Alexander Tucker’s latest work is a posthumous collaboration with Keith Collins, Derek Jarman’s former partner. The result is a touching homage to the iconic filmmaker and the inspiring landscape around Dungeness nuclear power station in Kent, where Jarman famously lived during the final years of his life

“Dungeness is at its best in the golden light of the summer. Twilight here is like no other. It lingers in a perfect calm.” Derek Jarman, ‘Derek Jarman’s Garden’, 1995

Geographically, Dungeness sits in Romney Marsh, an area of coastal Kent in South East England. It’s a place unlike any other, dominated by a vast shingle beach and bordered by a decommissioned nuclear power plant. Dotted with small, wind-battered fishing huts, it’s a remote, alien landscape, dubbed the “fifth continent” by Richard Harris Barham in ‘The Ingoldsby Legends’ (1837).

Located within that bleakly beautiful terrain is a small house, its weatherboarding tarred a resolute black, its window frames a cheery yellow. This is Prospect Cottage, acquired in 1987 by artist, filmmaker, writer and gay rights activist Derek Jarman, which he shared with his partner Keith Collins. Collins was forever by Jarman’s side in his final years. He organised Jarman’s life and commitments, protected him from savage media criticism and gave him stability in the face of hopelessness. After Jarman died in 1994, Collins maintained the house and gardens until he himself passed away in 2018.

In 1991, a young Jarman enthusiast, fine art student and future sound artist called Alexander Tucker walked past Prospect Cottage with his father and, through a window, spotted Jarman writing at his desk. Despite Jarman’s general fondness for unannounced visits by fans, Tucker decided against knocking on the door.

A few years after Jarman’s death, Tucker befriended Collins. They worked together on a BBC Radio 4 programme about Jarman and always intended to collaborate again, but Collins’ untimely passing thwarted those plans. Instead comes an album titled ‘Fifth Continent’ – a poignant tribute to Collins, filled with sounds created in the very room where the younger Tucker had watched Jarman working over three decades earlier.

“I leave footprints for others to excavate.” Derek Jarman, ‘The Last Of England’, 1987

Over the years, either via his many collaborations or as a solo artist, Alexander Tucker has proven himself to be a dexterous and stylistically unpredictable musician, seemingly able to switch his instrument of choice at will.

“With everything that I play, I’m self-taught,” he confesses. “To me, instruments are just materials. I think it comes from my visual arts background. Instruments are like clay or paint – something for you to mould and meld. There are so many ways to re-form sound and to make sounds with objects.”

Tucker began working on his own in the late 1990s.

“I was doing noise guitar pieces,” he explains. “That was my first foray into solo work, and I got to know quite a lot of people in the experimental improvising scene, like Richard Thomas, Duke Garwood and Paul May. I lived in a house with them and we were always improvising together.”

As time went on and his sound palette grew, he decided to reserve the name Alexander Tucker for his solo work with guitar, pedals and electronics, adopting the moniker MICROCORPS for what he calls “more of a focused, experimental techno kind of thing”.

‘Fifth Continent’ exemplifies Tucker’s cooperative side, even if Collins was only posthumously present. In recent years, Tucker has worked with Astrud Steehouder and Luke J Murray (as NONEXISTENT), with Nik Colk Void (as Brood X Cycles), and has just finished an album with saxophonist Karl D’Silva.

“For the past few years, my main collaborator has been Daniel O’Sullivan in Grumbling Fur Time Machine Orchestra – a more experimental offshoot of our Grumbling Fur duo,” he says.

“One of the artists we’ve worked with a few times now is Charlemagne Palestine. That came about when Daniel curated a couple of days of Charlemagne performances at Cafe Oto in London. For the second day, Daniel and I added the extended techniques and drone aspects of Grumbling Fur.

“When I ask somebody to collaborate on a track and they send material back for me to work with, it feels like a precious gift. I’m really interested in collage and assemblage, which again comes from my visual arts background. I love cutting up different things and layering them together, then getting this really surprising picture or piece of music at the end.”

