‘The NID Tapes’ is an extraordinary compilation of early Indian electronic tracks recorded at the National Institute of Design in Ahmedabad between 1969 and 1972. Sound artist Paul Purgas relays the story of how he uncovered these long-forgotten gems

It all started with a tweet. In 2016, the London-based multidisciplinary artist Paul Purgas unsuspectingly clicked on a link that would change the course of his life forever. The article within said tweet – ‘Subcontinental Synth: David Tudor And The First Moog In India’, written by Alexander Keefe – was originally published in 2013 and had been retweeted by a music journalist Purgas followed. It told the labyrinthine tale of how a Moog synthesiser ended up at the National Institute of Design (NID) in Ahmedabad, India, in 1969.

For Purgas, a British-Asian electronic musician who’d come from an architectural design background, it seemed like a no-brainer to pursue a narrative that potentially connected strands of design history, South Asia and electronic music.

“It just seemed like a fascinating story,” he enthuses, sitting across from me in an elegant bar tucked away in the basement of London’s Somerset House, where his studio is located. “So I decided to go to Ahmedabad and learn more – I’d been touring with my band Emptyset and I had a lot of air miles piled up.”

So in 2017, he made his first trip to India to find out more.

This month sees the release of double album ‘The NID Tapes: Electronic Music From India 1969-1972’ on the State51 Conspiracy label. Curated by Purgas, it features recordings from American experimentalist David Tudor, Indian classical musician Gita Sarabhai and four all-but-forgotten electronic composers – Atul Desai, IS Mathur, SC Sharma and Jinraj Joshipura, who was just 19 years old when he joined the facility. The last surviving composer from the National Institute of Design, Joshipura is now living and teaching in Puerto Rico.

‘The NID Tapes’ is the culmination so far of a story that winds and twists, with Purgas’ accidental intervention crucial to uncovering a lost history of the country’s electronic avant-garde.

Since his first mission of discovery, Purgas has made a lauded BBC Radio 3 documentary, 2020’s ‘Electronic India’. There’s a book in November, edited by Purgas and published by Strange Attractor Press. And if that weren’t enough, there’s also a dynamic exhibition and sound installation curated by Purgas – ‘We Found Our Own Reality’ – which has made its way from Camden to Berlin and Glasgow and promises to keep moving.

While the projects that have sprung from the source keep proliferating, we must start with the synthesiser, which became an unobtainable object of Purgas’ infatuation.

“I naively thought I could find that Moog,” he tells me, referring to the model that ended up at the NID in 1969.

In truth, he came close, although it looked as if he might ultimately go home empty-handed.

“I’d spoken to Moog and had been given their blessing to restore the synthesiser if it could be found. So I went out to Ahmedabad and made contact with the owner, who was a former faculty member.”

The owner, who has since passed away, was not as forthcoming as Purgas had hoped, and actually seemed suspicious of his motives. The instrument was apparently resting in a home for stray cats and dogs on the outskirts of the city near the airport.

“I’d been told there were termites living in it, but it was in good health,” says Purgas. “So it was a complex and strange encounter.”

Having failed to secure the Golden Fleece, he decided to look through the archives at the NID with a view to finding photographs.

“Digging more closely, I found a book of handwritten notes from the late 1960s,” he remembers. “There was a note that said, ‘Tapes for David’. It immediately piqued my interest, so I asked the lady working there, ‘Can you get these tapes?’.”

A cupboard was located, and out came the motherlode.

