It’s 50 years since he recorded the seminal ‘Silver Apples Of The Moon’ and a little longer since he co-founded the San Francisco Tape Music Center and helped to design the first Buchla synthesiser. So how come Morton Subotnick seems oblivious to his own musical legacy?

In 1967, exactly half a century ago, a record appeared on the seminal Nonesuch label that has, over time, demonstrated a profound influence on our sonic landscape. The composer of this groundbreaking work, American musician Morton Subotnick, described it as “chamber music of the future”, and even today ‘Silver Apples Of The Moon’ presents an uncompromising and extraordinary challenge to listeners. Comets of hissing, trilling, synthetic sound zig-zag their way across an abstract volcanic surface, as electronic pulses tumble down upon us, sirens squeal in the distance, and blipping cells spiral into concentric rings of psychedelic bliss.

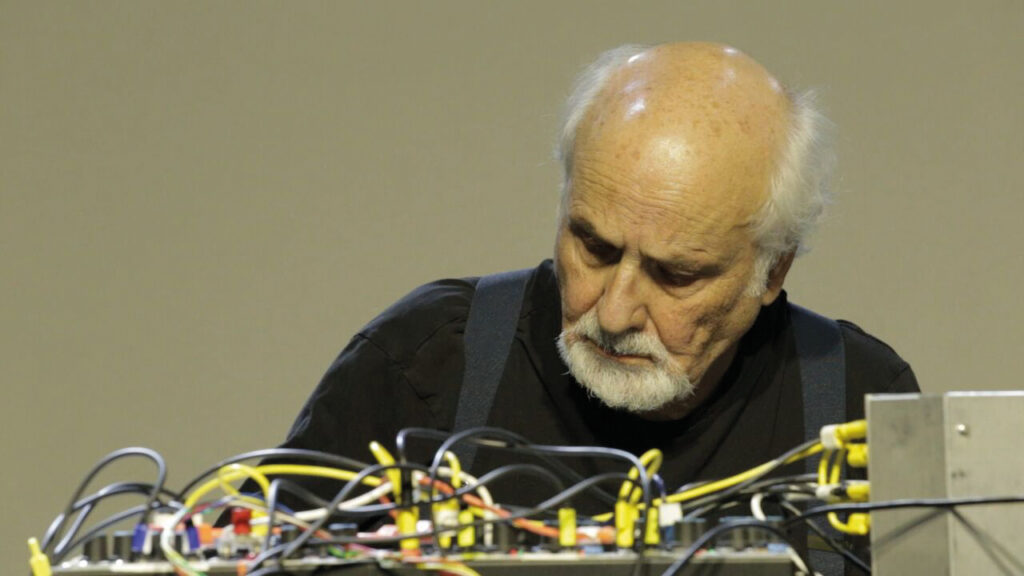

Now 84 years of age, Morton Subotnick is still very much alive and very much active, energetically travelling the globe as he presents and performs his work at theatres and festivals. In celebration of his truly pioneering vision, the makers of ‘I Dream Of Wires’, the acclaimed documentary on modular synthesisers, are focusing on Subotnick for a new official biopic. Production is under way and the film’s first theatrical screenings are scheduled to take place by the end of the year.

As Morton finished up his preparations for the premiere of ‘Crowds And Power’, a multimedia tone poem for voice, electronic sound and live imagery at the Lincoln Center in New York City in July, I was delighted to have a chance to chat with this supremely influential man, our conversation peppered with laughter at every turn.

I was interested to learn more about the San Francisco Tape Music Center that Morton established with Ramon Sender back in 1962. It was a non-profit cultural organisation – “The aim of which was to present concerts and offer a place to learn about work within the tape music medium,” according to Tape Music Center technician William Maginnis – and other electronic pioneers involved in the formative days of the project included Pauline Oliveros and Terry Riley. So how did the Center start?

“People often think of it as a public studio, and it did become that, but that’s not how it started,” says Morton. “Ramon, Pauline and I had been giving concerts at the San Francisco Conservatory and our last concert there sort of made a stir. The review the next morning said that the concert literally stank, because the dancers we performed with were using perfume. My memory was that they didn’t let us back in again! That was it.

“Pauline left for Europe and was gone for a year, but Ramon called me and said we should take our stuff and get a studio together. And that’s what we did. We went out and we found this house. At this time, I was desperate, in the sense that I had decided I wanted to reinvent my life. I was playing clarinet with the San Francisco Symphony and composing and doing all these things, but I realised that what I really wanted to do was to find a way to create an electronic music easel. I knew it was going to happen, but I couldn’t figure out how to do it.

“Ramon and I did a lot of research, picking out odds and ends, trying to do something, but it didn’t work, so we decided we should perhaps get some money. I called a woman who was giving donations to the Symphony and she said, ‘Oh sure, I’ll send you some money, but you have to become non-profit’. So I said, ‘Well, I don’t know quite what that is, but we’ll do that’. So we paid $65 to a lawyer friend to help us and we became a non-profit organisation. After that, this woman sent us a cheque for $25, which didn’t even pay for the registration!”

The next step for Morton and Ramon was to settle on a name for the project.

“The Germans didn’t allow microphones into their studios and the French didn’t allow sine tones into their studios,” notes Morton. “We were looking to do something different, so we said, ‘We’ll call it the Tape Music Center’, with the idea that anything you put on tape was music. At that time, there were no publicly accessible studios, no venues that were part of an institution, but we started giving concerts because we were still looking for finances, and one thing led to another. That’s how we became a centre and a public studio. It just grew naturally. Later on, we got a bigger place but, well, that’s a long story because that place burned down.”

