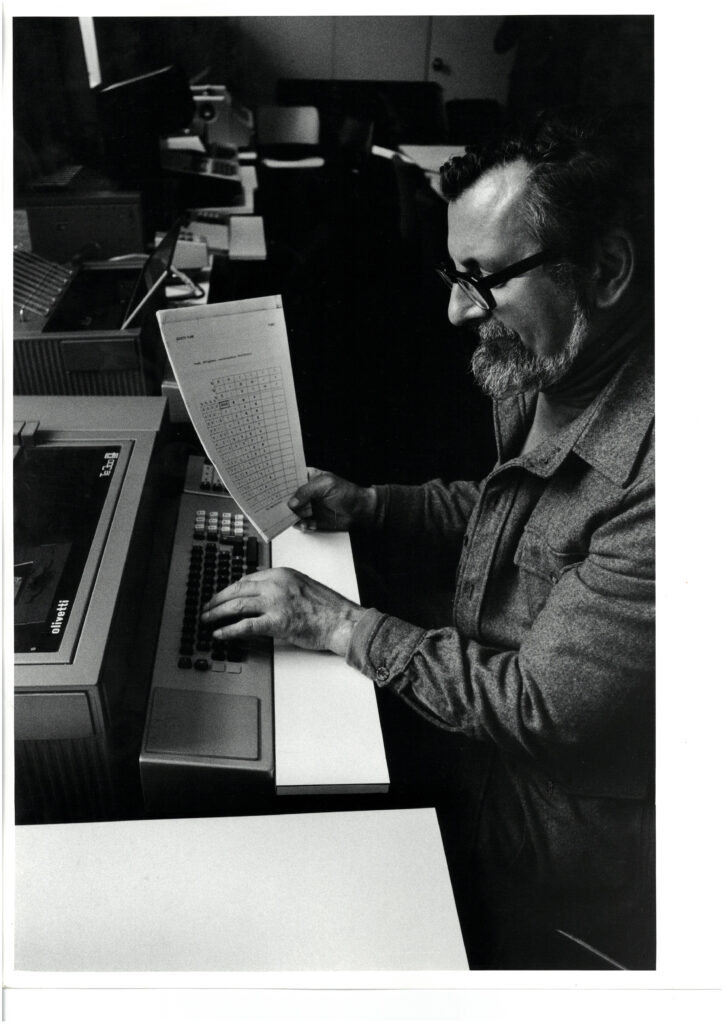

Tristram Cary, avant-garde exponent of all things EMS

Tristram Cary was born in May 1925, the son of novelist Joyce Cary. Learning piano from the age of five, music was always part of his life. In 1943, when he turned 18, he volunteered for military service and worked first as a wireless mechanic, and then as a radar engineer.

Immersed in a world of 1940s valves and oscillators, it was while working at this sharp end of communications technology that he heard about magnetic tape, which the Germans had developed, and was already thinking about the possibilities of tape editing and splicing as a way of creating music.

After the War, he completed the degree he had barely started when he joined up, and then studied composition at Trinity College, London. In the early 1950s he worked part-time at a high-end hi-fi shop in London, and started to establish himself as a composer while putting together his private electronic music studio from the same bits and bobs that Peter Zinovieff was collecting from the surplus shops on London’s Lisle Street.

Like Zinovieff, Cary was repurposing this gear, which was often bought unused in mint condition, engaging in what we might now call hacking or circuit bending to create music making units out of test equipment. By 1952, Cary had his own tape machine, a Bradmatic, from the company who later made the Mellotron, and with it, his studio was becoming a serious facility, and was possibly the first in the UK.

His first widely known work was the score for the 1955 British film classic, ‘The Ladykillers’. Featuring a lively series of works for an orchestra, it’s full of crowd-pleasing moments and was perfectly tuned to the requirements of the on-screen action. In the same year, Cary also produced a piece of tape music for a BBC radio play, ‘The Japanese Fisherman’, about the H-Bomb tests of 1954. Cary’s soundtrack, a suitably terrifying sonic collage of drones and noise, was the BBC’s first fully electronic score, some three years before the establishment of the Radiophonic Workshop.

This duality in Cary’s work, producing mainstream orchestral music for film and television, while also creating pioneering avant-garde electronic and tape music, would be a defining characteristic of his work life. The TV and film commissions paid the rent, but developing electronic music was his solitary passion. Bringing them together with his own work and the founding of EMS would be his massive creative contribution to electronic music.

Building up his studio at home in Fressingfield, Suffolk, by 1966 he was well established, with more film commissions under his belt (among them the score to the film version of ‘Quatermass And The Pit’, which was due for release in 1967), and TV work that included ‘Doctor Who’. He was also teaching at the Royal College of Music, and set up an electronic music studio there. And then he received a phone call.

