The development of new sound technology like Sony’s 360 Reality Audio is changing and redefining our sonic experience. Welcome to the world of Immersive Listening

An offhand comment by Tony Visconti sparks the initial idea. I’m talking Marc Bolan with him, close to the end of a charity re-recording of ‘Get It On’ at the historic RAK Studios in west London. The chat in the mixing room turns to other projects that Visconti is working on, including his remastering of ‘The Man Who Sold The World’, David Bowie’s third studio album, which was originally released in November 1970. Visconti, who produced the classic album first time round, is raving about Sony’s 360 Reality Audio technology, which he has at his disposal.

“It really does sound amazing,” he glows. “It’s like David is in front of you and the band is behind you.”

It’s a phenomenon I’ve encountered myself fairly recently, during a demonstration of the stunning virtual reality video promo for Haiku Salut’s single ‘Occupy’ after one of their London shows. With the headset on, I jumped from being in the audience to standing alongside the trio as they performed, with all manner of otherworldly presences flying around me.

“We collaborated with Aaron Bradbury and Robin Newman to create a virtual world where you can live inside the music,” explains Haiku Salut’s Sophie Barkerwood. “You put the headset on and find yourself in this black space with the three members of the band playing the song around you. The idea of putting the audience at the centre of our set-up was to give people a perspective of our show that no one usually gets to see because they’re facing the stage.

“Look left and there’s a ghostly Gemma playing the sampler right next to you. Turn about and there’s a ghostly Louise on the synth. She’s almost breathing down your neck and being so close to everything is quite an unsettling experience at first. We wanted to achieve a sense of intimacy and connectedness, but the fact that everything around you seems so real, yet you reach out and can’t touch any of it, makes you feel very distant from the world. It’s a strange juxtaposition, familiar and alien at the same time.”

The conjuring up of spectral figures goes back to Haiku Salut’s famed lamp show, which sees them using more than 30 charity shop lamps of different sizes and designs, all wired up to their equipment and programmed to flicker to the music. One of the band’s tours featured stand-alone picture frames and windows within which shadowy characters would appear and disappear in a set designed as a haunted living room.

“The images were created using volumetric filmmaking, which is a technique that captures a three-dimensional space,” explains Sophie. “In this instance, they were a 3D element that moved around within the frames and sometimes seemingly out of them and onto the stage.”

So why is the idea of immersive technology becoming increasingly popular?

“Examining feelings and finding new ways to present them is exciting,” says Sophie. “It’s emotional and technological exploration. Art is often about connections and there are increasingly more and more ways of constructing threads between people. I think this works particularly well with virtual reality because, when you’re in it, you’re not expecting to be interrupted by anything else – people, thoughts, notifications. It maintains some sort of link to physicality and experience without disruption. You have no choice but to be fully present in it and surrender to it.”

From the days of Pink Floyd’s early psychedelic light shows to the dazzling extravaganzas of the rave era, the idea of matching music with intense graphics is nothing new. What has changed in recent years, however, is the desire to reshape the sonic experience to become every bit as mind-blowing and unexpected as the visual one.

It’s a movement that is evidenced throughout the artistic spectrum. Turner Prize-winning artist Mark Leckey – a man who once said his single biggest inspiration was the hardcore rave track ‘Trip II The Moon’ by Acen – used strategically placed speakers in a darkened room in his recent show ‘O’ Magic Power Of Bleakness’ at Tate Britain to enhance his grainy VHS projections, evoking the myths and memories of childhood and adolescence. In the same way, the launch of the Amazon Echo speaker caused a flurry of excitement as it brought spatial sound to the nation’s living rooms via a single box, completely bypassing the need for meticulously arranged multi-unit set-ups.

The revolution is set to continue expanding according to Junkerry, the French multi-disciplinary artist. Junkerry uses spatial sound and a mixture of visuals and sensory deprivation in her ‘Amaurosis’ show, which she staged at planetaria in Bristol, Birmingham and Plymouth last year. Her eight-speaker rig enables her to choreograph the audio using some rather special sonic trickery developed in conjunction with King’s College in London to give it a physical trajectory.

“Until now, it’s been left to the specialists,” she says. “It’s been very complicated, but now we’re starting to see some really cool tools for the composer to be able to bring that kind of performance to any place.”

Junkerry points to developments such as Max software, which is used to pan and throw sound, being bought by and incorporated into Ableton Live, as a sign that a full-on democratisation is just round the corner. Similar to the adaptations in VR, which she has also utilised in a show at London’s V&A Museum, she thinks that the novelty factor will soon give way to the use of sonic technology to generate different forms of music.

“We’re on the verge of an age when the tech will make the epoch, instead of it just being gimmicky marketing,” she insists. “I think people will harness these advances to create a fresh genre in itself. We’re really seeing a revolution that will enable the new generation to access this technology and help it reach a much larger audience.”

But despite the undeniably high-spec equipment involved in staging ‘Amaurosis’, another much more basic device is also central to its success. Junkerry’s performances feature impressionistic graphics by the artist Lucy Hardcastle, but for the first 10 minutes of the show the audience are blindfolded. Why is that?

