They pooled their gear to record their first singles, which they then released on their own labels. Thomas Leer and Robert Rental, old friends from the town of port Glasgow on the Clyde, were the original bedroom producers and key players in the nascent diy electronic scene of the late 1970s. And they didn’t own a single synth between them

“To be perfectly honest, I wasn’t too keen on the idea to start with… I mean, it’s a little embarrassing to have an exhibition about you and your mate,” says Thomas Leer about ‘From The Port To The Bridge’, which runs until 28 October at Greenock’s Beacon Arts Centre. The show serves to highlight the contribution of two all-too-often overlooked pioneers of DIY recording, Leer and his close friend Robert Rental. Both were active at a point in the late 1970s when punk’s libertarianism allowed musicians such as Leer and non-musicians like Rental to free themselves from the shackles of industry convention and expectation.

Accompanied by live performances from a range of artists, ‘From The Port To The Bridge’ includes old kit used by Leer and Rental, archive newspaper articles, reviews, photographs and selections of Leer’s later solo work, plus material made with Claudia Brücken in Act. The exhibition has been painstakingly organised by archivist Simon Dell, with support from Rental’s family and Leer himself.

“Simon’s collected up a lot of Robert’s old gear that was hanging about,” says Leer. “I’ve had so many bits of equipment over the years. I think I’ve gone through everything in the four decades I’ve been doing this, so I didn’t tend to hang on to effects pedals and stuff. But I did hand over the bits and pieces that I’ve still got, some sequencers and what have you.”

Greenock is one town along the River Clyde from where Leer was born and is where he currently calls home. He admits to being a little mystified as to why the exhibition is happening in his home town of all places, among his neighbours and within his local community.

“None of this stuff happened here,” he says, bemused. “Robert and I left this area to go away. Our careers started in London, and that’s where we did everything. I only came back here for family reasons, because my parents were ill. If it hadn’t been for that I’d have stayed in London. I was very happy there.”

Robert Donnachie and Thomas Wishart, as they were originally known, were born in 1952 and 1953 respectively in Port Glasgow, just upriver from Greenock. Originally a small fishing hamlet, Port Glasgow became important because of a geographical coincidence – it limited the burgeoning transportation of trade along the Clyde to Glasgow in the 15th century. A series of sandbanks further to the west meant that large ships could not find safe passage into the city itself, and thus a thriving harbour and shipbuilding industry developed.

As with elsewhere in Scotland, shipbuilding was already waning when Thomas Leer and Rental Rental finished their education.

“Robert was a year above me, so I never saw that much of him in school,” says Leer. “I did know of him though, and I’d seen him around town. He used to come to gigs my band played at halls, but apart from that I didn’t really know him. We met properly when I left school, at my first job. I was a gardener’s apprentice and he was the other apprentice. We spent hours standing in a potting shed talking about the John Peel show and music we discovered that we both liked.”

Inevitably, as is often the case, talking about music turns into wanting to make it…

“Robert was really keen to be a musician, but he couldn’t play at all,” says Leer. “So for a good few years, we just hung about together. I got him a gig as a roadie for one of my bands for a while. I think he bought himself a guitar and tried to learn how to play, but he really couldn’t work out how.”

In 1971, Leer and Rental headed to London.

“We decided to form a commune with a bunch of hippies,” says Leer. “I think we had a place up in Hammersmith, and then we had a squat after that somewhere else. There were always loads of groups playing free shows somewhere in London, folk like Hawkwind and all these old hippy bands, and eventually we thought we should put a band together too. That was when Robert and I started playing together. We weren’t trying to get into the music business. It was purely a subculture thing.”

Their nascent group didn’t really go anywhere, and Leer and Rental found themselves back in Scotland, this time settling in Edinburgh. |No sooner had they arrived, than the punk movement started in earnest back in London. It wasn’t long before the pair, plus old pal Andy Aitken and Leer’s girlfriend Liz Farrow, headed back down south and formed a new group, which they called Pressure. They performed a few gigs in London but never got as far as recording anything.

“By that point, Robert had become quite good on guitar,” says Leer. “But it was punk guitar and we only needed to know a couple of chords, so none of us had to be great musicians. But that was really the beginning of Robert starting to experiment with music. When we went on to synthesisers, he had to try and play keyboards, but the music we were playing again didn’t require great keyboard skills. It was mostly about the sound.”

