Despite playing in iconic outfits Tangerine Dream and Ash Ra Tempel, it’s his solo work and the solitude of creating it that fires the electronic music pioneer Klaus Schulze. A true original, his new album is as vital today as it would have been yesterday… or tomorrow

“I never have any plans or concepts before I start a new album,” says Klaus Schulze, communicating via email from his home and studio in Germany’s Lower Saxony region. “My music is fully improvised, just expressing my personal feelings, so it is really unpredictable and wouldn’t follow any plans even if I had any! I just play and hit that record button. Music should not try to ‘educate’ people or provoke an intellectual look on things. It’s about feelings, everything is up to the listener.”

This nebulous (non)philosophy has provided the framework for the immense stream of Schulze’s work since he appeared as a drummer on Tangerine Dream’s debut album, 1970’s ‘Electronic Meditation’, along with Edgar Froese and Conrad Schnitzler.

The freedom and expansion Schulze has achieved is a result of mentally unshackling himself from rigid notions of sound creation. He even finds critical praise slightly irksome, inasmuch as it generally involves some verbal tag he refuses to recognise. Now 70, Schulze recently faced his own mortality with a bout of illness last summer, though he is currently recuperating.

“I am in fact quite well now and very happy about the opportunity to continue with my music again after all these years,” he says.

Oscillating between richly-coloured ambient swirl and impressive mega-structures made up of rigid sequencer girders, his new album, ‘Silhouettes’, is an impressive feat of musical strength and, despite feeling a touch disconnected from the modern world of electronica he helped inaugurate, it posits a notional, healthy future for the genre that is destined to outlive its creators.

Titles like ‘Der Lange Blick Zurück’ (’The Long View Back’) indicate the scale on which Schulze works and the light years he appears to have traversed. The use of the word “simplex” in ‘Quae Simplex’ gives another clue to approaching Schulze; that for all of his range, his music could be taken to be the examination of a single concept, a single planetary organism contemplated from infinite angles.

“The result may appear to be unspectacular at first sight,” offers Schulze, “but as with a microscope or a cosmic telescope, the evident should not really be what matters. Because there are levels in music that you can almost touch, that walk through the room – but first you have to allow the noise in your head to calm down so the music behind it becomes audible. Which may turn out to be very simple or very complex, depending on how far you’re prepared to venture.”

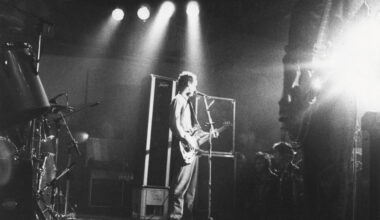

Schulze’s vision was always singular. While his krautrock contemporaries preferred to work communally, his impulse was to fly solo. He joined Ash Ra Tempel, working with Manuel Göttsching on their extraordinary proto-ambient self-titled 1971 debut album, which took flight from the tethers of blues-based rock into clouds hitherto unknown. He was also briefly a member of the unlikely supergroup Go, founded in 1977 by Stomu Yamashta, in which he played alongside Traffic’s Steve Winwood and jazz fusion guitarist Al Di Meola.

The results of that collaboration were mixed, although its better moments belong to Schulze. While he admits that he “loves a good musical co-operation and always will” he found the collaborative process a creative impediment rather than a boost.

“The reason to ultimately leave those classic band constellations was my vision; the way I wanted the music to go,” he says. “I really enjoyed my time with Tangerine Dream and Ash Ra Tempel, but I needed space to act out my ideas without compromises.”

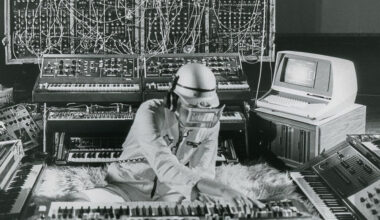

A breakthrough came for Schulze when Popul Vuh’s Florian Fricke decided to sell his synthesiser. Fricke was a man of independent means, who unlike his more impoverished experimental contemporaries had been able to buy the prohibitively expensive Moog 3P. However, he’d decided he preferred the purity of the piano and so it was, that the Moog ended up with a grateful Schulze.

