Welcome to the Melbourne Electronic Sound Studio, a gobsmacking collection of synths that is plugging Australia’s electronic music scene into the grid. Don’t touch that dial!

Tucked away down an unprepossessing alley in the fine city of Melbourne, Australia, is a collection of synthesisers so impressive that it makes you wonder if they’ve not switched on some kind of devilish gear magnet and gathered up every significant synth on the continent. Just reading the kit list is enough to make you dizzy. There’s a Russian Soviet-era Stylophone knock-off in there, not to mention pretty much every insect-related product the Electronic Dream Plant ever made, several iterations of the EMS VCS3, and the shocking Yamaha DX1. They only made 140 of those.

Imagine being given free reign with it all, to experiment to your heart’s content. Because that’s the idea behind the Melbourne Electronic Sound Studio, or MESS for short. It was brought into existence by local audio-visual artists Byron J Scullin and Robin Fox. One of Robin’s pieces was a giant theremin public sculpture that stood seven metres.

“What we have here is made up from several Melbourne musicians’ private collections,” says Byron. “We have two musicians in particular who have massive amounts of equipment and a penchant for vintage machines. Once we embarked on the project to create MESS, news started to spread out and we were able to make contact with these major collectors.”

You might wonder why somebody who has parted with serious dollar to build up his or her own electronic horde would be happy to hand any of it over to anyone else. But there is a very practical reason for their apparent generosity.

“The synths need to be used regularly to keep them working,” explains Byron. “If you leave old cars garaged for too long, things start to rust up or dry out, and the car will stop working. It’s less obvious, but this is also the case with electronics. Faders needs to be slid. Knobs, dials and buttons need to be twisted, turned and pressed. Corrosion can creep in and next thing you know you’ve got a volume or filter fader that’s crunchy.”

Loaning the synths to MESS means that they get fixed up, looked after and, crucially, used. MESS, then, is a bit like a high-class health spa for elderly synths, staffed by legions of devoted experts who will adore them and keep them all in the best possible condition. But it goes further than that.

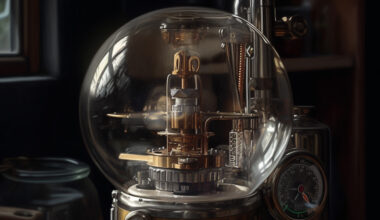

“Sometimes it’s nothing more than an owner’s pure enthusiasm for electronic sound,” says Byron. “These machines are all inspirational in their own way. Each one speaks to ideas about music, sound, design, form and function. Each embodies the personalities of the people who made them and they carry this spirit in their construction. We can trace electronic sound back to the beginning of the 20th century, but the fact is that the real boom in electronics only came after the Second World War and transistorisation.

“So electronic sound as we know it today has a history of around 75 years or so. That’s only three generations of humanity that have had access to these instruments. When we compare that to how many generations have had access to the violin or the piano, it becomes clear how new electronic sound is in terms of cultural growth. Even so, there is a growing feeling that many of these instruments are museum pieces and therefore they should be preserved.”

MESS is not a museum, however. The project’s most exciting aspect lies in its commitment to the creation of new work using the equipment.

“We feel that the machines have a ton of great new sounds and ideas just waiting to emerge, but we need to put people in front of them for this to happen,” says Byron. “This is the opposite of the museum approach. A machine that still has the potential to create sound sitting under glass or sequestered away in a personal collection is something we want to avoid. Our supporting collectors agree with us about this and they believe in the notion that we can advocate for new electronic music with these old machines.”

The MESS collection is still growing. They’ve just taken delivery of a Yamaha CS-80 and are in discussions about an ARP 2500. There’s an extensive installation of Eurorack modular pieces too. The fact that musicians will be able to access and experiment with gear that, as John Foxx has said, was junked before anyone had really explored it thoroughly is why MESS is such a great idea.

When is something like this going to happen in the UK? Watch this space…

The Melbourne Electronic Sound Studio is at 15 Dowling Place, North Melbourne, VIC 3051, Australia. For more information visit www.mess.foundation