Punk’s guiding light burned brightly for the briefest of periods around 1977, before rapidly going dim, and Pressure’s fortunes were no different.

“I became bored with punk music,” says Leer. “I just wanted to do something more interesting than thrashing out two-chord songs. Robert and I had always been really into the German thing, Kraftwerk and Can and all that, so that was what I wanted to do from that point on. I wanted to bring that electronic element in. It split the band up… and that’s when I decided to make my first record.”

Thomas Leer recorded his first single, ‘Private Plane’, in his London flat in 1978. There was no producer at the sessions and no record company to release or promote the single. Come to that, Leer had virtually no equipment with which to record the two songs: it was just a guitar, a bass, a Roland organ drum machine, a Watkins Copicat tape loop echo unit, a bunch of effects pedals, and a borrowed four-track Tascam tape recorder.

A few London streets away, Robert Rental was also accumulating kit. Just like in their hippy commune days, they pooled the modicum of equipment they had together.

‘Private Plane’ is perhaps exactly how you might expect something to sound by a musician influenced by both punk and German music: the primitive drum machine and unswerving bassline give the song a modish motorik pulse, while manipulated found sound interventions and white noise add an unpredictable dynamic. At the centre is Leer’s warm, tender vocal, full of wide-eyed wonder with a delicate Scottish lilt. The wiry guitar of the B-side, ‘International’, nods more obviously to the music of 1977, being an altogether rawer proposition, but one that hardcore punk hangers-on would find hard to embrace.

Almost as soon as Leer had finished recording these two songs, he took the kit to where Rental was staying nearby and started recording what would become Rental’s own self-released single, ‘Paralysis’, which Leer is credited as producing.

“I guess I was kind of the producer,” he says after a pause. “I did my sessions alone in my own place. Robert didn’t know how to use the gear, whereas I was already pretty well versed in it, so I stuck with him for the ‘Paralysis’ sessions, set it all up, got the sound, and then he laid the tracks down.”

‘Paralysis’ was notable for deploying a Stylophone alongside the rest of the pair’s assembled equipment.

“It wasn’t the little Rolf Harris one,” says Leer. “It was a big one. It had two styluses and a wah-wah pedal, so it was a pretty elaborate kind of Stylophone.”

That was as close as either ‘Private Plane’ or ‘Paralysis’ got to using a synthesiser. If you listen carefully, you can just about detect an umbilical linkage thanks to the shared kit, but it is slight; Leer’s work is softer, more polished, whereas Rental’s is harsher and more obtuse. Both singles felt like strict one-offs, flashes of brilliance that would set them up to be curiosities of the era.

“When we made those records, Robert and I were planning to put an electronic band together,” says Leer. “We just saw them as kind of introductory things, just chances to make a record. We weren’t vying for a career or anything like that. In those times, people just got on and did things.”

Until their singles were released, neither Leer nor Rental were aware that they were following similar paths to other genre-defining artists of the era, whose momentum had also been fuelled by punk.

“When the records went out, we discovered there were all these other people who had also been doing the same thing – people like Daniel Miller, The Human League, Throbbing Gristle, Cabaret Voltaire and The Desperate Bicycles,” says Leer. “We didn’t know anything about them. It wasn’t a scene, it was more a cultural thing that sprang out of the punk movement – we didn’t have to go to record companies and get record contracts. We didn’t even have to go to an independent record company. We could just do it all ourselves.”

Despite actively trying to avoid record labels, Leer and Rental both found tracks from their respective singles appearing on Cherry Red’s important ‘Business Unusual’ compilation in 1978, alongside tracks from Throbbing Gristle, Cabaret Voltaire and UK Subs. Leer ended up signing with Cherry Red and staying with them from 1981 to 1985.

“It was just circumstance,” he says. “They sent us a cheque for being on that compilation, and when I phoned them back to thank them, they asked me if I wanted to sign with them. And I just said, ‘Oh, OK, why not?’”

