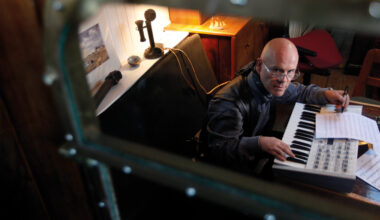

David Vorhaus remembers how a Summer Of Love encounter with Delia Derbyshire led to their foray into the counter culture with the White Noise album ‘An Electric Storm’

Just how swinging was London in 1967? Well, in January Michelangelo Antonioni’s film ‘Blow Up’ hit cinema screens, The Rolling Stones were the subject of a drug raid, which caught Marianne Faithful in a fur coat and nothing else, Hendrix set fire to his guitar for the first time on stage at a London gig, The Beatles released ‘Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band’, Pink Floyd put out their debut album, and the BBC started TV broadcasting in colour. That’s how swinging it was.

With all this going on, a young post-grad physics student and classically trained musician called David Vorhaus is heading to Morley College, just south of the river, for his weekly orchestra rehearsal. He plays double bass and is also interested in electronic music.

Born in the USA, his family had left the States in a hurry when Vorhaus was six because his father, the filmmaker Bernard Vorhaus, was being hounded by the FBI. Thanks to his anti-Nazi activities before the Second World War, he had been blacklisted for “un-American activities”. It’s a story worthy of a film in itself: while shooting ‘Hideout In The Alps’ in 1936 on an Austrian mountainside, Bernard Vorhaus and his crew were confronted by German troops wanting to arrest their Austrian guides for “anti-Nazi activities”. The guides promptly skied off down the mountain under a hail of bullets, one of which grazed Vorhaus’ face. Years later, in the febrile atmosphere of McCarthy’s anti-Communist witch hunts of the 1950s, this skirmish was enough for him to be deemed “prematurely anti-fascist”. He was blacklisted and harassed to give up names of fellow Commie travellers, prompting him to abandon America in a hurry.

The harassment didn’t stop when the family left. Following a stint in Switzerland, the police came knocking when they had been in Italy for a year, which prompted them to flee again and finally settle in the UK, where the young David excelled in his studies. At school, Vorhaus tore through the O and A level Music before tackling his other O levels.

“I found it interesting and easy,” he says. “I got 99 per cent in my class, which made me wonder what it was I’d got wrong. After that I started on my O levels in sciences, which is what I was planning on doing as a job.”

He didn’t know it, but his aptitude for science and music was setting him on a path that would lead him to Delia Derbyshire. His own dabbling had led him to “inventing tape editing for myself” a couple of years before he met her and Brian Hodgson in 1967. But making electronic music remained out of reach for the young physics student.

“It was a fantasy, I didn’t know anyone who actually did it,” he says.

This changed spectacularly on the night in question, when the college’s orchestra director told Vorhaus there was a lecture about to take place next door about electronic music.

“So I went along to the lecture,” says Vorhaus. “It was Delia, Brian Hodgson and Peter Zinovieff, and they were called Unit Delta Plus. It was fascinating. They were explaining how it worked and how one did it. After the lecture, I stayed behind to talk to them. I’m hopeless with names, but on this occasion it worked to my advantage, because I remembered Unit Delta Plus. I’d seen the name on posters earlier that year. So I said, ‘I know you guys, you were playing at the Roundhouse, there was a big poster up with Unit Delta Plus and some other guy’. And Delia said, ‘Do you remember who the other guy was?’ The other name hadn’t rung a bell, but it was Paul McCartney. I think that partly got me in there.”

He remembers Delia at that meeting as being “very English, in a slightly aristocratic way, but she wasn’t snobbish at all. She was well-spoken, no street cred there! She wasn’t the kind of person I knew, but we hit it off. We got on like house on fire.”

They got on so well, in fact, that a few days later, Unit Delta Plus had been dissolved, and Delia, Brian and David started a new venture together which they called Kaleidophon.

“Within a week we started building our studio,” says Vorhaus. “They wanted to do stuff they couldn’t do at the Workshop. My use to Delia and Brian was that I could actually build the equipment that they’d always fantasised about and wanted. It only existed in the Radiophonic Workshop, or didn’t exist at all. It was about saying, ‘It would nice if so-and-so existed, and then saying, ‘Why not?’ and building it.”

