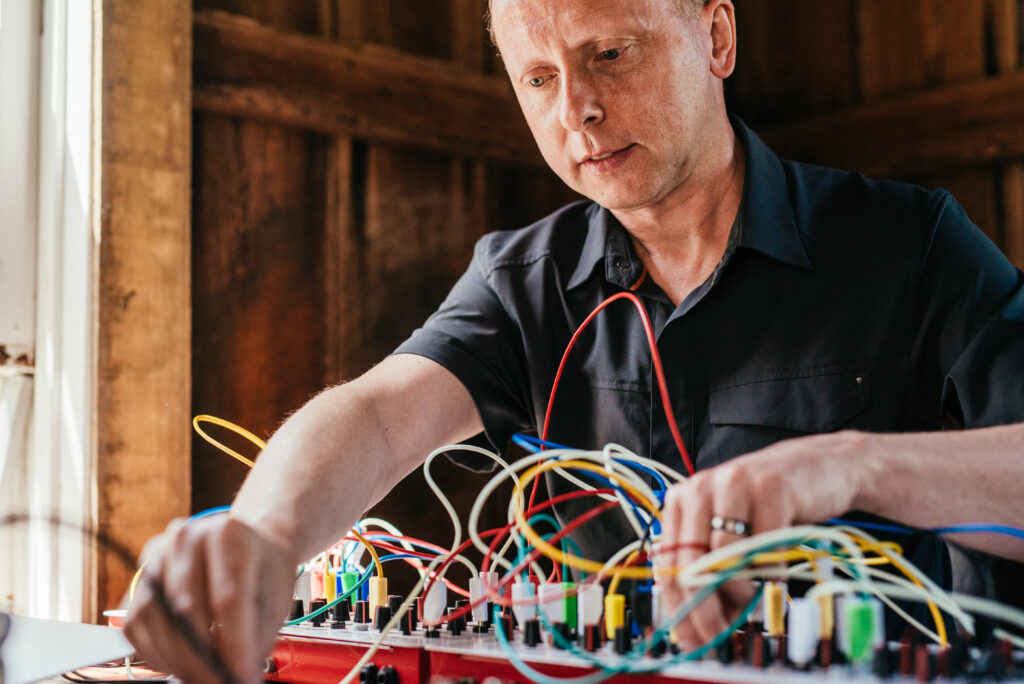

His voyeuristic 1995 ‘Mass Observation’ album broke all the rules and put Scanner on electronica’s top table. Some two decades down the line he’s still pushing at the edges. Robin Rimbaud talks life, the universe and almost everything…

“I remember sitting in a classroom listening to the Virgin Prunes and buying a Throbbing Gristle boxset when I was about 14 years old,” says Robin Rimbaud, aka sound sculptor, Scanner. “A friend of mine said, ‘That’s rubbish. It’s just noise. You should be listening to Hawkwind’, but music on the margins always interested me. I just had this inclination to the other.”

A compulsion to look beyond the obvious has been a driving force in Scanner’s remarkable career. Since the early 1990s, his untiring creativity has inspired not just a series of striking electronic records such as 1994’s ‘Mass Observation’ (sampled by Björk and widely considered a classic), but commissions for films, art exhibitions, installations, cinema adverts and much more. Rather than simply participate in a cycle of studio releases and live performances, Rimbaud actively seeks out new projects that will stretch his capabilities to the limit.

“I wouldn’t see my legacy as dependent upon compact discs and vinyl records over the years,” says Rimbaud. “I’m rather restless and I want new challenges, so I tend to say yes to things where it’s impossible to know what to do, and I tend to say no to people who say, ‘Would you like to come and do a concert?’.”

A chat with Rimbaud is stimulating, and full of digressions and asides. As we talk over Skype, he’s animated and his eyes sparkle with a fierce intelligence. In the background is the living room of his new home, a huge space converted from a 126-year old textile factory. It’s the first time he’s lived outside of London, and he’s enjoying the new start after a series of traumatic events. His mother and brother died within the space of two years, without any prior warning, and suddenly he had no family left.

The grief caused him to re-evaluate his life, and necessitated his move away from the capital. It also drove him to make ‘Fibolae’, a new album of sadness, anger and frail beauty that confronts the deaths of his family and friends.