“It was a chap called Peter Zinovieff,” recalls Cary in his fascinating unpublished memoir, which Electronic Sound has been given access to by Tristram’s son, John. “He told me he was involved in developing an electronic music studio at his house in Putney, and would like to meet me.”

At first, Cary was a little wary. He felt he was being invited to join a group, which at that time included Zinovieff, Brian Hodgson and Delia Derbyshire.

“I said cautiously that I was not much of a joiner, preferring to work on my own,” he writes. But he went to visit Zinovieff at his home and was impressed by what he saw. “One glance told me that a great deal more money had been spent in Putney than on my own studio.”

He also noted that more finished work emerged from Fressingfield than it did from the Putney studio and recognised David Cockerell, who had been building his own versions of Bob Moog’s synthesiser circuits, which had been published in a technical journal, as the brilliant engineer he was.

The first Moog modular systems soon started appearing in the UK, and Cary could see how the voltage-controlled oscillators and filters would be a fantastic addition to his studio. But the cost, around £200 per module (around £3,000 today) was prohibitive.

The solution to this problem started to develop: perhaps together with Zinovieff and Cockerell they could design and build their own synthesiser.

When Don Banks, an acquaintance of Cary’s, asked if they could build a box that would enable him to incorporate electronic sound into his own TV and film compositions, they readily agreed. With a budget of £50, they put together the one-of-a-kind rack-mounted Voltage Controlled Synthesiser 1, better known as the VCS 1.

Almost immediately they were caught up in the momentum of designing an improved version, which led to work on what would become the VCS 3. Zinovieff had recently discovered a cache of war surplus matrix boards, which gave the trio an elegant solution to what they saw as the problem with Moog’s patching system.

“With the Moog machine,” writes Cary, “if the patch is of any complexity, the front panel becomes a mass of long and short patch cords all over the place – sometimes it’s hard to get at the control knobs behind the ‘knitting’.

“We decided to use a completely different type of patch, with no plug and socket connections and no cords. This is a ‘pin matrix’. The very compact pin matrix was both much smaller and much tidier than PO [Post Office] patching, so the whole synthesiser could be smaller (and cheaper, we hoped) than Bob Moog’s machine.”

The designs and concepts of the new synthesiser were discussed over drinks in The Cedar Tree pub on Putney Bridge Road, after which Cary designed the iconic VCS 3 box, using black painted wood for the casing, and white formica for the front panels. In the lower panel he mounted the pin matrix, a joystick and a tray to hold the pins, leaving the upper panel blank for Cockerell to place the circuit boards and controls. Cockerell filled the prototype with the necessary circuits and knobs, and within days the trio had a working prototype.

They showed off the VCS 3 prototype at Zinovieff’s studio to various visiting composers, musicians and other interested parties, even lending it out – albeit reluctantly – every now and then. The next step was to put the synthesiser into production, a complicated process that required finding a factory that was able to manufacture it at commercial scale.

And then, it seems, Cary ducked out of EMS activities for a while, and was less involved in this phase of the machine’s development. He was only able to turn up at Deodar Road occasionally because of his composing work, which included music for a documentary about the op-art painter Victor Vasareley (a painting of his was used on David Bowie’s eponymous 1969 album, and his work also graced sleeves by Xenakis and Stockhausen) and his teaching work at the Royal College Of Music.

As manufacturing got under way, Cary took on the role of developing the company’s customer base among what he called “serious” composers, and music departments of universities. He would also write the first manuals, which he brilliantly called “literate handbooks and other paper software” in his memoir.

While the VCS 3 found favour with composers and universities alike, Cary mentions that “a succession of young men with interests in the field of rock and pop groups were brought in to interest such groups in the synthesiser (and a few, such as Pink Floyd, became serious users)”.

In 1969, Cary composed several important electronic and tape music pieces. ‘Narcissus’, a “tape plus score”, was written for flute and two tape machines, and predated the work of Fripp and Eno in the mid-70s. The flautist was recorded on one track, which was then turned over and played back, while recording the flautist again, this time with the first recording added. The overdubbing process was repeated, with operators changing the machine speeds and shifting the recordings up and down an octave until there was a mass of flutes.

Cary also composed what he considered his best (and most complex) piece of tape music, the 14-minute ‘Continuum’. In his memoir, he describes the frustration of trying to create a decent mix of the piece from 10 different tracks all playing at the same time. It builds to the point where he was kicking doors in anger before chucking it all in and going down the pub.

The laborious nature of tape music was one of the drivers for Zinovieff’s interest in computers. He found the process of tape editing irritating beyond endurance, and wanted to harness computer technology and voltage control to do the job for him.

In 1969, Cary undertook a major choral work. The Director of Music at the University Of East Anglia contacted him to say if he was to come up with a piece that involved instrumental and electronic music it would be “considered for performance”.