“Late night on [Hampstead] Heath. HB gone leaves me quite adrift.” Derek Jarman, ‘Smiling In Slow Motion’, 2000

Derek Jarman met Keith Collins at a 1987 Tyneside film festival screening of ‘Sebastiane’, his controversial, taboo-shattering 1976 debut feature. It was the piece that signalled his signature directorial style but also his capacity to divide audiences. i-D magazine accurately summarised Jarman as being “secretly admired as the film genius of his generation while publicly he is neglected by both audiences and financiers”. Collins would later appear in three of Jarman’s films – ‘The Garden’ (1990), ‘Edward II’ (1991) and ‘Wittgenstein’ (1993).

“Derek’s nickname for Keith was ‘Hinney Beast’,” says Tucker. “It’s a Geordie term of endearment. In Derek’s diaries, Keith is always referred to as ‘HB’. Keith used to call Derek ‘Fur Beast’ because he was very hairy.”

It’s possible to get a good sense of the intimacy that existed between Collins and Jarman through the latter’s frank and unswerving journals, ‘Modern Nature’ and ‘Smiling In Slow Motion’.

Rarely a diary entry goes by where Collins isn’t mentioned, either helping to pack suitcases, fixing something around the house, suffering another sleepless night thanks to Jarman’s tossing and turning, making him laugh on his bleakest and most despondent days, or bluntly cajoling him into decisive action when he simply couldn’t face creating.

You feel his presence but you also feel his absence, Jarman’s mood becoming introspective and pessimistic when Collins heads back to Newcastle or goes travelling with friends.

Dungeness was not unfamiliar to Jarman, and neither was Prospect Cottage. He had first seen it in 1986, while filming ‘The Last Of England’ – during which he was diagnosed with HIV – setting specific scenes within a landscape that struck him for its “otherworldly atmosphere… unlike any other place I had ever been”.

Later, in spring 1987, Jarman set off with Collins and Tilda Swinton on a fateful hunt for a bluebell wood around Dungeness. They never did find one, but Swinton spied a “for sale” sign outside Prospect Cottage, and Jarman swiftly bought it.

By the time of his HIV diagnosis, Jarman had grown weary of London. Prospect Cottage gave him somewhere to escape to, where the less frantic pace inspired him in a way that the capital no longer could.

With a lot of help from Collins, the cottage was repaired and extended, and its distinctive gardens – formal to the front, wilder to the rear, each filled with sculptures Jarman crafted from the ample flotsam and jetsam arriving daily on the beach – were laid out and maintained.

Developing and tending the garden he called his “Gethsemane and Eden” became Jarman’s main focus. Throughout his two volumes of journals, he talks about nurturing opium poppies or a climbing rose with considerably more enthusiasm than the film and book projects he was working on at the time.

“Oh my heart rejoices in the roar of the surf on the shingle. Marvellous sweet music it is to my ears. Oh what joy there is in the embrace of water and earth.” Derek Jarman, ‘Jubilee’, 1977

