In a secret corner of Yorkshire, a man known only as Craven Faults creates epic modular synth homages to the dark, post-industrial uplands that surround him. Who is he? We really can’t say

’”I ve got friends who I’ve never told about this music,” smiles the man in the car park.

This is already an assignment like no other. I’m not allowed to reveal his name. Or even his exact location. In fact, until I’d specifically requested them from his record label the previous day, I’d been maddeningly unaware of these salient details myself.

There’s been a strong whiff of John Le Carré about this whole strange, undercover affair, and for several weeks I’ve entertained fevered fantasies of a covert rendezvous in overcoat and trilby, throwing chunks of bread to unsuspecting West Yorkshire wildfowl. “Tonight, Dmitri, the geese fly south to Wakefield…”

As I bring my car to a halt in a small industrial estate, there he is, waiting patiently for me amid the grumbling aftermath of a ferocious rainstorm. The mysterious artist known only as Craven Faults. Purveyor of exquisite modular synth soundtracks, suffused with the dark beauty of the oppressive moorland sprawled around us.

He shakes my hand warmly. He’s charming and chats politely as he takes me indoors, guiding me through a little network of corridors into a modest studio stuffed with ancient tape reels and battered cassettes. He’s wearing a corduroy jacket and he isn’t called Dmitri.

But I’ve probably said too much already.

Since 2017’s ‘Netherfield Works’, there’s been a trickle of long-form EPs, plus two hypnotic albums – 2020’s ‘Erratics & Unconformities’ and the newly issued ‘Standers’. All released under the Craven Faults pseudonym, and all riddled with the lonely melancholy of long-abandoned mills and mineshafts. To quote the man’s own publicity, these are “half-remembered journeys across post-industrial Yorkshire”.

So why the anonymity? Craven Faults shrugs as he carefully decants the coffee. A partial influence, he explains, was a series of now-legendary psychedelic compilations that became essential “artyfacts” in the 1970s for any self-respecting prog-head.

“I loved all that 1960s stuff, the ‘Nuggets’ and ‘Pebbles’ albums,” he says. “I picked up the ‘Pebbles’ ones in the record shop at Leeds University around 1980. They were shutting down and had 10 volumes for a quid each, so I bought the lot. There were all these bands like The Fe-Fi-Four Plus 2, and you’d think, ‘Do they exist? Or is this a joke?’. And I didn’t really want to know.

“But there was nothing deliberate with me. When I did the first EP, Tony [Morley, founder] at The Leaf Label heard it and said, ‘Let’s just keep it anonymous. We’ll put it out and see what happens’. And we’re still putting it out and seeing what happens. There was no plan. It’s almost taken on a life of its own. In some respects, it doesn’t feel much like me.”

The bleak solitude of the Yorkshire countryside, though? The psychic scars of long-defunct industry? These are clearly personal interests. At first Craven Faults seems a little reticent to agree, but then he slowly starts warming to the suggestion.

“Well, it’s instrumental music, so it’s not really about anything,” he says. “But because it’s instrumental music, your character comes into it. When I drive to the studio, I come over the hills and I can just see into the National Park. Rombalds Moor has hundreds of neolithic carved rocks. And disused quarries. And old farm buildings that have been abandoned. It’s all human intervention, and I became interested in that.”

So not just the landscape itself, but the impact of thousands of years of human behaviour upon it?

He nods.

“I like nosing about. Even when I lived in the city, I realised at an early age that there are far more interesting things to see above shop windows than through them. Or you might look down the side of a building and there’ll be an old gas lamp – there used to be one down the side of WHSmith in Leeds – and you think to yourself, ‘How the hell has that managed to stay there for 120 years?’.

“And I like the rusty bits of metal you find attached to walls. There’s one not far from here – a beautiful bit of curved ironwork. It’s just the broken end of a gate, but it’s still attached to the old post. I love that it’s still there, and there’s no need to clear it away. As a kid, I always wanted to be an archaeologist, but someone told me that you needed A-levels for it. And I only have one. In art.”

The tipping point, the moment when this gentle fascination solidified into the music of Craven Faults, began with a leisurely ramble around the tiny village of Hebden. Not, he pointedly explains, to be confused with West Yorkshire hipster hangout, Hebden Bridge. This Hebden is an altogether sleepier outpost, halfway between Grassington and Appletreewick.

“I could see a chimney in the distance,” he recalls. “The remains of Yarnbury lead mine. All the spoil heaps are grassed over now, but the ground is still rough. There used to be 5,000 people living in that valley, but now they’ve all gone. It was a town, and now it’s not. And I found that really interesting – the way urban places can become rural places.”

So is it the simple transience of human endeavour that intrigues him? Or the fact that lingering echoes will always remain, even if they’re covered in grass or just attached to old fence posts?