“The week after my brother died I started working on this record,” says Rimbaud. “I was beyond despair; I didn’t know what to do. It’s a lot to deal with, all that stuff. There’s no one left who remembers me growing up, my childhood, my house. Absolutely no one. I was really angry. I wanted to make something that was ridiculously intense and cleansing in a way.”

The catharsis of ‘Fibolae’ is evident. It’s also very moving. From the fervent martial drums and samples of departed friends on opener, ‘Inhale’; the beautiful strings and double bass of the desolate ‘Eyeout’ and the booming electronic rhythms and spooky IDM of ‘Spirit Cluster’, it’s laden with uncontained feeling.

“To me, it’s really important that electronic music can have an emotional quality. What I wanted with ‘Fibolae’ was a record that has that emotional content, that really throws it at you.”

After his confrontation with tragedy, Rimbaud wanted his new home to serve another purpose: as an archive of his music and books for others to enjoy after he dies.

“It’s me being very ambitious for when I’m no longer around,” he says. “I have a very large collection of artist’s monographs and all kinds of books, a large record collection and a studio. What happens to all this stuff? So I thought, let’s build a foundation, with royalties I receive when I’m no longer here, to support other artists.”

Another new release, ‘The Great Crater’, has an entirely different muse. What Rimbaud describes as a commission work, it’s an ambient album for the label Glacial Movements, partially made with samples of ice melting and shifting. It too is mesmerising, though in a more low-key way. Here, the synths are more exposed, and a sense of menace drifts as slowly and inexorably as an iceberg beneath still waters on ‘Exposure, Collapse’.

“I wanted to tell a story in the sound,” says Rimbaud. “I found out about these weird shapes that were found on the ground in Antarctica, and that it was this worrying sign of global warming. The abstract sounds and weird textures are ice moving under the surface, expanding and contracting. I’ve always found these sounds absolutely fascinating, really beautiful, even though they are suggestive of something quite dark happening.”

Rather than simply make a statement with the subject and the method of composition, Rimbaud was keen for ‘The Great Crater’ to be something listeners would return to.

“I wanted to make something that was very listenable,” he says, “but at the same time I also wanted it to address a very unsettling subject. I want it to appeal to a listener to revisit again and again, rather than it be a polemic, or politically-driven record.”

The use of field recordings and samples drawn from the outside world is a theme that recurs through a lot of Scanner’s material. His most famous album, ‘Mass Observation’ (recorded with post-rock artists Jim O’Rourke and Robert Hampson, of the band Main), was acclaimed upon release, but also generated a fair amount of controversy thanks to its use of private phone conversations obtained via radio scanner.

A spectacularly immersive experience, it’s also creepy and voyeuristic as you listen in to snippets of phone sex and people talking about things they never thought would be broadcast to the world. In 2017, as the government snoops on phone calls and emails, and CCTV is everywhere, this “mass observation” has been normalised. In predicting an age of surveillance and voyeurism, the album has proven to be incredibly prescient.

“Those early records captured a moment in time, but yes, they anticipated a lot of thinking that’s going on today,” says Rimbaud. “What strikes me now is that our culture is that. It’s completely saturated in the media we look at, whether it’s on television or whatever. It’s a fascination with another world, and often the complete banality of another world. It used to be celebrities we followed and admired, and now it’s banal lives of people watching television.

“Those records were a picture of an ability to still have privacy, which you can’t really have any more. You could listen to a conversation in real time, and it’s not like you are on a bus or in the street; you’re in their private space. You’re listening to other people in their most private moments. There’s all kinds of questions to be asked about this, but there’s no other way in your life that you can be in that space with those people. You can never be in that environment. You can listen from afar.

“What fascinated me was, how we picture those people having those conversations. Everybody sees them in a different way. I began thinking, if I was to take those voices away, and just use the spaces they’re in, what could I find as well? So I began using the scanned phone calls and taking the voices away, and just using those radio soundscapes in a sense.

“There’s something really quite beautiful about it, because they’re always suggestive. It’s like when you flick through the radio in an old-fashioned way, and you get a crackling noise, which is rapidly disappearing. Moving through the static had a great sense of tension, because you didn’t know what you were going to set upon.”

Capturing the sounds of the world, whether they be people’s voices or ice cracking has been a preoccupation since Rimbaud’s school days, when he used to make tape recordings of his day-to-day life. Just recently, he’s digitised many of these cuts and has realised how important they’ve been to his sense of the world and his perception of audio in general.

