As comic-book lab scientists Devo celebrate their 50th anniversary with a new boxset of archive treasures, they’ve also announced a farewell tour. Have the spudboys really run out of sap?

Kent State, Ohio, USA, 1973. The Creative Arts Festival is underway at the university’s Recital Hall. It’s a multidiscipline event of theatre, poetry readings, concerts and workshops.

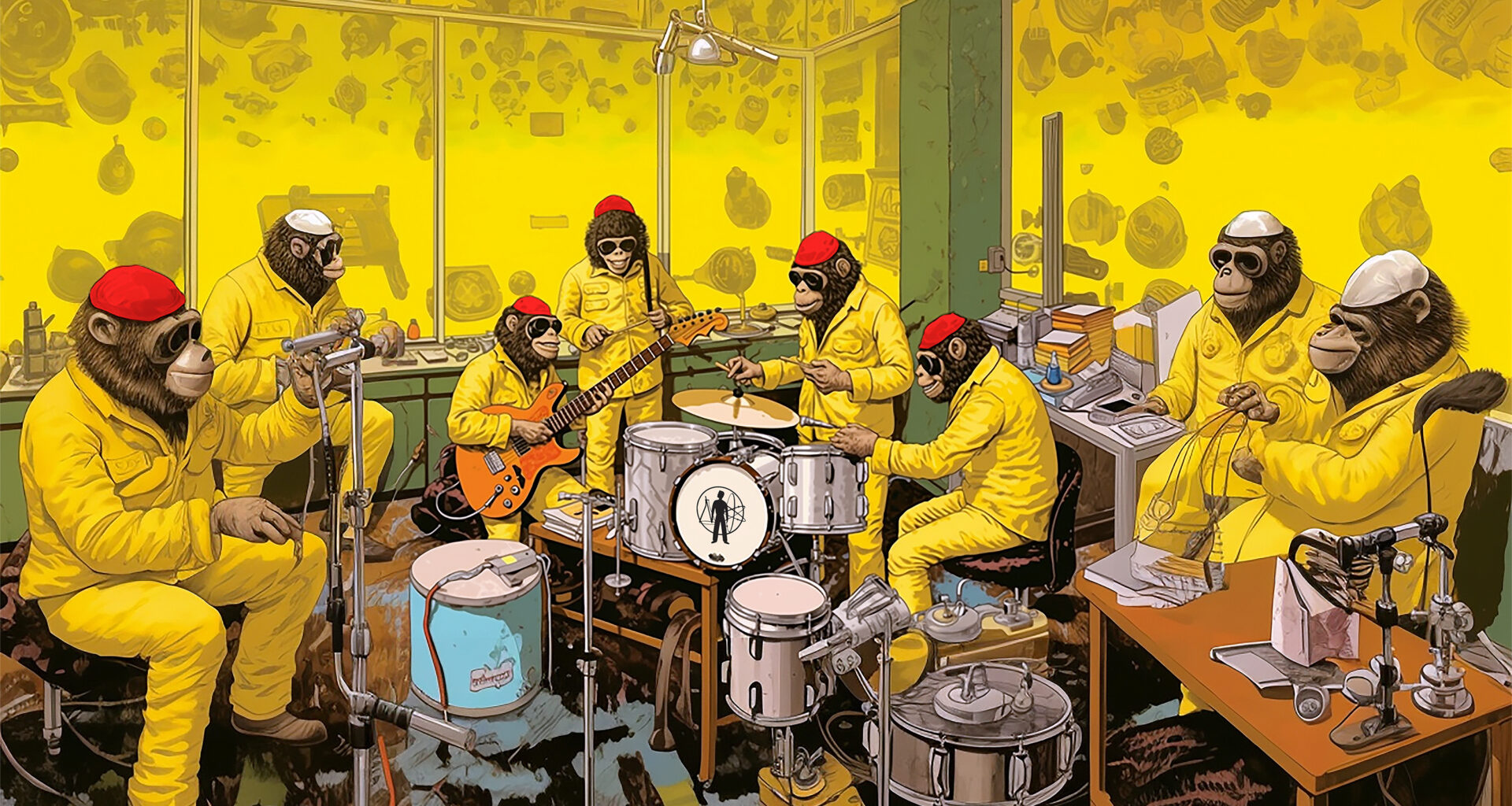

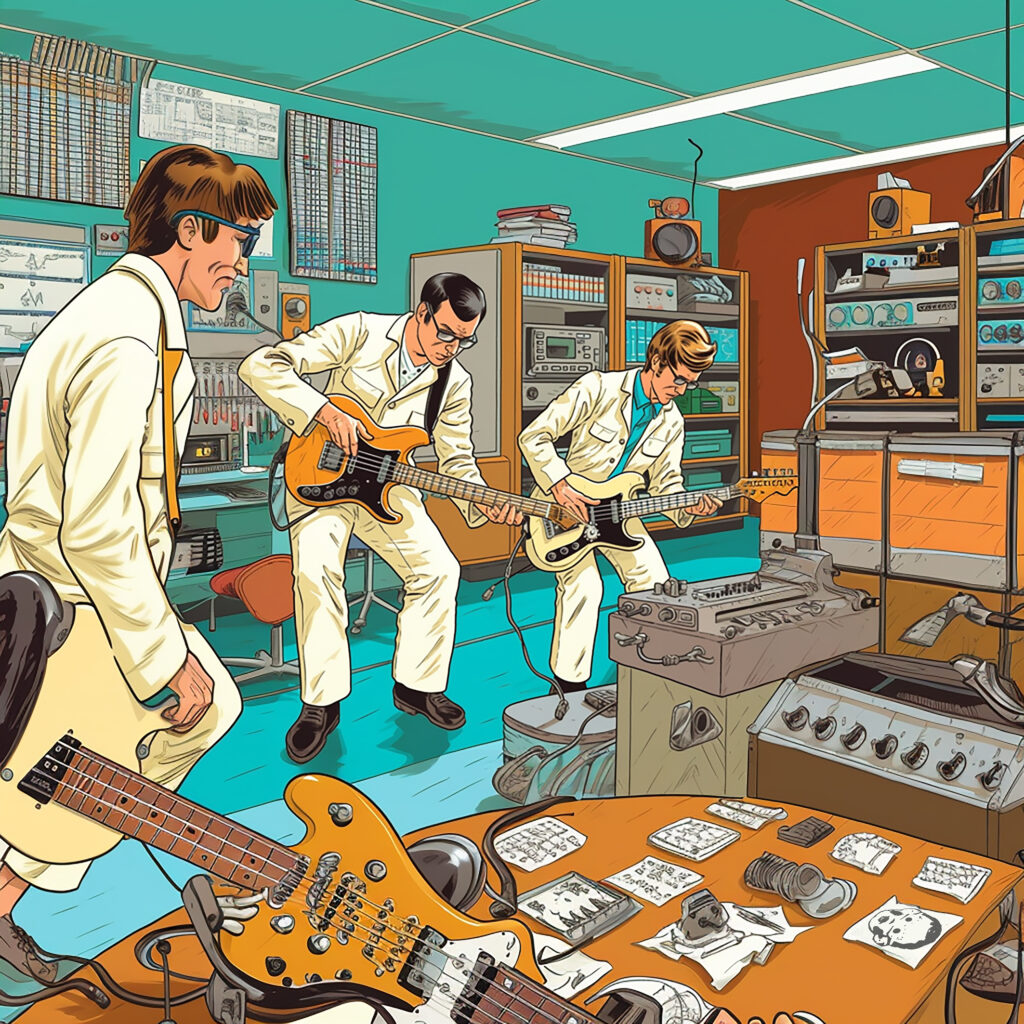

On 18 April at 7pm, a mysterious new performance troupe takes to the stage. Gerald “Jerry” Casale, the bass player, is wearing a white lab coat. The keyboard player, Mark Mothersbaugh, his head inside a monkey mask, manipulates a Minimoog to produce obscene moist squelches and honks. It sounds like the venue’s plumbing is about to unleash a torrent of human waste. The drummer bashes out a rudimentary rhythm, the guitars chug away with a swampy blues riff. The Minimoog starts impersonating an air raid siren howl for several deeply uncomfortable minutes.

The sparse audience of long-haired students is bemused, appalled even, but strangely transfixed. This isn’t the usual bar band knocking out covers of Led Zep or Foghat, the English blues rock band so mysteriously adored in early 70s America (and largely ignored in the UK). This is Sextet Devo, a homegrown mutation that started weird and is only going to get weirder. According to the event programme, they are performing “polyrhythmic tone exercises in de-evolution”.