“I think it’s time,” he says. “I’m interested in time as a concept. My grandma was born in 1899 and she lived well into her 90s, so I knew her well. Her earliest memory was going over a humpback bridge on a horse and cart when she was two years old – that was in 1901. That’s quite a connection with a world that has changed. It fascinates me that she was born at a time when nobody had flown, and then before she was 70, there were men on the moon. Quite extraordinary.”

The artist now known as Craven Faults was born in Bradford, and lived there until the age of eight. Then, following a brief foray into Lancashire, his family settled in leafy Northamptonshire. Aged 20, he returned to his West Yorkshire roots to study art at Leeds Polytechnic, but his teenage experiences in the East Midlands had already proved transformative.

“We lived in a village,” he recalls. “And that got me into music, because there was nothing else to do. There wasn’t really any public transport, and they wouldn’t let you into the pub because everyone knew you were only 16. So I occupied myself listening to records and messing around with electric guitars. Then, in October 1976, I saw Kraftwerk in Coventry. Between me and my friend Dave, we had all their albums. I had the first two and ‘Autobahn’, Dave had ‘Ralf And Florian’ and ‘Radio-Activity’. So we were fans.”

Was it a well-attended concert, I wonder? A friend of mine saw Kraftwerk on their 1975 tour, in the cavernous main room of Middlesbrough Town Hall, and recalls the audience being sparse and somewhat bemused.

“No, it was busy,” he insists. “It was a hippy crowd. People were sitting cross-legged on the floor – they were paying attention! And I remember a massive cheer when Kraftwerk started playing ‘Autobahn’.

“Then, about two months after that, I saw the classic line-up of Tangerine Dream in Birmingham. I was 16, Virgin Records had reissued all their albums, and John Peel played ‘Fly And Collision Of Comas Sola’ on the radio, which started with that synthy sound and lots of reverb. I’d never heard of them, but I thought it was brilliant. Three days later they were in Birmingham and I got tickets at the last minute, right in the middle of the second row. It was phenomenally loud.”

And his own musical adventures?

“I was in a post-punk band from 1979.” He pauses. “This is going to give it all away, isn’t it?”

Go on, what band was it? He’s making it sound like they might even have been quite famous.

“Maybe this should be the article that tells everyone?” He pauses and breaks into a smile.

“Nah…”

Tell me, then. I promise I won’t include it in the feature.

“Give over!”

He does tell me, though. And I am true to my word, but let’s at least do the backstory. That’s allowed.

“In 1979, I was in a screen-printing room at college and there was a lad there doing some posters for the art school party,” he continues. “He said, ‘Have you got a band? Come and play’. This was on the Thursday and the gig was on the Monday. I hadn’t actually got a band, but a few of us had always talked about it, so we worked out three songs and turned up.

“We did experimental post-punk. No drummer. Just guitar, bass and a singer with an old violin. We were on for about 10 minutes and the punks absolutely hated it. We used to get so much abuse for not playing punk. But there was a guy there who ran a fanzine, and he reviewed it and loved it. So we threw ourselves in at the deep end.”

If you have an interest in the finer details of the British post-punk scene of the late 1970s, you might be aware of his first band. But you’re more likely to have heard of the band he toured America and Europe with in the late 1980s. Or, indeed, his contributions to… No. That’s going too far.

So, let’s talk about the new album instead. It’s called ‘Standers’ and it’s terrific.

“The cover is the Nine Standards Rigg – nine cairns up in Cumbria,” Craven Faults explains. “And the thing I find really interesting? There haven’t always been nine of them. Sometimes it’s been a dozen, sometimes less. And they haven’t always been in that place – they’re constantly being rebuilt.

So I like the fact it’s an ancient monument – but is it ancient? It’s like the Ship of Theseus, or George Washington’s axe. I find that funny.”

Craven Faults is fascinating, and part of the fascination is that he actively denies being fascinating. He’s gentle and genial, a modest autodidact. And the name Craven Faults itself?

“Three geological faults that run roughly east to west across the Pennines.”

The titles on the new album, as ever, reflect archaic Yorkshire dialect and the tangled etymology of local place names. ‘Odda Delf’ intrigues me, I tell him. Wasn’t she a Norse goddess?

“No, it’s a quarry,” he chuckles. “On one of the old maps it’s called Todda, but I reckon whoever made the map must have asked a local what it was called, and they said, ‘T’Odda’.”

There’s a grand tradition being followed here, isn’t there? Men in sheds humbly dabbling in harmless hobbies, amassing mind-boggling swathes of esoteric knowledge. He shows me a 19th century map of my own hometown on the National Library of Scotland website. We discuss the 1930s books of Yorkshire historians Ella Pontefract and Marie Hartley, then switch in a blink to The Pop Group and Laurie Spiegel.