Previously, they’d relied on the expertise of Peter Zinovieff to come up with the equipment they needed to realise their sonic ambitions, but there were frustrations in their relationship with him.

“I think Peter was really more interested in computer technology, which was amazing stuff, but it was a bit far ahead of its time for actually making sounds,” says Vorhaus. “It meant that the studio was never actually working. They told me that in two years of the partnership of Unit Delta Plus, they’d only had one day in the studio when it was actually fully functioning. The rest of the time it was in construction mode, which I can see must have been very frustrating.”

To begin with, Delia and Brian would sneak Vorhaus into the Radiophonic Workshop studios in Maida Vale after hours to start work. At the same time, Vorhaus set about turning his bedsit in to a makeshift studio.

“I nicked a few large pieces of wood from the building site across the road where they were putting up skyscrapers, having pulled down the houses that we all lived in,” he remembers. “We divided the bedsit into a studio and machine area, and an area for sleeping and eating. As soon as we started working in there, somebody died in the room underneath, and then somebody else next door. Everybody thought this was what electronic sound did. It was like the 17th century, the villagers with their pitchforks! ‘We’ll burn you out if you don’t leave now!’. One of the people who died was 92 and the other was ill, but that was beside the point…”

While the makeshift studio was being put together, the illicit sessions at the Workshop produced several pieces of work, with Vorhaus learning the tricks of the trade from Delia.

“She was my teacher, and I was like a kid in candy store,” he says. “We had a very good working relationship.”

One mammoth 36-hour session, presumably over a weekend, saw Delia and Vorhaus working in shifts to complete music for the film of Yoko Ono’s ‘Wrapping Event’, where she wrapped the lions on Trafalgar Square in white cloth.

“We had to do it in a hurry,” he says. “It was like swimming the Channel. After 12 hours or so, one of us would cat nap, and the other one would be doing all the editing, then we’d swap over. We got through the session like that. I don’t have a copy of it, I don’t remember what we did. I haven’t heard it for over 50 years.”

Vorhaus also completed music for Ballet Rambert’s ‘Remembered Motion’, with their artistic director Geoff Moore, which was first performed in March, 1968. Vorhaus received the credit ‘Recording Treatment’. “I learned a lot doing that,” he says.

As Kaleidophon’s activities increased, Delia’s agitation at her position within the BBC intensified.

“Delia wasn’t happy at the Beeb and wanted to leave, more or less from when I first met her,” he says. “They didn’t take the Workshop seriously as proper musicians. And also, because she was a woman, she got a lot of ‘are you the secretary?’ attitude. They were never credited as composers, she’s not officially the composer of the ‘Doctor Who’ theme. They were called technical assistants, and they could only do the work they were given by producers. There wasn’t much choice about the kind of work they could do.”

As a result, her reputation as being difficult to work with started to gain more currency within the BBC.

“She did have a reputation for being difficult to work with,” says Vorhaus. “But she was very sensitive to being patronised. She didn’t get any of that crap from me. We got on very well, we could work on anything and come up with very good results.”

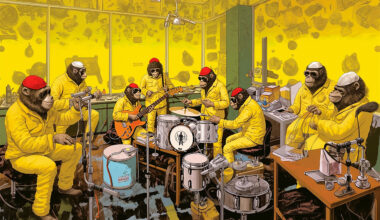

And so the trio continued taking on projects, using Radiophonic Workshop downtime. It was at one of the nighttime Workshop sessions that they came up with two tracks, ‘Love Without Sound’ and ‘Firebird’, which were the beginnings of what would become the White Noise album, ‘An Electric Storm’.

“I don’t think the album happened immediately,” says Vorhaus. “But sometime within that first year we thought it would be great to do a couple of tracks and take them to a record company and see it how it went.”

Vorhaus took the tape of the two tracks, recorded in mono, to Chris Blackwell at Island Records. Vorhaus wanted the two tracks to be released as a single, and for it be a hit.

“I said, ‘I want it to be on the radio, and be famous and all that’,” he laughs. “He told me I was crazy, that it wasn’t a single and that we should do an album. He was right of course, I was very green in those days. He told me that, on the whole, singles sold to 12-year-olds, and that singles really were testing grounds, and if you have a hit single you can go off and do an album. Then he worked out what the average Number One single made, which was then about £3,000, maybe about £60,000 in today’s money, wrote me a cheque for £3,000 and said, ‘Here, you’ve had your hit single, now you can make an album.”