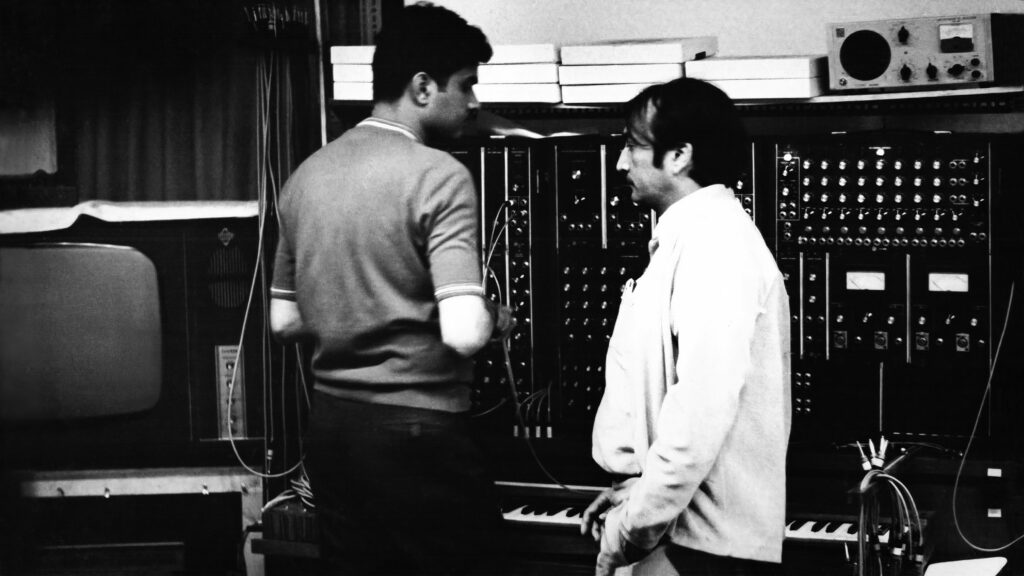

India’s first Moog synthesiser arrived in Ahmedabad in several wooden crates from Trumansburg, New York, in 1969. There was no keyboard attached at the outset, although it did have a linear ribbon controller. The avant-garde composer and pianist David Tudor took receipt of the machine and installed it at the NID electronic music studio he had established there that same year.

Tudor – who is said to have been ambivalent towards Moogs and to Bob Moog himself – is perhaps best-known as the musician who performed many of John Cage’s works, including ‘4’33”’. He became an important figure in avant-garde sound design following his involvement with the Pepsi Pavilion at Osaka’s Expo ’70 – allegedly to Cage’s chagrin. Purgas has found that people in his own milieu are either Team Cage or Team Tudor.

“I definitely lean more towards Tudor,” he reveals. “And actually, the more I’ve learned about his story, the more I’ve discovered about him keeping in touch with some of the composers at the NID – right into the 1980s. It seems he was very authentically invested in supporting that scene and culture, which I think is a beautiful thing.”

The Moog would become the centrepiece of a faculty where Indian electronic music was effectively born.

“What I hadn’t realised from reading the initial article was actually the magical context of the NID,” says Purgas. “The idea of this type of modernist architecture and radical pedagogy that you associate with the Bauhaus. Seeing that in India was exceptionally mind-expanding.”

This freedom in the name of discovery was contrary to most Westerners’ perception of India at that time, which was exacerbated by The Beatles visiting the Maharishi for an extended stay in 1968. Seeking spiritual enlightenment with the tools of ancient religious practice could be regarded as retrogressive. A Moog synthesiser, on the other hand, represented a mythical future rather than a mystical past, and fired the imagination at a time when space exploration was becoming a reality.