Separately, Rental had struck up a friendship with Mute man Daniel Miller, who had released his own self-produced ‘Warm Leatherette’ single as The Normal. An opportunity came up for The Normal to support Throbbing Gristle at a one-off gig, as well as joining trad punks Stiff Little Fingers on their 1979 UK tour. Rental joined Miller for those shows with an angsty, semi-improvised set effectively consisting of one long, sprawling mess of a track. Their 30-minute slot baffled the Stiff Little Fingers audiences and, on the recorded evidence from their March 1979 show at West Runton Pavilion in the wilds of Norfolk, which was released as a single-sided LP in 1980 by Rough Trade, it’s easy to see why. As a piece of abrasive sonic art, it was perfectly placed within the cultural movement that had arisen out of punk’s ashes, but it jarred with those who were still flying the punk flag.

According to Leer, Miller’s original intention had been to ask both himself and Rental to join him on stage.

“There was some kind of a foul-up,” says Leer. “I think Daniel approached Robert through Rough Trade and, from what I heard, he was asking for the two of us to work with him. I don’t know if that’s true or not – that’s just what I’d heard; maybe he only ever wanted to work with Robert. The last thing I wanted to do at that time was a live performance. If it had been making a record together, I’d have been right in there. I’d have loved to have worked with Daniel, but I just didn’t want to do live stuff at that time. I was too keen on getting into the studio, but I did actually go to some shows and help mix the sound for them.”

Later in 1979, Leer and Rental recorded their one and only album together, ‘The Bridge’, which was released by Throbbing Gristle’s Industrial label.

“We used to go to their gigs, and we’d talk to them after shows, so we kind of got to know them,” says Leer.

“The chance to record an album for them came when my girlfriend Liz met Chris Carter in a launderette. They only lived round the corner from us. He asked what Robert and I were doing and she said, ‘Well, they’re not doing anything at all at the moment’. And the next thing, we get a call from them, asking if we would like to do an album.”

Overdue a reissue after lying out of print for years, ‘The Bridge’ is a landmark record, and not just because it marked the only time Leer and Rental recorded together properly. It is an album of two halves: one half being noisy, TG-style sonic experiments, the other being a set of vocal songs that preface Leer’s more pop-leaning solo outings for Cherry Red, as well as the earliest Depeche Mode and Fad Gadget material.

Though the cover proclaimed boldly that it contained the sound of various home appliances, the principal kit used to give ‘The Bridge’ its distinctive sound came from the two EDP Wasp synthesisers that Leer and Rental both used on the album. The tracks were recorded at Robert’s Battersea high-rise flat overlooking the Albert Bridge, giving the album both its title and its sleeve image.

“We didn’t write anything before we started recording and we’d only been given two weeks to record the album, so we had to basically come up with a song a day,” recalls Leer. “We just got the gear, switched it on, and started playing around until we found things that worked. It was actually pretty crazy. In fact, to be honest, it was pretty much hell, especially the first week when we were doing the song-based tracks.

“The second side of the album was easier because that was pure improvisation. It was basically us just hooking up two tape recorders to make a giant loop, and then we fed sounds into it. The sounds would come back on themselves, gradually building up into a mulch that you could then use as a basis for doing stuff on top of. But my main memory of doing that album was that we put each other through a lot of pain.”

Were you still friends after the recording of ‘The Bridge’ was completed?

“Oh yeah, absolutely, I just didn’t want to work with Robert ever again!”

