Arty new wave outsiders who became unlikely pop stars, The Associates shook the 80s firmly by its lacy lapels. Three decades on, bandmates Alan Rankine and Michael Dempsey try to make some sense of it all…

Billy MacKenzie and Alan Rankine met on the Scottish cabaret circuit in 1976, forming an instant bond that would span two decades of hits and splits, break-ups and breakdowns. It was a rare, potent, combustible chemistry that made The Associates one of the most glamorously strange British bands of the 1980s.

Blessed with a unique voice of volcanic power and multi-octave range, Dundee-born Billy MacKenzie was a hugely charismatic frontman. The eldest of six children from a working class family with Irish traveller heritage, he was diabolically charming, elusive, bisexual, given to myth-making about his colourful life, but easily bored and prey to mercurial mood swings. Raised in Linlithgow near Edinburgh, Alan Rankine was younger and provided a stable anchor for his friend’s flighty temperament. A gifted multi-instrumentalist, he combined darkly brooding good looks with the quick-witted skills to translate MacKenzie’s audacious ideas into magnificent music.

“They were a very unusual partnership, but they bounced off each other brilliantly,” recalls Michael Dempsey, who left The Cure to play bass for MacKenzie and Rankine after The Associates signed to the London-based Fiction label in 1979. “I’d never heard anything like it. I’d come from The Cure, which was a completely different world. The Associates didn’t really sound like anything else to me then… and they still don’t now.”

Drawing their electrifying energy from Roxy and Bowie, Sparks and Moroder, Billie Holiday and Diana Ross, funk and soul and disco, The Associates created maximalist mini-operas of emotionally charged, densely layered, high-gloss melodrama. MacKenzie’s self-styled “screeching hysterics” delivery suggested euphoric release, but always with a hint of mania behind his twinkle-eyed, heavily dimpled smile.

“I think it must have been quite tortuous to be him,” Rankine says of his late musical comrade. “Singers and frontmen, that’s a hell of a lot of pressure. Bill couldn’t turn off the creativity within him. I think sometimes he just wanted someone to open up the back of his head and take out his brains, like blankets that had been in the spin dryer, then fold them neatly and put them back.”