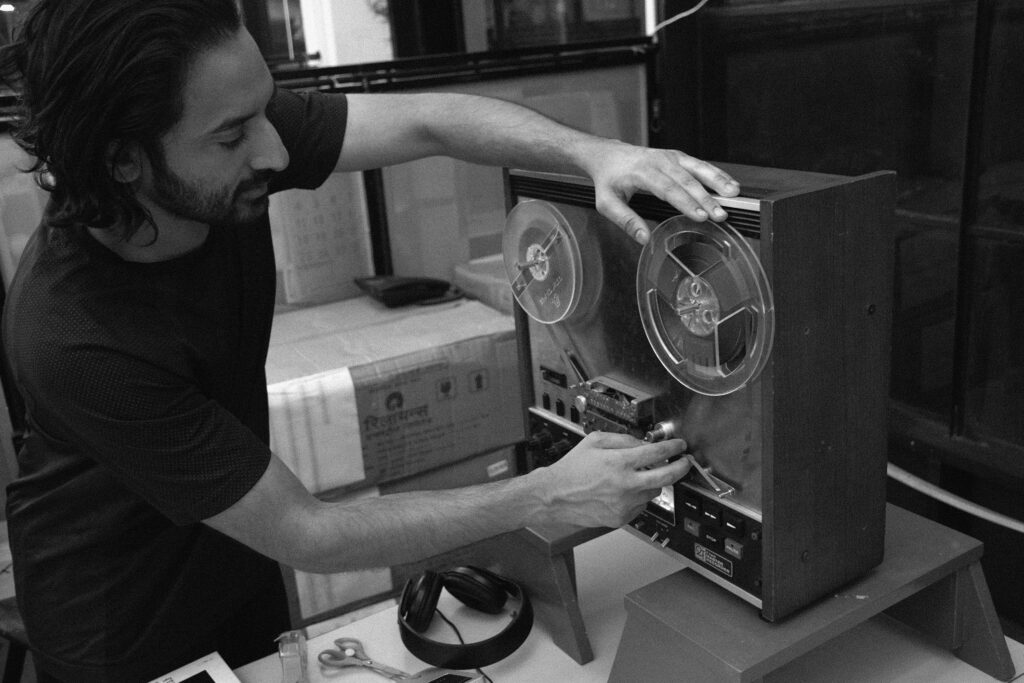

Fast forward to 2017, and compositions that had been carelessly discarded – not thought important enough to preserve for posterity – and presumed lost were suddenly presented to Purgas in several towering piles. He could only imagine what might be sonically imprinted on these magnetic spools, and his initial excitement was soon overridden by an urge to preserve everything he had found.

“Realising the value and importance of the material, my first instinct soon switched into the mode of conservationist,” he recalls. “I felt I had a responsibility to learn how to preserve and restore these tapes. This is essentially the electronic music culture of a billion people.

“So I came back to the UK and contacted the British Library Sound Archive, who were incredibly generous and gave me a lot of advice and feedback. I actually took a whole year to learn tape conservation with them before returning to India in 2018 with my own TEAC tape deck, a food dehydrator like an oven to bake the tapes, and splicing tape – the whole kit – in order to go and do it myself.”

That year of preparation and delayed gratification turned out to be worth it when Purgas had finished restoring the tapes and finally got to hear what was on them. Which track spoke to him the most?

“The one that jumped out at me was one of the final compositions at the studio by SC Sharma, simply called ‘Dance Music’,” he says. “It’s a series of three compositions that are a kind of rhythmic proto-techno from September 1972. When I first picked it up, it fell apart in my hands because it was about 100 tape edits stuck together with Sellotape that had lost its adhesion. So it took me almost a day to reassemble that reel. To hear that coming out of 1970s India was just magic.”

Geopolitical forces largely enabled the NID, and ultimately it would be geopolitical forces that closed it down in its original incarnation before it had really begun. Funding for the school had been provided by New York’s Ford Foundation and it was run by the Sarabhai family – well-connected industrialists who’d staunchly supported Mahatma Gandhi’s campaign for Indian freedom from British rule (the country gained independence in 1947). The generation of Sarabhais following these peaceful insurgents had been ingrained with a taste for radicalism and altruism.