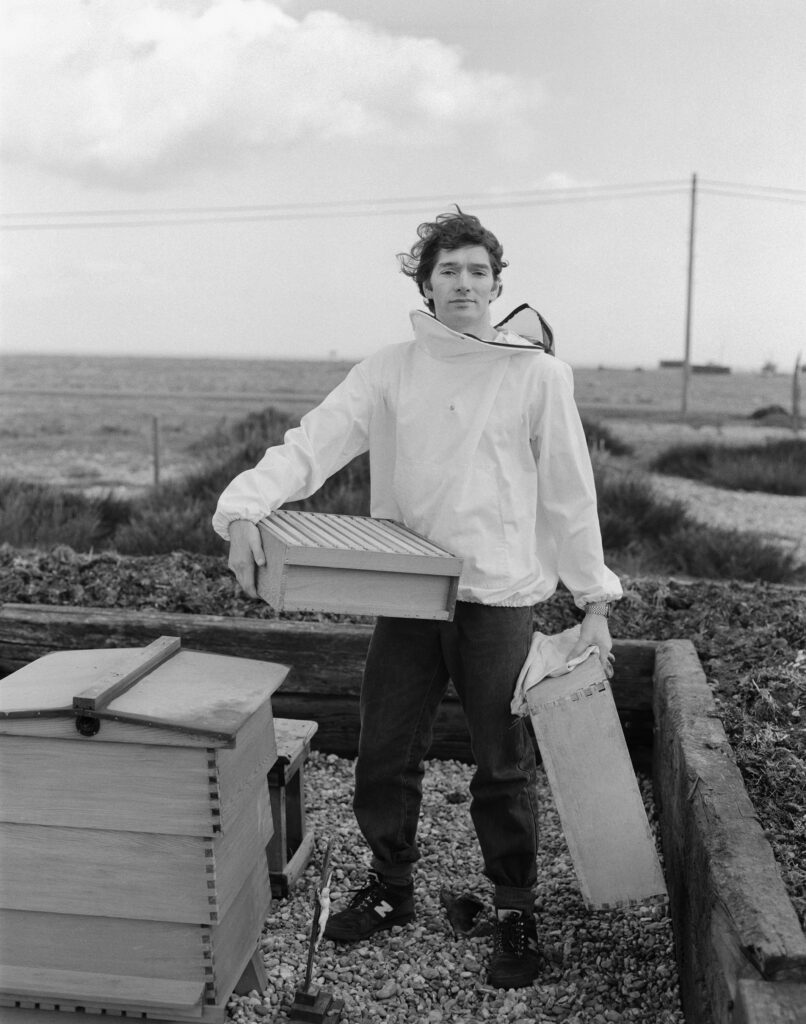

Tucker’s parents eventually moved to Dungeness, partly because of the number of times he and his father had visited over the years. By 1997, when they relocated, Tucker was in his second year at the Slade School of Fine Art in London, where Jarman had studied in the 1960s. He found himself visiting his parents often, and you can trace the genesis of ‘Fifth Continent’ to one such visit.

“It was a really nice, still autumn day, which is quite rare at Dungeness because of where it is,” he says.

“When the tide is out, the shingle bed drops sharply down, so when you look back up, all you can see is stones right up to the sky. I was down on the shore looking for driftwood and when I looked back I could see this silhouette of a guy. It was Keith Collins, who I recognised from Derek’s films. By that point, he had super-long hair and he was wearing Derek’s old coat. I just walked up to him and started chatting to him.”

Collins was living at Prospect Cottage, working as part of a fishing crew with a neighbouring family. After their first conversation, whenever Tucker was visiting his parents, Collins would invite him in for a cup of tea. The house was familiar to Tucker, principally from a 1991 Arena documentary, ‘Derek Jarman – A Portrait’ by Mark Kidel.

“I was obsessed with that documentary,” reminisces Tucker. “I probably watched it more than Derek’s films. So just to be able to go inside and see all the artworks, assemblages and objects was amazing.”

The pair became good friends, meeting when Tucker was in Dungeness or catching up in London after Collins relocated there. When BBC Radio 4 asked Collins to contribute to a 2016 radio documentary about Jarman, Tucker was his obvious choice to supply an audio accompaniment.

“Keith read a passage from Derek’s journal collection, ‘Modern Nature’,” remembers Tucker. “I supplied a prepared guitar piece recorded using wind and atmospherics at Dungeness. I put the mic from a broken digital 8-track into the body of the acoustic guitar, and my plan was to hold it up and get the wind to use it like an Aeolian harp. It has to be a certain speed to really work, and on that day it was too windy. So instead, I just laid the guitar on the ground, where the grasses started knocking against the body and touching the strings and playing it.”

Segments of that guitar piece appear again on ‘At Dungeness’, the final track on ‘Fifth Continent’, framing a moving narration by Collins recorded shortly after Jarman’s passing in 1994.

“The grandfather clock, which refused to work for weeks, now ticks through the day and night but has invented its own numerology – it strikes 13 quite regularly and then it’s anyone’s guess… five, eight, 10 and 13 again.” Derek Jarman, ‘Smiling In Slow Motion’, 2000

“Keith sent me an email in 2018,” remembers Tucker. “It said, ‘It’s bad news. I’ve just been diagnosed with a brain tumour’. In the same email, he asked me to sort out the cupboards of CDs at Prospect Cottage. He passed away later that year.”