From this rough situationist debut, Casale and Mothersbaugh spun the Devo music/art project from a basement in Akron, Ohio into a 50-year rock ’n’ roll sideshow and devolutionary think-tank, infiltrating the pop biz with their crank theory of de-evolution and lobbing satirical grenades at American society. Somehow, despite a sizeable chunk of the US music industry gatekeepers hating them with a visceral intensity, they also had hit singles and sold millions of albums. Half a century later, Casale and Mothersbaugh are celebrating their crackpot idea – five decades of de-evolution and spiking America’s mainstream with brainiac Kool-Aid.

Despite their mechanical presentation as suburban robots, time has had its way with Devo. Drummer Alan Myers, who left the band in 1985 after the ‘Shout’ album, died of cancer in 2013. Bob Casale (aka Bob 2), brother of Gerald, died the following year of heart failure. Now down to just three members of the classic line-up – Gerald Casale, Mark Mothersbaugh and his younger brother Bob Mothersbaugh (aka Bob 1) – the band is playing a series of dates in Europe this summer, a jaunt that’s been promoted both as a celebration of their anniversary and as a farewell tour.

At the same time, ‘Art Devo 1973-1977’, an elaborate boxset containing previously unreleased pre-record deal demos and early live gems, is being released by Futurismo. Fittingly for an outfit whose modus operandi is more closely aligned to an art movement than a band, the collection resembles a high-end auction catalogue for a major retrospective more than it does your regular pop disc compilation.

But first, the “farewell” tag needs some explanation. Is this really goodbye?

“That ‘farewell’ idea was floated to us,” says Casale. “But I said if it’s farewell, then it needs more money, bigger production and new songs. But no one was interested in that. It’s like business decided – ‘These guys have been around 50 years. Yep, it’s farewell!’.”

“It’s really irritating to me, because that’s the lamest thing you can say about something,” says Mothersbaugh. “But we’re thinking of this as the kick-off for the next 50 years, which I want to call ‘Mutate, Don’t Stagnate!’. That’s my take on it. And it’s a positive message for kids that are going, ‘What the hell’s going on in the world these days?’. They’re trying to figure out where they stand and what their place is. I think we need to address that and be creative about it.”

Mothersbaugh is in his early 70s now, which might make fronting Devo for another half century something of a challenge. But he has a plan…

“Sometime in the next 15-20 years, I’m probably going to have to migrate from a flesh body into a much better AI body and move all my sentient thoughts in there,” he says. “So will the rest of Devo. But the good news is we can probably have our instruments incorporated into our new physical being, so setting up the equipment… there will be nothing to it!”

More immediately, will these anniversary concerts be showcasing tracks from across the extensive Devo back catalogue?

“You know,” he replies, “if the ghost of David Bowie came up to me tonight and said, ‘Mark, I’m going to play a concert for you with all the players I’ve met here, wherever I am in this other world I’m living in now, and it’s going to be a brand new album that nobody’s ever heard’. Or, ‘I can do ‘…Spiders From Mars’, and I’ll use all the original guys from the Spiders and we will play that show you saw at the Cleveland Auditorium and we blew your mind’. I’d go, ‘I’ll pick ‘…The Spiders From Mars’.

“That’s what people want to hear. With new songs, they’re like, ‘We’ll put up with one of those as long as we get to hear ‘Uncontrollable Urge’.”

It’s safe to assume that Mothersbaugh won’t be punishing audiences this summer like he did back in 1973 at that Creative Arts Festival, though he remembers the gig fondly.

“There’s a section where the guys went backstage to tune their guitars,” he recalls. “And I was doing something onstage I called ‘The Headache Song’. I’d make a sawtooth go in reverse and forward, so it was going ‘Boing! Boing! Boing!’.”

He imitates the sound.

“It was just to fill in the time while they were offstage tuning up. And I’m thinking, ‘Man, it’s taking them forever’. What I found out later is that the synth was so loud backstage that they couldn’t tune their guitars. So it just meant the audience got an extra three or four minutes of headache.”

That set the tone for what was to come, performances where the tension between audiences expecting a bar-room cover band and Devo’s wild sound and presentation energised the de-evolution project to further extremes. It marked the beginning of the era which spawned the output captured on the ‘Art Devo’ boxset.