It’s a tale of the long gone glory days of record company largesse, and the money enabled Dave, Delia and Brian get Kaleidophon off the ground in earnest, taking a premises on Camden High Street where David could build a proper studio and where they could make the White Noise album without the BBC breathing down their necks. With a major label advance and a new studio, it must have seemed like the perfect time for Delia to jump from the good ship BBC, but Vorhaus talked her out of it.

“I’m afraid I was the one responsible for getting her to stay there,” he confesses. “She had a good salary, she was on about £3,000 a year, which was an astronomic amount. As a graduate physicist, if you were lucky you might get £1,000 a year, probably more like £900.”

That wasn’t his only motivation for getting Delia to stay at the Workshop. There was a piece of gear there he coveted…

“You couldn’t buy it or make it,” he says. “It had been put together over many years by a group of top BBC engineers. It was designed to stop howlround or feedback from PA systems. They had the bright idea that if they shifted the frequency up a few cycles before it comes out the speakers, then it’s something different that comes out that went in, so it won’t feedback. Don’t forget this is still the valve days of electronics, and it would have cost millions in today’s money.

“They finally unleashed this thing on some big event, and to their horror not only did they get howlround, but it would go up and and up and up, or down and down. It was completely useless. So they dumped it at the Radiophonic junk shop in disgust. We found that if you put a tape loop into it so that it plays back shifted, you get this controlled howlround, except it’s not howling. A good example is on ‘Love Without Sound’, the sound between the vocals was treated with it. That was the frequency shifter, nobody had ever heard a sound like that.”

The world would have to wait a while to hear this new sound. Delia, Brian and David started work on their album in 1968, but still hadn’t finished it nearly a year later. They had the two initial tracks made at the Radiophonic Workshop, ‘Love Without Sound’, the gorgeous ’Firebird’ and the tape cut-up pop freak-out of ‘Here Come The Fleas’.

“We worked ‘Firebird’ out together on Delia’s spinet in her flat in Clifford Gardens, which was between my flat and the Radiophonic Workshop,” explains Vorhaus. “The opening of ‘Here Comes The Fleas’ was pure Delia. The fast cut-up stuff sounds kind of synthy, but we didn’t have a synth, they were bits of tape cut together of various recordings, some I’d made, some sound effects, some were early Moog records. That was me, many evenings spent chopping.”