He immediately began work on a post-nuclear holocaust concept set 100,000 years in the future. In his vision, the Earth is bereft of life, the only evidence of habitation being the remains of concrete buildings and roads. A group of scientists from an alien planet discover Earth, and are able to look back at its history through some clever piece of technology, but are unable to work out why humanity wiped itself out.

Once complete, he called the piece ‘Peccata Mundi’ (from the liturgy ‘Agnus Dei’, a sung or spoken invocation to the Lamb Of God; “Lamb of God, that takes away the sins of the world, have mercy upon us”).

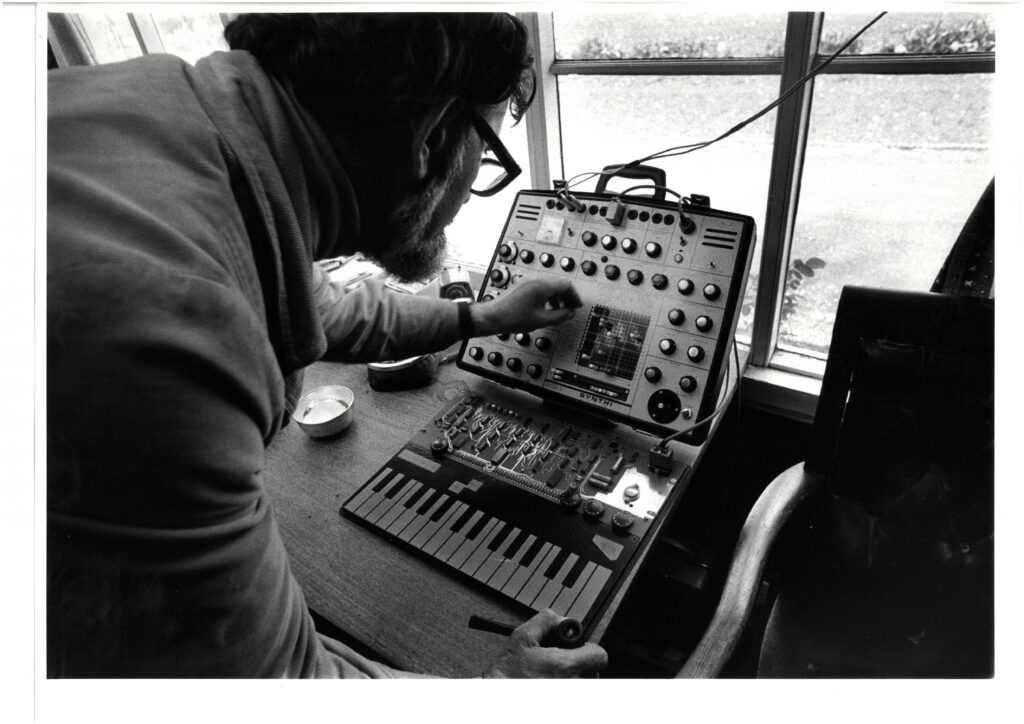

Life was hectic as the 1960s came to a close. The composing was a top priority for Cary, but EMS was growing apace. They were already developing a second synthesiser in the Synthi A, and that would soon be followed by the Synthi AKS, which added a touch capacitive keyboard and a digital sequencer and bundled the lot into a briefcase like some kind of James Bond synth.

Cary and Zinovieff headed to New York with the AKS to explore the possibility of rustling up more orders.

“We had a little difficulty at Kennedy, where a suspicious customs man thought the AKS might be a weapon of some kind,” remembers Cary, “He wouldn’t believe us at first when we said it was a musical instrument, and we could only convince him by actually plugging it in and playing him a tune.”

The demos for interested parties were a bit of a disaster, the humidity alone was enough for the synth to start playing itself and then malfunctioning. They tried keeping it in an airing cupboard at New York’s Cornell University between demonstrations, but the AKS proved a temperamental beast.

Once back in the UK, the keyboard was redesigned and the glitches ironed out, and when it was finally launched, the Synthi AKS was yet another success for EMS.

In 1970, Cary was invited onto the board of the Performing Rights Society as an expert on electronic music, and to particularly focus on the problems of copyright around tape music. But it’s clear from his writing about this time that he was dissatisfied with his standing as a composer. He felt his catalogue was “very thin and poor for a composer of my age”, and there was no doubt that his extracurricular activities at EMS were costing him time that he might otherwise have spent on composing.

In 1973, he was lured away from the UK and EMS by an offer of a teaching post at the University Of Melbourne as visiting senior lecturer. He then became visiting composer at the University Of Adelaide 1974. The opportunity came about as a result of him visiting Australia to demonstrate EMS equipment to universities. He died in Australia in 2008, where he was revered for his contribution to Australian culture.

Tristram Cary has been described as the father of electronic music, and while that’s an epithet he shares with several others, he has been somewhat overlooked in the UK and deserves to be more widely recognised in the country of his birth for the two decades of pioneering work he put into the development of electronic music.