“I wanted to remove all distractions, because we live in such an overwhelmingly visual world,” she explains. “The performance is about the art of listening and you can never have a room dark enough because you have to have things like emergency exit signs.”

Innovating with old techniques as well as the most up-to-date knowledge is something that also appeals to the legendary producer Youth. He readily admits to having a fascination for new sound technology – “I’m a producer, of course I love gimmicks!” – but he’s suspicious about how far tech alone can push boundaries.

“At the end of the day, we only have two ears to hear with,” he notes sagely.

As someone interested in the nuts and bolts of music production, Youth adds that he has always been intrigued by The Beatles’ rudimentary experiments in stereo, which was an emerging technology at the end of the 1960s.

“All the drums were on the left, all coming out of one speaker,” he says. “George Martin didn’t think it would take off, so they left it to a tape-op to run off the stereo mixes.”

Five or six years ago, Youth found himself working on some mixes in 360 Reality Audio with The Jam’s former engineer Mike Brady. He’d been impressed by the demonstration recordings, one of which was a box of matches being shaken around the listener’s head, so he tried mixing a few tracks by The Who in the format. He wasn’t enamoured with the results – “I gave up in the end because they seemed a bit odd” – but he’s excited by the advances in more conventional live music tech, such as the move to six-stack systems to combat sound delay at bigger shows and the curved speakers that help target sound for maximum efficiency and clarity.

“I did a Killing Joke tour in the States last year with Tool,” he says. “Tool were mixed in stereo front-of-house, but they had speakers at the back of the hall and above the audience. Most of the sound was coming out of the front-of-house speakers, but their engineer used a joystick to throw elements to the other speakers in bits of the show, like the drum solo, which they panned all around the room.”

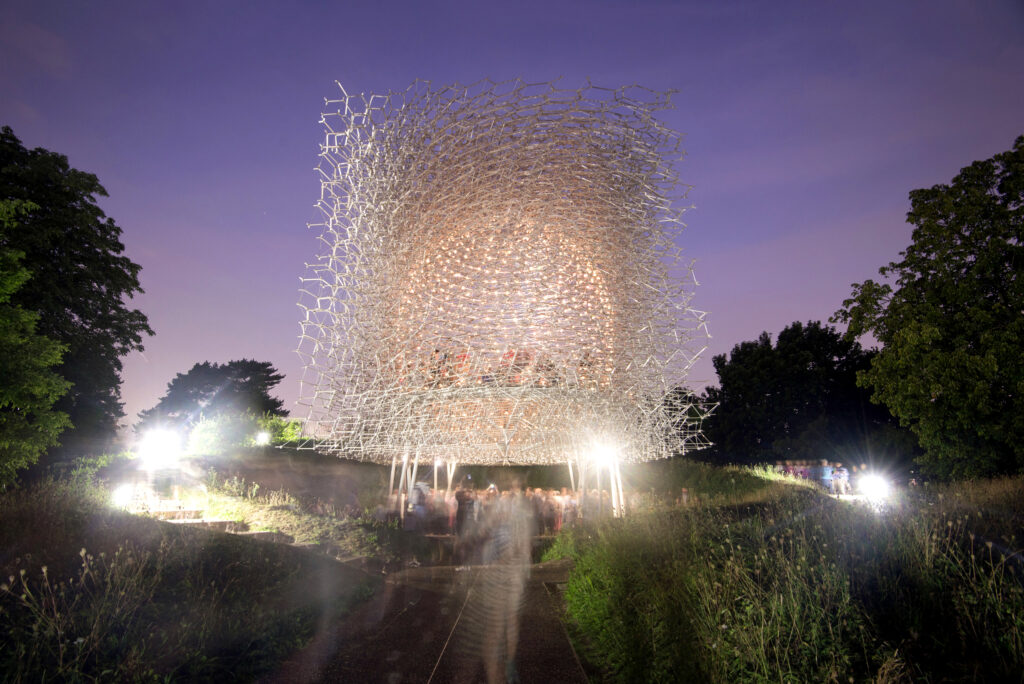

Youth thinks the most dramatic use of binaural sound he’s encountered recently was at The Hive, an art installation in Kew Gardens by Wolfgang Buttress. It’s a huge structure, incorporating thousands of LED lights, with the music triggered live by the activity of bees in real hives positioned elsewhere in the gardens. The audio library was created when musicians improvised to a live feed of a beehive. Bees apparently tend to coalesce around the key of C.

“The real cutting-edge stuff with this is happening in the art world,” says Youth. “It’s understandable that artists are trying to create a more immersive experience. As a mixer myself, I’m trying to achieve that on a stereo mix – something you can really dissolve yourself into.”

In other words, technology will push the possibilities, but it’s no replacement for creativity. The way that we listen to music continues to change and always will do, but it will be interesting to see what effect the prolonged self-isolation necessitated by the Covid-19 outbreak might have on such trends. It may be that a world in which everything revolves round you, as the immersive listening experience attempts to replicate, becomes part of the new normal. On the other hand, once we are finally released from our collective bondage, we may reject that level of immersion as being far too reminiscent of this troubling and traumatic period. Time will tell.