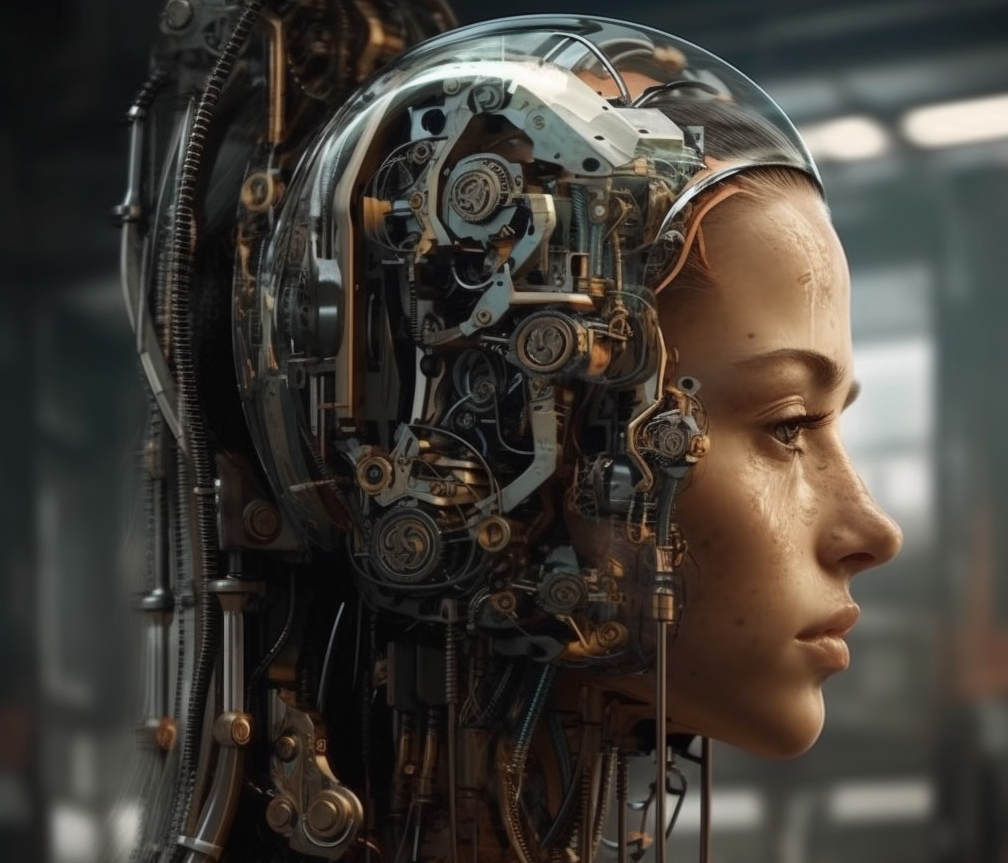

Digital explorer and presenter Aleks Krotoski muses on the potential of the internet and AI, the symbiosis between humans and machines, and how we might cope with the next steps in technology

Want to read more?

Sign up to Electronic Sound Premium to gain access to every post, video, special offers, and more. 100%, all you can eat, no commitment, cancel any time.

Already a premium member? Log in here