“We were definitely looking to get people’s attention,” says Mothersbaugh. “We weren’t looking to do something pretty, we wanted to be confrontational. A few years before that show we were students at Kent State where the National Guard shot kids who were protesting against the war in Vietnam. That was an upsetting scenario for us. And it kind of helped set the tone for the band, in a way. So the idea of being provocative was something we were trying to attain.”

The debut gig turned out to be the only Devo performance of 1973. There was another show at the following year’s Creative Arts Festival, by which point Devo had become a family affair, with Mothersbaugh’s brother Jim stepping in on drums, and Bob Mothersbaugh and Jerry’s brother Bob Casale (Bob 2) also on board.

Things started to hot up towards the end of 1975. As ‘Art Devo’ showcases, the tape stash of demos, sketches and live recordings was growing, ranging from 4-track home recordings to low-rent studio efforts, and then on 31 October, they experienced an early turning point at the WHK Auditorium in Cleveland, Ohio.

Devo had conned their way into a booking supporting Sun Ra at the WHK radio station’s Halloween party. The show, which lasted all of four songs, was recorded by the band and released in 1992 by Rykodisc as part of the ‘Devo Live: The Mongoloid Years’ CD.

“That was one of our most frightening nights,” recalls Gerald Casale, laughing. “I had lied to promoters, saying we were a covers band to get the gig. I was articulate, and I could act like a straight guy. So we got booked. And we come onstage wearing grey fireman jumpsuits and these masks that Mark had found. They’re just clear vinyl, with painted eyebrows and lips, and they turned you into this kind of semi-robotic, French masquerade kind of creep. And Bob Mothersbaugh had found these plastic hard hats. Together, the whole ensemble really was kind of like ‘Metropolis’.

“And we come on like that to this rock ’n’ roll crowd that’s there for a radio station Halloween bash, and they’re all insiders – part of the Cleveland scene and the big promoter. It was a costume party and they were all doing nitrous oxide. So they’re in these typical costumes – Frankenstein, Wolfman – and the women are, of course, dressed like prostitutes. And I go, ‘Here’s one by Bad Company’, and then we opened with ‘Be Stiff’. For about a minute, they’re all kind of into it until they realise, ‘Wait a minute… Bad Company? I never heard this song!’. I forget what the second song was. But now there’s grumblings and people shouting out things at us.

“So Mark signals and he goes, ‘Let’s just go right into ‘Jocko Homo’, and of course we’re all game for that. You can imagine! That did it. By the time we get to the kind of jungley, four-on-the-floor chant, ‘Are we not men!’, they’re like, ‘You’re not men, you’re fucking assholes!’.

“And then some of the bigger guys dressed as Frankenstein monsters and the Hunchback of Notre-Dame come right up onstage. They grab the mic from Mark and start pushing us around, and then our roadies jump up and try to run interference for us. Beer bottles start to come from the crowd and are landing on the stage. And of course we exit and our road crew is still struggling with these guys, trying to get them not to ruin the equipment. Then they all start cheering because they successfully got us off in less than 15 minutes.”

Being attacked by enraged partygoers dressed as monsters and high on nitrous oxide was the evidence Devo needed to justify their de-evolution theory – man was regressing, not evolving. They were energised by the experience. They had unleashed the power of confrontation. Jim Mothersbaugh, however, had no stomach for provoking audiences into attacking him. He was not onboard and left after the Halloween gig, refusing to play any more. He was replaced by Alan Myers, perhaps the finest drummer of the entire post-punk era.

While we have you, why not take a minute to browse our online shop?

We’ve got print magazines, limited edition vinyl, must-have books, CD boxsets, and we ship worldwide. Click below to open a new tab and keep your current reading place.

The new boxset, ‘Art Devo 1973-1977’, represents the deepest dive into the Devo tape stockpile yet undertaken. The archives were thought to have been hollowed out for the two volumes of so-called ‘Hardcore Devo’, made up of 40 tracks recorded during the band’s pupa phase in Akron and released in the early 1990s. But ‘Art Devo’ presents another 46, many of which have never been previously released.

