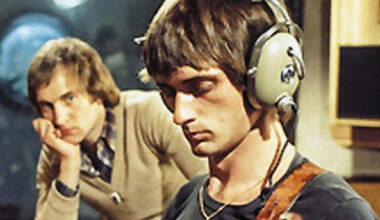

Patrick Moraz muses on days out in the 70s with Bob Moog and his synthesisers

On a spring afternoon in 1975, Swiss keyboard virtuoso Patrick Moraz found himself bounding through a field in upstate New York, carrying with him a synthesiser. Accompanying him on this unlikely outdoor jaunt, was the electronics pioneer Dr Robert A Moog.

“We used to have field trips around his laboratory in Buffalo,” explains Moraz. “And then one day, we decided to go and take some publicity pictures with the Micromoog.”

The model 2090 Micromoog was one of the latest innovations from Bob Moog and his team. The single oscillator, monophonic, monotimbral synthesiser had just debuted, with a suggested list price of $695. Adjusted for inflation, that works out to about £2,600 today, but in the 1970s the Micromoog still represented a low-cost alternative to the mighty Minimoog, which retailed for twice the price.

Patrick Moraz’s visit to New York marked the first time the two men had met and Moraz was immediately struck by Moog’s demeanour.

“I was with Yes at the time. That trip was before the second ‘Relayer’ tour, at the end of May. I stayed in Buffalo with my good friend Jean Ristori, who took the field trip picture. Bob was always very humble, extremely interested in the dialogue and the demands of the artist, and he was so open to suggestions. He was one of the few geniuses over the history of mankind.”

Moraz and Moog went on a few other photo shoots with the Micromoog, including an excursion to Niagara Falls. They wanted to go to the Canadian side “because it would make a better picture”, but were stopped by customs officials, wary of the strange device Moraz was carrying.

“We had to explain what we were doing,” Moraz says with a laugh, noting that the unit he and Moog used for the publicity shots was, in truth, a non-working model, lacking all of the internal components. “That way it was lighter to carry.”

Moraz encourages a closer look at the photo taken by Jean Ristori.

“I don’t know if you’ve noticed,” he says, “but Bob had a kind of cable that he’s holding, like I would be on a leash with the Micromoog! He wanted to make sure people understood that I was so attached to his instrument, whether it was the Micromoog, the Minimoog or – in the very, very near future – the Polymoog.”

While in Buffalo, Moraz also spent a good amount of time at Moog’s lab and workshop.

“I was astonished at how a little place like that could create such wonderful instruments, at how diverse all the pieces were, and how Bob’s assistants assembled them,” he says. “It was almost like a finely-tuned garage, but with all kinds of parts that I had never really seen before. It was an amazing, amazing journey. He introduced me to his fellow workers. He showed me so many things, and I was absolutely convinced, especially with the Polymoog!”

The Polymoog represented another great leap forward from the mind of Moog. Up to that point, analogue synthesisers were limited, at least in one sense. Musicians could only play one note at a time. In practical terms, that helped explain why synth players like Rick Wakeman – Moraz’s predecessor in Yes – had so many keyboards onstage. But the Polymoog was a fully polyphonic instrument that also featured a bank of preset sounds.

Moraz went on to explore the capabilities of the Polymoog on his 1976 debut solo album, ‘The Story Of I’, and Bob Moog would be a key figure in the creation of that record. Work on ‘The Story Of I’ began in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, where Moraz assembled a group of 16 percussionists.

“In three days in Rio, I recorded the percussion tracks for ‘The Story Of I’,” says Moraz, still beaming with pride at the resulting recordings.

Returning home to Switzerland, he aimed to continue work on the album. But he enlisted some help.

“I was able to invite Bob Moog and his first wife, Shirleigh, to Geneva for three weeks, and he helped me with the Polymoog during the recording. I composed most of the music on the spot there. I remember that for the opening sequence called ‘Impact’, I was explaining to Bob what I was hearing as sounds in my head. I had tested the Polymoog in Buffalo earlier on, but I didn’t know exactly how to use it in its best capacity.

“The curtain in the jungle opening and the rawwwr – he helped me create the possibility of doing those sounds. I was explaining how I would like these electronic movements and their frequencies, and Bob was able to help me with those. We had an extraordinary feeling of sonic empathy. Bob Moog was so unbelievably calm as well. We could really, really communicate together at the highest order of information transfer.”

Even though ‘The Story Of I’ is nominally a solo album, Moraz gives massive credit to Moog.

“Of course, Bob did not play any of the instruments,” he says. “And even if he didn’t stay for the four months it took to record it, the spirit of Bob Moog’s vision absolutely reigns over the whole work. He was always very creative, and he was always also open to the merging of the spirits. Bob’s legacy is universal.”

But it’s down-to-earth as well, a fact underscored by that photo of the field trip with his new friend.