“We would record ourselves, on the bus, playing football, all kinds of things,” he says. “I imported the tapes last year, and realised that those recordings are incredibly significant for me. They capture the environment – that landscape of sound in a way. I have recordings of my brother watching football on the television. He used to shout at the TV all the time. You hear me every now and then saying in my high-pitched voice, ‘Where’s the biscuits?’. Important moments in your life, questions we still ask today! What I was interested in, and when I listen back now, is that they are like portraits. Without realising it, it was a great inspiration to me and led me to think about my own work.”

This idea of capturing the sonic world would feed into his love of electronic music. In addition to the music of John Cage, Vangelis and Stockhausen, the young Robin Rimbaud became enraptured by the work of Brian Eno, and his album ‘On Land’, a series of audio depictions of locations around the country.

“Those Eno records, and other artists who follow these ideas, are able to capture space in a really interesting way.”

Field recording has become prevalent in electronic music and Scanner has a considerable claim as one of its greatest innovators. He’s inspired by the best examples of it – those recordings that help us perceive the world in a new way – but critical of producers who seek to exploit the idea.

“I was in Canada some years ago working at a festival, and a guy had this phenomenal sound installation of a series of seats set up in a space, and all around were these speakers,” says Rimbaud. “What they were presenting to you was a recording of the street outside. Part of me couldn’t help but think that if I was just to leave the gallery and stand in the street, it would be a much better representation of what I was hearing in the gallery, but it was about framing.

“It’s a curious thing; you can look at artists like Luc Ferrari, who was able to take tape recordings of what might be seen as very banal moments on the beach in Italy, of birdsong or people talking in a café, and structurally arrange them as these incredible works. You have someone like Bernard Parmegiani, the French composer who I’m a big admirer of, who would make recordings and create these worlds. There are also producers who are very lazy. They literally stand there with a recorder and release this thing. But what’s most fascinating about field recording is how it re-tunes our ears to listen.”

Get the print magazine bundled with limited edition, exclusive vinyl releases

Most of Rimbaud’s time these days is dedicated to unusual commissions, and he claims to work on around 65 individual pieces of work a year, sometimes more. He composed a piece for a contemporary dance work performed by 1,000 people at the London Olympic Games opening ceremony in 2012 (“It was fantastic, completely out there”), made sounds for a Philips wake-up light, and scored a ballet adaptation of Brothers Grimm fairy tales, in addition to many jobs for advertising.

Among campaigns for fashion houses Christian Dior and Stella McCartney, his composition for an advert (for mobile service provider Sprint) is his most high-profile project so far. It’s been played in every large cinema in the States, and seen by over two billion people. There’s a certain satisfaction in being able to make something completely abstract that’s been heard by more people than the biggest pop stars.

“These are ridiculous figures when you look at it,” boggles Rimbaud. “It’s unreal. You work in the most experimental way, and can be more successful than Taylor Swift or Lady Gaga, but no one’s ever heard of you. I love that. I love the fact I can mention this to people in the US and they can say, ‘I remember that ad, I didn’t realise that was you’. Listen to the Sprint ad. It’s completely abstract. I am so proud of the pieces, and to be able to do that, and to have it in every cinema in America for two years is phenomenal. And you’re not having to compromise at all.”

Rimbaud’s forthcoming projects are just as offbeat. He’s working on a tool for the EU Commission with artist Kasia Molga that measures soil moisture (and creates music and light in the process), an electronic score for a live play-through of video game, ‘Dear Esther’, and a soundtrack for a science-fiction film. There’s also the matter of his humorous memoir ‘Wrong Stories’, about the many mishaps encountered in his career.

“I thought it would be very entertaining to share these things publicly, and to show how easy it is to be humiliated,” he laughs.

The book was written while staying at pop artist Robert Rauschenberg’s house, like you do (sadly it’s a tale we don’t have time to go into here). Despite the trials he’s been through, Rimbaud seems notably inspired and positive about the future.

“Things continue,” concludes Rimbaud. “What I like is I remain someone who sits under the surface without any representation. I don’t have a record label, a deal, a manager, a publishing deal, an agent – those things that one arguably needs to succeed in music and the arts. But I feel really lucky.”

‘Fibolae’ is out on Pomperipossa, while ‘The Great Crater’ is out on Glacial Movements