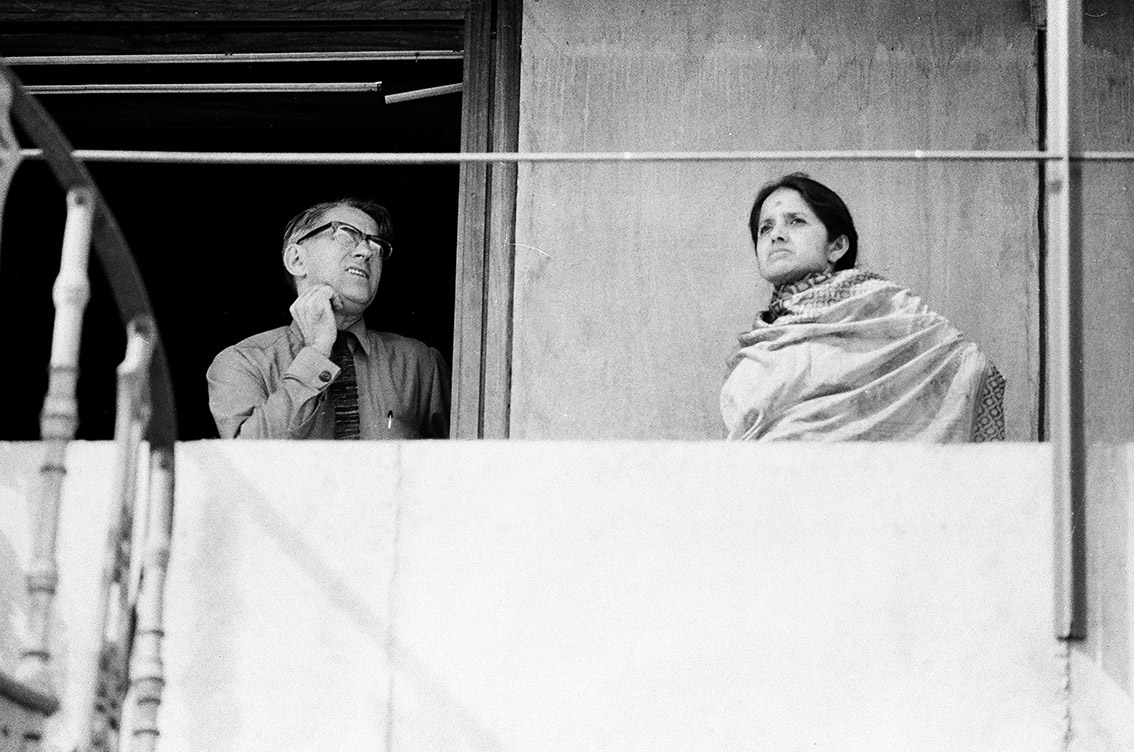

In 1961, Gira and Gautam Sarabhai – musician Gita Sarabhai’s siblings – helped establish the NID in accordance with recommendations from The India Report, commissioned by the country’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru and prepared by 20th century modernist design titans Charles and Ray Eames. As a young country recently emancipated from British colonial control, India was finding its way as any free-spirited teenager might, with experimentation the order of the day. A technocratic revolution beckoned, or so it seemed at the time.

Gita Sarabhai, meanwhile, forged strong links with the post-war avant-garde in the US. In the mid-1960s, she learned the rudiments of Western musical theory and 12-tone serialism from John Cage. In exchange, Sarabhai introduced Cage to Indian classical music and philosophy. Their close association would inevitably lead to an acquaintance with Tudor.

A honeymoon period ensued within a pedagogical programme pitched somewhere between the Montessori method and the Bauhaus. Anomalous though the NID sound studio was – situated in a design school as opposed to the radio-based Studio D’Essai, the Westdeutscher Rundfunk or the BBC’s Radiophonic Workshop – its modus operandi of sonic exploration was broadly the same. Jinraj Joshipura was looking beyond trying to incorporate the oscillations of the Moog with traditional music, and instead was considering ways in which electronic music could communicate with animals or send signals to submarines.

This brief rush of creativity was to be short-lived, however. Funding from foreign sources, including the Ford Foundation, subsided and the administration came under scrutiny from the Indian government. As the department declined, it looked as if Joshipura would transfer to the Rockefeller Music Research Centre in San Diego to study sound synthesis after a recommendation from Tudor, but he was talked out of it by his pragmatic father, who told him to continue his architectural studies. Yet his Moog explorations were far from over – his fascination persists to this day, much to Purgas’ delight.

“I went into the project believing everyone had passed away, so discovering Jinraj was beyond magical,” says Purgas. “He is an incredibly passionate person, still very interested after almost 50 years’ absence from electronic music, and now very much reinspired. It’s a personal dream to reconnect Jinraj with the Moog and to try to get him to return to making electronic music. To me, that would be a really beautiful end to the story, and in a way that would complete the circle.”

The story doesn’t end there, either. As mentioned earlier, Purgas’ exhibition ‘We Found Our Own Reality’ – a National Institute of Design soundwork located within a configuration of architectural and design components – may soon be coming to an art space near you. There are echoes of the NID in a “topographic framework referencing modernist architecture as well as India’s powerful textile industry, and South Asian ancient religious and mathematical traditions”.

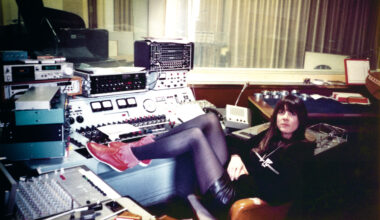

Alongside the installation will be a series of one-off performances connected to the original source material. Earlier this year, at Silent Green in Berlin, Purgas played a specially hired Moog Model 10 – offering a functionality as close as possible to the nascent Moog at the NID – with collaborative contributions from filmmaker Imran Perretta and rising producer Nabihah Iqbal.

Purgas talks at length about seeking out later works by SC Sharma and his hopes of finding a lost soundtrack by Gita Sarabhai for Akbar Padamsee’s 1969 film, ‘Events In A Cloud Chamber’. But it occurs to me that he’s far from finished with subcontinental synthesis or indeed the NID.

“I’m now entangled for life,” he admits with a laugh. “And I still feel bound to the Moog itself as an object. So I keep an eye on its trajectory and its care.”

‘The NID Tapes: Electronic Music From India 1969-1972’ is released by The State51 Conspiracy