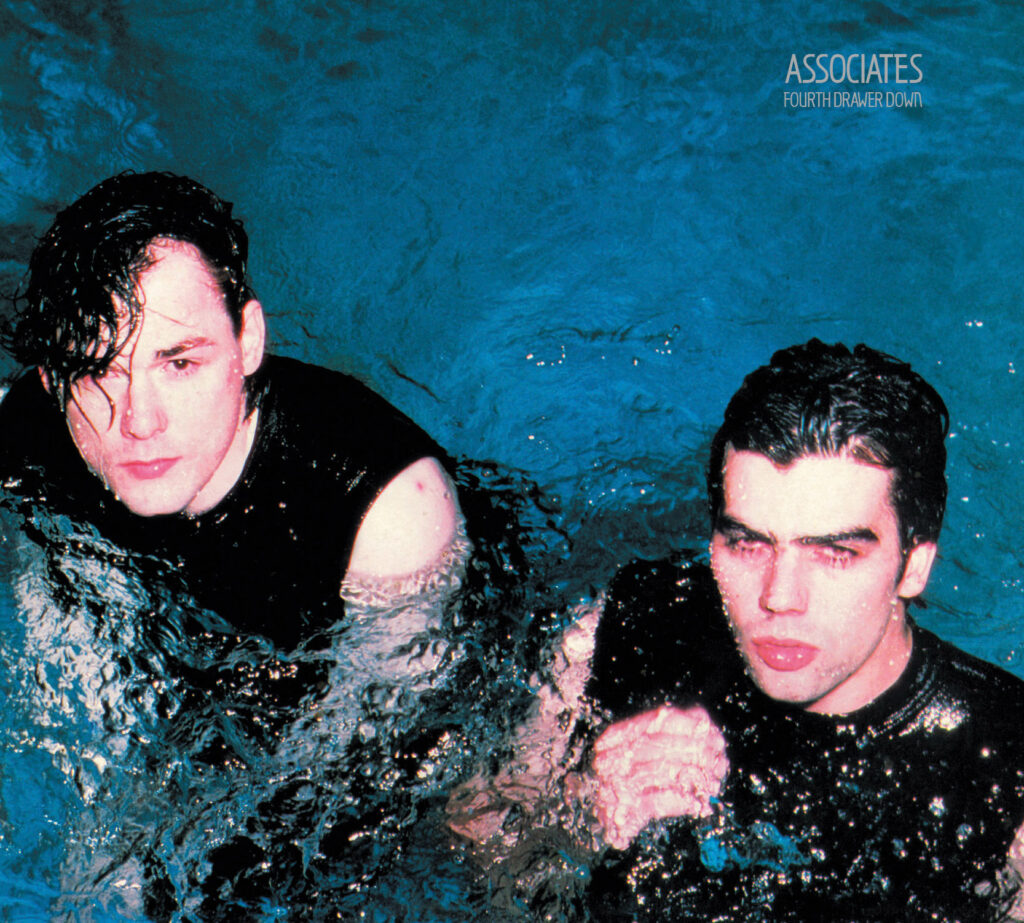

After a brief but incandescent imperial phase, the classic Associates line-up was over by 1982. Now their first three albums from this blazing first act – ‘The Affectionate Punch’, ‘Fourth Drawer Down’ and ‘Sulk’ – are being repackaged in expanded double CD and vinyl editions. Charged with overseeing the project, Michael Dempsey spent nine months tracking down more than 600 tapes in various studios and vaults. He also handled negotiations with the lawyer appointed by Billy MacKenzie’s family to look after his estate.

“Everything about their existence was chaotic, so the placement of master tapes was equally chaotic,” says Dempsey. “They were all over the place. They were stuck in record company cupboards, basements, studios. Warners had some, Universal had some, I had some which I’d kept my hands on. We haven’t got everything, though. I’m very often asked for the multi-track masters for ‘Club Country’ and ‘Party Fears Two’, which long ago disappeared. Nobody really knows what happened to a lot of the tapes. There are stories that Billy found a home for them at the bottom of the River Tay. That was the story of ‘The Glamour Chase’, one of his later albums.”

Among the half a dozen previously unheard tracks scattered across the reissues are a ragged cover of the vintage Paul & Barry Ryan hit ‘Eloise’, a couple of shelved collaborations with future Stone Roses and Radiohead producer John Leckie recorded at Abbey Road Studios, and a handful of scrappy sketches from the duo’s early years in punk-era Edinburgh.

“Some of these tracks I haven’t heard for 35 years,” laughs Alan Rankine. “There’s a song called ‘Jukebox Bucharest’… that’s going back 38 years! It’s too fast for its own good. My guitar sounds like a wasp that’s about to die, it’s so tinny and massively compressed. There’s nothing that makes me cringe, but the naivety in some of the performances and some of the lyrics… You think, ‘Eeee!’, but it does kind of fit in with the punk ethos.”

MacKenzie and Rankine were equally punk in their embrace of analogue electronics. If their early recordings sound wonky, warped and slightly otherworldly now, that’s because they treated technology as a toy to be creatively abused and studios as experimental sound laboratories. Rankine recalls using a Fairlight synthesiser and early Roland drum machines, but also finding alternative percussion sources, like an electric typewriter with its carriage return lever stuck on shuddering repeat.

“The mixing of analogue and digital definitely made things sound a little out of sync with each other,” he nods. “I really can’t think of one song where anything was sequenced.”

“You weren’t going to get those two to read the manual or learn how to programme a drum machine,” laughs Dempsey. “There was probably one guy in London at that time who knew how to programme a TR-808, but we didn’t have the money to pay him so we just pressed play. That was nearest The Associates got to electronics for me.”

The crown jewel among the reissues is ‘Sulk’, the sumptuous 1982 album that transformed The Associates from cult-ish outsiders to bona fide major label pop stars. It was recorded at Playground Studio in Camden, the band blowing most of their £60,000 advance from WEA Records on block-booked sessions and a lengthy stay at the nearby Holiday Inn, where they racked up huge weekly bills. MacKenzie’s beloved pet whippets had their own room, dining on expensive smoked salmon delivered to their door. Vast amounts were also spent on cashmere jumpers, taxis and unorthodox sonic experiments, such as dunking drum kits under water and urinating in guitars.

During the album’s all-night recording sessions, the group became notorious for a reportedly prodigious cocaine consumption, a reputation that both Rankine and Dempsey insist has been greatly exaggerated.

“We were probably doing about two grams of cocaine between seven people in the studio in a whole day,” Rankine protests. “We were actually complete lightweights! Other bands were much more excessive.”

In fact, their provincial innocence about drugs almost proved fatal.

“We were so green,” continues Rankine. “One night in the studio, we couldn’t get any coke, so we got seven grams of amphetamine sulphate. We didn’t know the difference! So after two or three days in the hospital on heart monitors, balls up inside our bodies, cocks the size of fucking chestnuts… We learned our lesson with that.”

‘Sulk’ became a Top 10 album in May 1982, spawning two all-time classic singles, ‘Party Fears Two’ and ‘Club Country’, which the band promoted with some memorably mischievous ‘Top Of The Pops’ appearances. Against the odds, The Associates had gatecrashed the palace of pop.