I ask Morton to describe what daily life was like at the Tape Music Center in the early years.

“Well, the daily activity was based around the fact that there was no money! We survived because of my work with the Symphony and because Ramon had a stipend. In fact, I don’t think Ramon had a job until he was 65 [much laughter], but we got odd pieces of work. Most of what we got paid we ended up feeding back into the studio in order to keep it going.

“I remember once we were asked to transcribe the music on a tape sent to us by an Indian architect. He was improvising at the piano and he wanted to publish what he’d recorded, but didn’t know how to write music. At that point, Pauline had come back, so I distributed the job between the three of us, one third to me, one third to Ramon, and one third to Pauline. The funny thing was we didn’t have synchronous tape recorders, so Pauline’s pitch got higher because her machine got faster as more tape was pulling through it. So mine started in C major and hers was in C sharp [more laughter]. We wondered if we should do it again, but we decided the guy would like this and sent it to him as it was.”

The synthesiser has been a commonplace instrument for many years and even the lowest grade smartphone offers up a playground of music tools these days. But back in the early 1960s, it was still year zero in terms of the potential for electronic music. Before then, composers such as Karlheinz Stockhausen and Luc Ferrari had advanced the idea of cutting and splicing tape together. Things started to change when Robert Moog and Don Buchla began developing synthesisers at the very same time – Moog on the US East Coast and Don Buchla on the West – albeit with very different ambitions.

Morton Subotnick had a direct influence on Buchla, having commissioned him to breathe life into his idea of “an electronic music easel”. Nobody had any idea that the Buchla would eventually alter the musical landscape, having subsequently been championed by the likes of Suzanne Ciani, Trent Reznor, Aphex Twin and Amon Tobin. Nobody apart from Morton, that is.

“The first thing I told Don Buchla was that we didn’t want a keyboard, we didn’t want a new way to do old music,” he recalls. “A keyboard gives you information and I didn’t want that. I wanted to say to everyone who looked at this machine, ‘We’ve been doing the same music for over 50,000 years and suddenly we have a different paradigm now’. At the same time, it’s very hard to do something that hasn’t been done before. The best you can do is the best you can! But I felt that if you had a keyboard in front of you, it would give you information and it would end up dragging you back in time.

“As a result, it’s not like you are playing a melody, instead you are getting something you’ve not experienced before. It did take a while to get to the kind of complexity I got with ’Silver Apples Of The Moon’, though. It was 13 months of working on it for 10 hours a day. I mean, even today I can’t figure out how I did it. I knew how it worked and why it worked the way it did, so there was no learning curve to speak of, but it was only because I had some pre-experience of this stuff that allowed me to know what to do to further what I was hearing.”

Get the print magazine bundled with limited edition, exclusive vinyl releases

Morton’s music and his creative approach have sparked entire music genres, so given his remarkable activity over the years I was curious to know how he felt about the current music scene. Perhaps unsurprisingly, he’s been far too busy to pay any attention to it.

“When I made that shift in 1961, I made the decision to re-invent myself and then to live with this vision that I had. But I’m gradually reaching the point that maybe next year I can retire a little bit and see what everyone else is doing [laughter]. I guess I’ve been in a hurry to get this thing done and I never thought I’d live this long.

Ever since I was a kid, I was aware that you die, which is why I’ve always thought you’d better live the best you can. To paraphrase a quote from Jean Cocteau, ‘When I was born, death came walking towards me slowly’.

“So I’ve found myself in a world that I don’t actually know anything about. When I came back to the stage after being away for a while, there were young people with entirely different backgrounds. My stuff just didn’t sound anything like what they were doing. At first I thought, ‘What am I doing here? This doesn’t make any sense’, but then I’ve gradually become more comfortable with it. I’ve forced myself into a position where I don’t know what I’m going to do and that’s really treacherous. If you have an instrument, you can just play, but as you know the Buchla isn’t just an instrument. You can easily press the wrong button and then you’ve got a mess [more laughter].”

So how does Morton view the documentary film that is currently being made about him?

“It’s been great. It’s a little spooky, well, not when I’m doing it, when I’m being filmed for it, but it’s strange when I see parts of it, when I see myself up there on screen. Even talking about it makes my stomach a little queasy, but it’s been exciting. These guys making the film are great too. They come in and film for a whole day and I don’t even know about it. It’s incredible. I recently I spent a day-and-a-half walking through San Francisco with Ramon and we went to the house I used to live in. People came out of the house and said, ‘Oh, we heard that someone who was a composer lived here and we’ve finally got to meet you!’.

“When I turned 80, we had a party at our local private community school. A lot of people came, and everyone got up and did a little tribute, and I thought, ‘This is great! I’m at my own memorial service!’. At a memorial, people say wonderful things, but the person they’re speaking about can’t hear it. That’s what I mean about this film being a little spooky. It’s like I’m experiencing my life after I’m dead, but I’m still alive [much laughter again]. But it’s pretty exciting too, you know. Fulfilling is the word. I guess it means it’s all worked out OK.”

Indeed, it did all work out OK. Off to the bank to “stop the cheques bouncing”, as he amusingly put it, Morton Subotnick bids farewell to me. The last thing I hear is him chortling away, the founding father of electronica seemingly oblivious of his own musical legacy and yet a man much sharper and more driven than most people half his age.

For more information see subotnickfilm.com