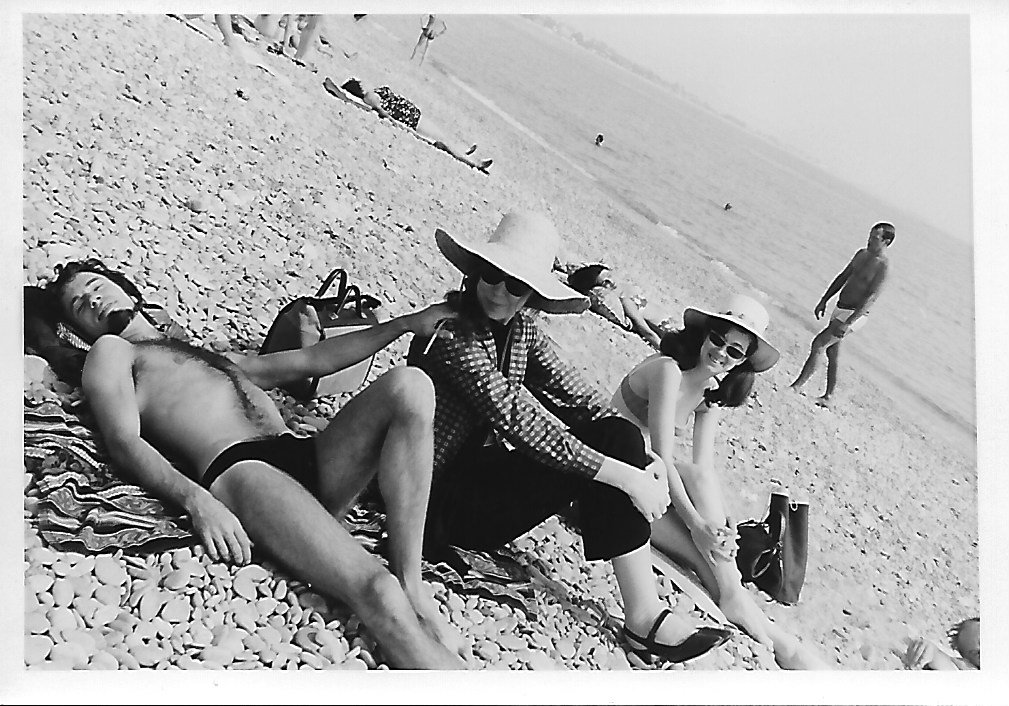

They’d also completed one of the more notorious tracks on ‘An Electric Storm’; ‘My Kind Of Loving’, a psychedelic orgy spliced into ‘Smile’-era Beach Boys-esque baroque pop that ends, humorously, with snoring.

“That track started with me cruising Swiss Cottage Public Library for anyone who could write lyrics,” chuckles Vorhaus. “I saw this gorgeous American girl, Georgina Duncan, who was doing a post-grad in English, she wrote poetry. I said ‘Poetry! Fantastic! Can you write lyrics? I’ve been commissioned to make this album and I desperately need some lyrics. Come up to studio and show me what you’ve got’. What a line! She came up with ‘My Game Of Loving’, which was perfect. So then I had to cruise Camden High Street to find nice ladies that could speak in lots of interesting foreign languages to give us a French version, a Swedish version, a German version and so on of one of the lines. I’d take them up to my studio, and in between fun and games get them into the recording studio to do their lines. What a life!”

I put to him that it’s like ‘Blow Up’ with David Hemmings going around London photographing beautiful women and then rolling around in his studio with them in the nude.

“Yes! Exactly! That’s precisely the way it was! It was very much the 60s philosophy, and that’s how that record got made, including the orgy. When there was enough of us we all had a big orgy, and then I cut out single sounds from that and made the artificial orgy, the loop that became orgiastic, so there’s two orgies in there, one sort of synthesised from the other which is real, and yeah… great fun.”

Did Delia contribute to this particular track?

“Of course! Everybody always asks me if Delia was in the orgy, but I’m not answering the question.”

Was she delighted with the results, though?

“Yes. She definitely approved. The bottom line of course is the record. It was great fun getting there.”

Less fun, however, was the letter they received from Island asking where the album was and threatening legal action.

“We hadn’t heard anything from them, no phone calls asking how we were getting on, whether we needed any help, nothing,” says Vorhaus. “And then this letter arrives saying if we didn’t deliver the finished product within seven days, their solicitors would be taking action to recover the advance. Charming. And so I thought, ‘We won’t take a week, we’ll finish it in a night.’ I got a friend of mine, Paul Lytton, to record a drum loop, and then played the loop live and threw in the nastiest sounds, the screams, all the nastiest stuff you could create and imagine. That was ‘The Black Mass: An Electric Storm In Hell’. It all happened in a night, and the next day we gave Island their album.”

When ‘An Electric Storm’ came out, it tanked. At the time, Guy Stevens was in charge at Island – the supportive Chris Blackwell was away – and he didn’t like the album at all and decreed that it should receive no promotional muscle.

“Nobody heard it or knew anything about it when it first came out,” says Vorhaus. “It sold a couple of hundred copies in the first year and we thought, ‘Well, at least we got the advance, and that’s it, and we can get on with our lives’. But it gradually it got around by word of mouth. Particularly the underground DJs off the coast, the pirate stations, like Radio Caroline. Kenny Everett must have played it a thousand times. It gradually picked up over the years and gets re-released regularly. It’s definitely my longest-selling album ever.”

The Kaleidophon partnership produced another album in 1969 for the Standard Music library, ‘Electronic’, a series of electronic music cues intended for use in TV programmes, and indeed a chunk of it was used for the ITV children’s sci-fi show ‘Tomorrow’s People’ in the 1970s.

Delia faded out of Kaleidophon, which Vorhaus has since maintained alone, scoring films (including the last Powell And Pressburger movie, ‘The Boy Who Turned Yellow’ in 1972) and creating new possibilities and equipment for electronic music. Delia eventually did leave the BBC of course, but never really joined Brian Hodgson in his post-BBC/post-Kaleidophon venture, Electrophon, as they had planned. However, the work she did with David Vorhaus and Brian Hodgson lives on, re-released every few years and finding new listeners each time to be astounded by what could be achieved 50 years ago with tape machines, electronics and, of course, an orgy.