And his interest in synths? Given his five-decade love of Kraftwerk and Tangerine Dream, surely he was an early adopter? Surprisingly not.

“I’m quite late to synthesisers,” he insists. “The first one I bought was a Wasp in the early 2000s.”

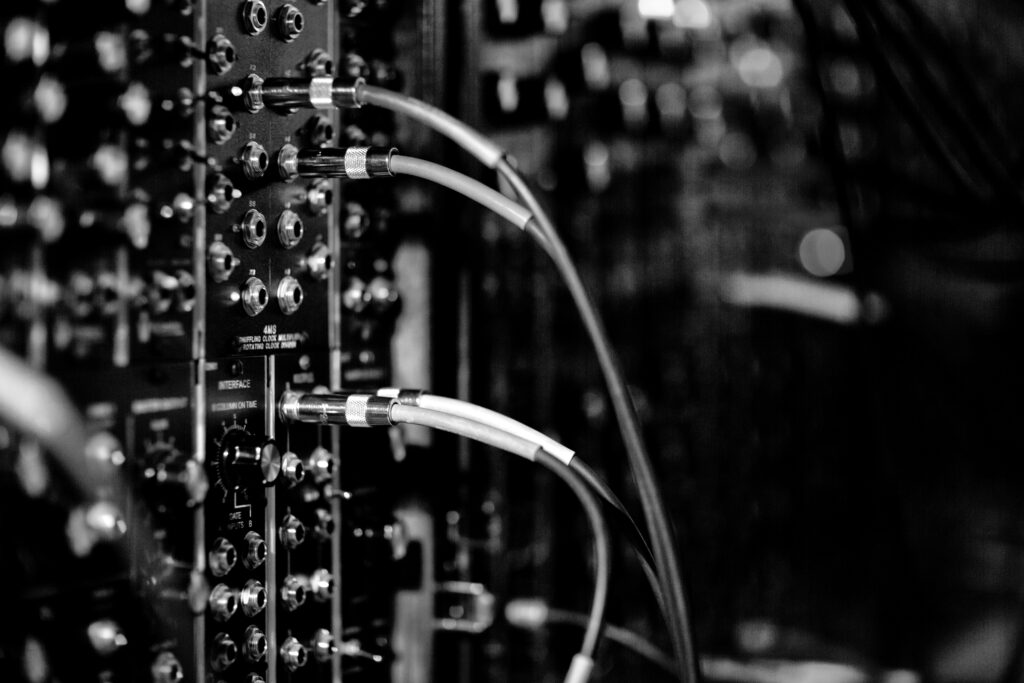

The massive modular set-up that dominates an entire wall of the studio is, he reveals, barely a decade old.

“I lived in a little back-to-back terraced house in Leeds,” he recalls. “My best friend died and we all got left some money in his will. Mine was enough to put a deposit on a house. It wasn’t a very expensive house – it had no central heating and no double glazing. And then, when I finally got some money together to do the place up, I bought this instead. So I had a massive expensive synthesiser and a freezing cold house.”

He sets off a pulsating modular loop, and I prod an aimless finger around the vintage Farfisa organ, whose unmistakable tones are weaved seamlessly throughout ‘Standers’. It’s a sound, I suggest, that links those hypnotic modular sequences with the acid-fried psych of his beloved 1960s beat groups. He agrees.

“I can make connections between Kraftwerk’s ‘Radio-Activity’ and Fleetwood Mac’s ‘The Green Manalishi (With The Two Prong Crown)’,” he says. “That one note thing – ‘dum dum dum’. I’ve always loved that. And The Beach Boys’ ‘Good Vibrations’ has got that one-note cello – ‘dum dum dum’ again. I just find it fascinating. Often, I’ll record something very clever on the synthesiser with shifts and changes. But then I’ll go back and re-record it with just a couple of notes. I prefer it that way. The more I take out of tracks, the better I like them.”

And, just to be even more contrary, it transpires that he’s actually going to be playing live this September. No, really. Four performances over one weekend at a heritage watermill on the outskirts of Leeds. They sold out in a heartbeat. Surely that’s going to blow his cover? Or is he going to venture out on stage in a mask, like British wrestling icon Kendo Nagasaki? Craven Faults chuckles at the prospect.

“I’ll be facing away from the audience, sitting at this,” he smiles, airily gesturing towards that towering, modular monolith. “And I think afterwards, it’ll just be the same. I don’t put my name on the records, and I don’t do any social media anyway. Nothing’s going to change.”

He should, I suggest, be collected by a black limousine at the watermill’s door as the last electronic pulse is still echoing around the rafters. And then what do we both say? It’s inevitable. We chant it together, in cod mid-Atlantic accents and in perfectly precise unison.

“Ladies and gentlemen, Craven Faults has left the building.”

‘Standers’ is out on The Leaf Label