“We just didn’t fit,” says Rankine. “We weren’t new romantics. We didn’t obey any rules. We were a bit barking mad. But you just go along for the ride. Once that machine kicks into play, you’ve really just got to go with it.”

“They weren’t trying to please anybody at all,” says Dempsey. “The Associates never fitted in, they were always on the outside, but not so far on the outside as to be unlistenable. It’s not easy in places, but if you persist it is interesting. There was also an indie chart at the time and their early stuff did belong in that world. But they had expensive habits, they liked to stay in nice hotels, so pop exposure was a necessary part of the equation. I don’t really think that’s where they would have stayed forever, though.”

And so it proved. Inevitably, the obligations that come with major label success soon became too restrictive for a volatile free spirit like MacKenzie. Never at ease on stage, the singer cancelled a promotional tour for ‘Sulk’ at late notice, scuppering a $600,000 deal with Seymour Stein’s fabled US label Sire in the process. Rankine quit the band in frustration, his friendship with MacKenzie in tatters.

“You could sense it,” recalls Rankine. “With a world tour coming up, Bill just said, ‘There’s no way I’m fucking doing this…’. But I don’t hold that against him in any way. Not now. I know he didn’t feel comfortable. I think he just wanted to create, he didn’t want to do what was required of him. He felt that was stagnation.”

“Billy had sort of tipped me off that this wasn’t going to go much further,” says Dempsey, who left the band soon after Rankine. “I don’t think even he knew how he was going to dismantle it, but he did it in pretty dramatic style, waiting until the night before a gig up in Scotland to announce he wasn’t going to do it. Prior to that, they had met up with Seymour Stein and been offered a very substantial deal, but Billy didn’t want to do it. I think Alan knew this was going to be a struggle. Billy was such a forceful character, you couldn’t make him do anything.”

Rankine admits he initially felt anger towards MacKenzie for sabotaging The Associates, but only for a few weeks. He now accepts the singer’s reasons for aborting the tour were valid, since the task of reproducing their lush studio sound onstage was becoming increasingly laborious.

“It was too unwieldy,” nods Rankine. “In the summer and autumn of 1980, we had been a lean four-piece: guitar, bass, drums and Bill. Then suddenly, two years later, we were a nine-piece with two keyboard players, a female back-up vocal, a male back-up vocal… and it was all wrong. It didn’t feel right to me either, but I thought we would be able to iron out the problems. We should have just stripped it back again. Whether we would have got away with that on a world stage, I don’t know, but you’ve got to keep on moving things along.”

The Associates’ name endured for another eight years, essentially as a vehicle for MacKenzie’s erratic output, but he never regained the commercial heights of ‘Sulk’. Both MacKenzie and Rankine worked separately on a number of collaborations and solo albums, briefly reuniting to write songs together again in 1993. But as before, the singer’s allergy to record companies and touring soon stifled any comeback potential.

In January 1997, Billy MacKenzie killed himself by taking an overdose of prescription drugs and paracetamol at his father’s house near Dundee. Depression over his mother’s recent death was a major factor. He was 39. His former band members were deeply shocked.

“I never saw him tortured,” says Michael Dempsey. “He was one of those people who was always upbeat and always ready to move on to the next thing.”

A glorious musical fireworks display that ended in tragedy, The Associates’ story now feels like an unfinished symphony. Their premature demise left a big question mark hanging. If MacKenzie had bitten the bullet, signed to Sire and toured America, maybe these self-destructive outsiders would be arena-filling alt-rock veterans today.

“That’s a very big ‘What if?’,” frowns Dempsey. “Billy was never really a comfortable live performer and he wasn’t someone who liked structure in the slightest. He just wasn’t built for touring. Alan was different, he was prepared to do it and he would have enjoyed it as well. But if your singer isn’t prepared to do that, it’s not going to happen.”

Alan Rankine has spent more than three decades pondering what might have been if MacKenzie had been more disciplined and career-minded.

“You can’t dwell on the past, there’s no point… but of course I do,” he smiles. “I still think it would have come apart at the seams at some stage. In time, the wheels would have come off the wagon, without a doubt.”

Despite their relatively brief time in the limelight, The Associates left a rich musical legacy. They remain beloved by friends and contemporaries such as Bono, Morrissey, Siouxsie Sioux, The Cure and Heaven 17, while many younger artists cite Billy MacKenzie’s spine-tingling vocal acrobatics as an inspiration. But something so rich, strange and beautiful could never have lasted.

“They were quite unmanageable, in virtually every respect,” says Dempsey. “They were so headstrong, they wanted to do what they wanted to do, they didn’t think in terms of commercial decisions or having a career in music. It’s a great story of a short-lived success, but a very bright star when it did burn.”

The deluxe editions of ‘The Affectionate Punch’, ‘Fourth Drawer Down’ and ‘Sulk’ are out on BMG