Tucker obliged, visiting after his friend’s death to go through the music collection. While there, he met Collins’ husband, Garry Clayton, who was trying to restore the roof in spite of his grief.

Tucker had been planning a joint recording session at Prospect Cottage with Collins before the email made it clear this wasn’t going to happen. He was determined to create an homage to his friend, which is what ‘Fifth Continent’ ultimately became.

“In June 2019, Garry suggested I should bring some equipment down to Prospect Cottage,” recalls Tucker. “Keith was a voracious music fan and also made his own work, but he never intended to put it out there. I at least wanted Keith to have a release at some point. So I went down there with my modular system, a cello, a vocal mic and some recordings on a computer. I set it up at Derek’s desk and started recording processed cello and manipulated voices, just racking up layers of improvisations. It was a complete and utter thrill to work in Derek’s writing room, surrounded by those artworks.”

Clayton loaned Tucker a digital recorder that had belonged to Collins. Trawling through the archive, Tucker found the two emotional monologues which bookend the album – ‘In Smiling In Slow Motion’ and ‘At Dungeness’. Given how much of Collins’ and Jarman’s history was bound up in the walls of Prospect Cottage, it was important for Tucker to include field recordings made around it. He spent two days there, either capturing the natural ambience or improvising in the writing room. One sound that appears like a recurring motif on ‘Fifth Continent’ is the grandfather clock Jarman had installed at the cottage, its gentle positioning behind Collins’ voice adding a grave mournfulness to his words.

“I was always aware of it,” says Tucker. “It just made a great sound. I wasn’t even thinking of the passage of time or death.”

Back in London, Tucker applied his characteristic collage process, chopping up and editing sounds, inviting musician Kenichi Iwasa to add his own sonorous touch to the drone-heavy compositions.

“Ken plays with Exotic Sin and Maxwell Sterling,” he explains. “He sent me a bunch of improvisations, and then I cut up sections where he’s doing these almost impossibly long notes. His playing has a beautiful melancholia.”

It’s the confluence of these elements that gives ‘Fifth Continent’ its distinctive sonic and emotional impact. The album and its accompanying book, ‘Fifth Quarter’, are freighted with both remembrance and significance – for Collins and his devotion to Jarman, for Tucker’s friendship with Collins, for the unique magic of Prospect Cottage and Dungeness, and for Tucker’s own personal connections to the area.

“I walk in this garden, holding the hands of dead friends.” Derek Jarman, ‘The Garden’, 1990

The extract from ‘Modern Nature’ that Alexander Tucker and Keith Collins worked on in 2016 was about a life still being lived, whereas the ‘At Dungeness’ track is a thoroughly brutal exposition of Collins’ grief. It is what exists after the full stop of Jarman’s final entry in ‘Smiling In Slow Motion’, written on 31 January 1994, his 52nd birthday and a fortnight before his death: “HB true love”. Collins’ words were recorded in the epicentre of his loss, shortly after Jarman passed away at St Bartholomew’s Hospital in London.

‘At Dungeness’ might be unique to Collins’ experience, but it is relatable in a universal way. He vividly recounts putting on Jarman’s coat, hung expectantly in the Prospect Cottage hallway for its owner to wear when tending to the gardens. Collins finds a 20p piece in a pocket and is struck with sadness at the discrepancy between something so intensely personal to the friend he has lost and a mundane, quotidian, mass-produced coin.

“Everything I’ve ever made before this was a product of my world-building,” offers Tucker as we mull over the cruel sentiments of ‘At Dungeness’. “Most of the time, I make the work first and then think, ‘Where is this coming from? What’s been influencing me?’.

“With this album, it was much more considered,” he continues. “There was an intention. It was the first time that I had somebody else’s life in my care. ‘Fifth Continent’ became more of a reflection on the outside world, rather than just my interior. I can see now that my music has been moving towards this point for a while.”

‘Fifth Continent’ is released by Subtext Recordings