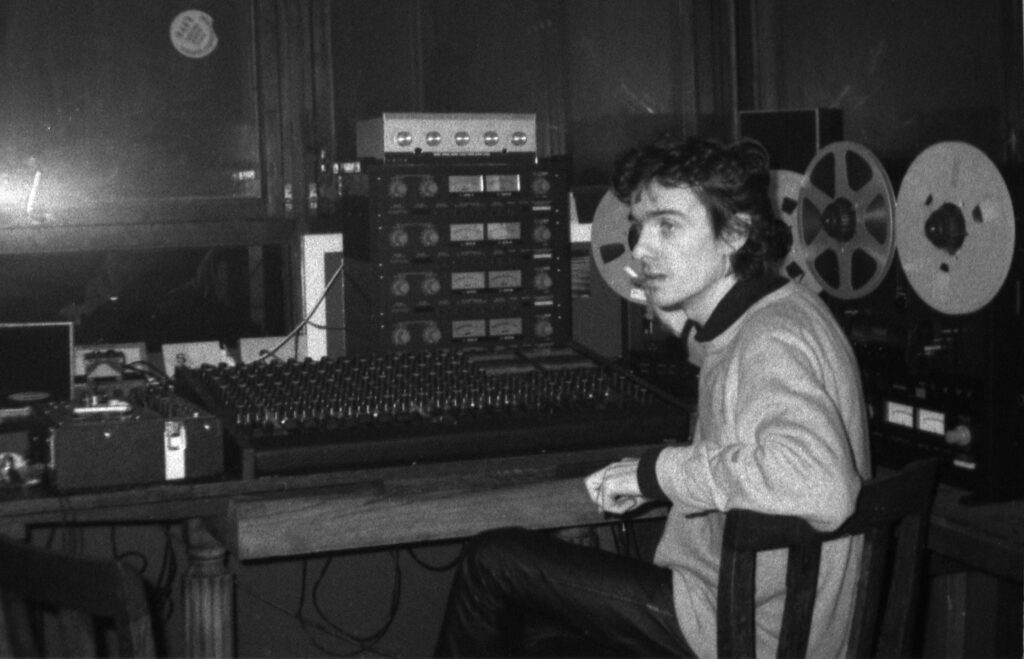

The pair would in fact work together once more, Leer playing piano on Rental’s solitary Mute single, ‘Double Heart’. He joined the sessions at Southwark’s Blackwing Studios, accompanied by Daniel Miller and Robert Görl, who played drums on the two tracks they recorded there in 1980. As with most Blackwing sessions of the time, they were presided over by Eric Radcliffe, the studio’s owner, and up-and-coming engineer John Fryer.

Leer’s girlfriend Liz designed the single’s sleeve, which shows a solitary Robert Rental in a darkened space, either a municipal car park or the entrance of a tower block. It is loaded with mystery and a perfect representation of this lone and often forgotten individual.

The ‘Double Heart’ sessions represented Rental’s first opportunity to work in a proper studio, and also his final properly recorded material. Leer says that Radcliffe and Miller “deserved a medal” for getting through it. The sense of slightly suppressed frustration, hinted at when Leer talks about ‘The Bridge’ and ‘Double Heart’ sessions, is also echoed by Daniel Miller. “Robert had a problem finishing tracks,” says Miller.

Reflecting his faith in Rental, Miller nevertheless encouraged him to record more over the following years, resulting in offering him studio time in Mute’s own Worldwide facility in 1990, 10 years on from ‘Double Heart’. The Worldwide sessions were overseen by Paul “PK” Kendall and Julian Briottet.

“Robert wasn’t particularly forthcoming with exactly what he wanted to achieve and I don’t think we made anything which could be considered finished,” says Kendall. “Daniel’s attitude was that it was an experiment, just to see if anything tangible appeared, and he wasn’t surprised when nothing emerged. For me, it was a personal disappointment.”

While Leer’s career flourished – both on his own, with Claudia Brücken in Act, and then once again as a solo artist – Rental’s abruptly ceased in 1980. The Worldwide sessions will likely never see the light of day. Indeed, very few people even knew that Rental had ventured back into a studio after ‘Double Heart’ was released.

Nevertheless, it transpired that he continued to develop new material at his Battersea flat, some of which emerged on last year’s collaboration with Glenn Wallis and on a new Optimo 12-inch release, ‘Different Voices For You, Different Colours For Me’, both showcasing hitherto unheard demos that were mostly never recorded properly.

Leer and Rental stayed friends while they were both still in London.

“We saw each other all the time,” says Leer. “But I didn’t have any part in his work after ‘Double Heart’, and he didn’t have any part in mine. We kind of separated off into our individual lives and partners.”

Robert Rental tragically died from lung cancer in 2000. He was only 48 years old. Because of his move back to Scotland, it had been around a decade since Thomas Leer had last seen his friend. He is still clearly pained by Rental’s untimely death.

“Although he didn’t do that much, he was quite important at that time,” insists Leer in conclusion. “It’s just not right that people don’t know about him. He may have played a small part, but it was an important one. He was a fantastic guy, Robert, no question about that. A very inspirational guy. He had a lot of great ideas and he used to inspire me to try things. That was really important to the way we worked together.”

For more info, visit thomasleer.co.uk. Robert Rental’s ‘Different Voices For You, Different Colours For Me’ is out on Optimo.