“We thought there was nothing left,” says Casale. “Our archivist guy, Michael Pilmer, and one of his friends, Alex Brunelle, they dug up this stuff that we didn’t think had survived. A lot of it nobody has ever heard before.”

There are early versions of tracks which emerged years later on studio albums, snippets of experiments, and plenty of unruly transgressive material across the three-disc set. For example, the song ‘Death Of Lt Casanova’, the opening couplet of which Casale narrates as the slow bassline lopes along and Mothersbaugh’s synth wobbles and squirts – “They found him dead / With her panties on his head”. Part of this bassline was later repurposed for ‘Smart Patrol’, a live favourite eventually released on the band’s second LP, ‘Duty Now For The Future’. Another track on ‘Art Devo’ is the frenetic ‘Huboon Stomp’, which includes the lyrics, “Well, I’m a huboon baby! / I’m a cross between a human and an ape!”.

“We were, as they would like to say these days, unfiltered and politically incorrect,” chuckles Casale. “This stuff wasn’t coming from a position of misogyny or homophobia or white supremacy. We were just acknowledging the insecurities and grievances and, you know, insights that one might have if you’re not powerful, if your dad doesn’t run the town.”

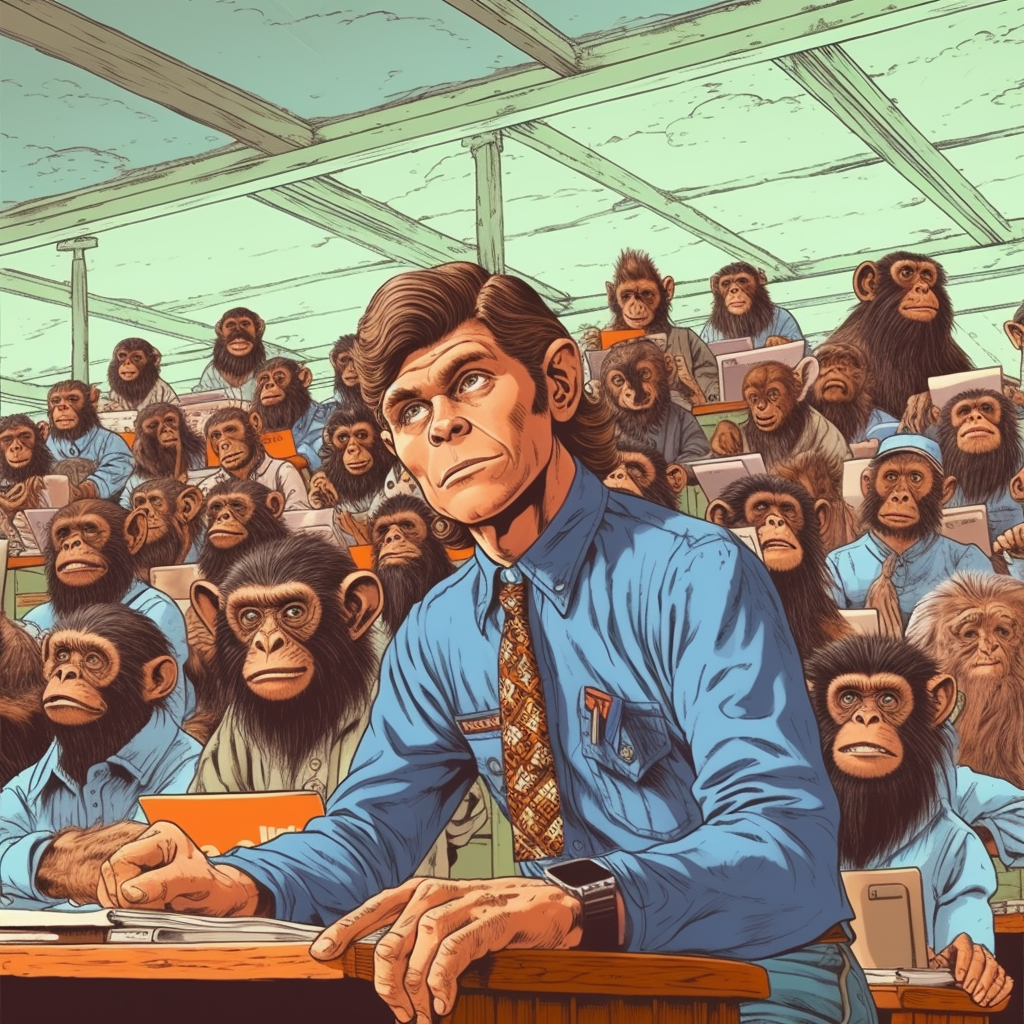

They were able to openly peddle this outrageous content because in Akron, Devo had the dubious advantage of not being in anyone’s spotlight. The band evolved in the stinking environs of a working-class city built on the rubber industry and now in decline. No one was interested in anything that happened there. As a result, Devo was a one-off, with ugly protrusions and a misshapen anatomy which they exaggerated with masks, costumes, and talk of spuds and mutations.