“Ah, my first modular system,” he recalls. “When it came out, it was totally out of reach for me and I wanted it sooo bad. Then two unexpected factors came together – my first royalty advance from the Brain/Metronome label and the fact Florian was willing to sell his system to me. Combine those factors and you can imagine how excited I was to take the money and drive straight to Florian.”

Prior to this, Schulze had released his 1972 debut album, ‘Irrlicht’ without a synthesiser in sight. He achieved electronic sounds through primitive, musique concrète-style methods – processing drones through an electric organ, a backwards manipulated recording of a classical symphony orchestra and using filters and modifying devices to alter the sound. The effects are rather more timeless than some of his later works with more advanced technology – twisting, metallic sheet waves of grainy, luminous sound in a state of high suspension, pulsing and ebbing like a giant, hovering celestial organism.

As with Tangerine Dream’s earliest work, there is a forbidding, remote seductiveness about ‘Irrlicht’. It depicts a sound cosmos, in which the plans, aspirations, narratives and fears of humanity are a temporal irrelevance. Its sheer scale and sonic spectacle, and that of its follow-up ‘Cyborg’ (released in 1973 and this time enhanced by the EMS Synthi A), attracted the kind of audience that enabled Schulze to raise the funds to upgrade his equipment. But what were the advantages of working with a synthesiser and not the earlier ways?

“Quite simple,” he says. “Sound! I could change everything, anytime, anywhere. I could create the sounds I wanted and alter them in ways that had never been possible before. To me, the sonics mattered more than the notes or chords, so the synthesisers freed me from those boundaries. The possibilities were endless – just amazing.”

From the mid-70s, Schulze became an apologist for the synthesiser. Only with instruments like the Moog, felt Schulze, could you paint truly vivid pictures and un-moor the imagination. In this respect, it is fair to describe him as one of that select band to which the word “pioneer”, much overused in electronic music, can be applied.

“My motivation was not to be a pioneer, I just wanted to experiment and create my very own kind of music,” says Schulze. “I wanted to discover sounds and follow that fascinating path of breaking new ground. It was an adventure and while you’re on it you don’t think of yourself as a pioneer – you’re far too busy creating.”

Perhaps as a result of his prolific output (discographers have lost count of his releases, which runs into the hundreds), his association with the prog-era saw Schulze’s reputation suffer a little towards the end of the century. Yet he could feel vindicated by the eventual ubiquity of the music and instruments that he saw many studio engineers struggle to get their heads around. It was at this point that his lifetime’s achievements could be properly appreciated. It’s strange to think that there was a time when electronic music was held to be manufactured and inauthentic, but these were arguments that Schulze faced at every turn back in the 1970s.

“I think that discussion is quite outdated,” he says. “A violin was manufactured once too, and it did not grow on trees. That is how that topic was dealt with for good for me.”

It’s ironic also to think that Schulze’s vast oeuvre of technological works have been largely created in a 10-square metre space at his home deep in the forest of Lüneburg Heath, a location cited by Brian Eno on Harmonia 76’s, ‘Tracks And Traces’.

“The silence and isolation here, or let’s say my cocooning, helps me to focus on music and to be more creative,” he explains. “Don’t forget, before that I had many long years of the ‘big city life’.”

Indeed. Schulze started in Berlin, at the famous experimental Zodiak Free Arts Lab, in the late 1960s. His music was often seen as belonging to the Berlin School and it would later be foundational in the city’s techno scene – and yet Schulze is not really “of” Berlin, a place that was simply a point of the most spectacular departure.

That said, he is, in a Kraftwerkian sense, in a Stockhausian sense, “West German in origin”, though he would disavow any association with either of them. I once asked him if his music had any relationship to the political upheavals in 1968, in West Germany in particular. He replied with an emphatic, “No” and that is certainly true in the overt sense, at least.

However, what Schulze shares with West German peers as diverse as Tangerine Dream, Can and Faust, is a post-war dream of freedom – the abiding amnesia and repression of a country still not spiritually recovered from the war, a freedom to roam in uncharted mental space, a freedom achieved by the newest available musical methods and technology. It was no coincidence that they arose at the same time. The futures they constructed are the futures we inhabit, or have yet to inhabit.

‘Silhouettes’ is out on Oblivion/SPV