“Nobody gave a shit about us,” says Casale. “They either felt sorry for us, or they hated us. So we were free. We luckily had this gestation for four years. Nobody but us and a few of our friends were paying any attention, or even hearing us.”

External influence on the Devo project was achieved by heading to Cleveland, 40 miles from Akron, on the south shore of Lake Erie, to catch bands as they toured the US.

“We saw Bowie, Queen, Slade – everyone,” remembers Casale. “I’m so glad I saw everything. You start to get objective, or at least I did. Like, ‘We think we’re artsy, but look at these guys. Look how well they communicate, how well they play and how well they put out what they want to put out. We have to do what we do as good as what I just saw Slade do’. I was almost crushed when I saw ‘Diamond Dogs’. Humbled and jealous. We were nothing. Nothing.”

A lot of the material was yet to encounter the amphetamine intensity of punk, which was the final piece of the jigsaw Devo needed to complete the picture. On ‘Art Devo’, there’s an early rendering of ‘Uncontrollable Urge’, which feels like it’s wading waist-high through mud compared with the version they wowed audiences with in the second half of 1977.

“Yeah, I love that! It’s like, ‘Uncontrollable Dirge’,” enthuses Casale. “I remember that was one of the first songs Mark ever wrote alone. It sounds like a kind of academic sketch. This needs an injection of cocaine!”

You can hear Casale and Mothersbaugh entertaining each other on these recordings. On ‘Shrivel Up’, another song whose tempo was ramped up when they recorded it for their debut LP, Mothersbaugh sings in a peculiarly lilting yet sinister voice.

“He took off with it,” says Casale. “I used to like it when he did character voices, and he started doing it in this kids’-TV-show-guy voice. Like he’s talking to pre-schoolers, but with lyrics like that. It’s fantastic that he’s using that voice to say those things.”

Those lyrics being dark warnings that your parents are going to die and you are also running out of sap. At this point, Devo’s perverse sense of humour, weird songs and outsider status wouldn’t have marked them out for becoming the band most desired by the biggest record labels in the world. But 1977 was about to change everything.

In 1977, after only half a dozen or so local gigs in 1976 and yet more basement recordings, Casale’s straight-guy manager schtick was in overdrive. By now, the line-up was settled as the Casale brothers, Mark and Bob Mothersbaugh, with precision drumming courtesy of Alan Myers. Punk had ripped through the music scene, and Devo’s bpms were surging.

‘Uncontrollable Urge’ was now delivering on its Beatlemania promise. ‘Smart Patrol’, the 1974 slo-mo version of which is on the boxset, was also now on fire and segued into the frantic thrashing of ‘Mr DNA’, sending crowds into frenzies. And their messed-up rendition of The Rolling Stones’ ‘Satisfaction’, which on tape in 1976 had been positively funereal, was now a furious math-rocker turning people’s brains inside out. The band secured a run of dates in New York, where the buzz was getting fanatical.

The word extended to Los Angeles, where Warner Bros and A&M Records were showing interest. From LA, the band went to San Francisco and played two nights at a venue called Mabuhay Gardens, a former Filipino restaurant which had become a punk rock hotspot, hosting gigs seven nights a week, with early and late shows. One of those shows was recorded, and a tape made its way to London where it landed in the tape deck of Jon Savage, star writer at weekly music paper Sounds.

Savage had been writing about punk for Sounds, but such was the velocity of the music scene at that time that punk was rapidly becoming yesterday’s news, and Savage, already bored with The Clash, was on the lookout for the new sound.

“As far as I was concerned, electronic music was the future,” he says.

Bowie’s ‘Low’, ‘Magic Fly’ by Space, the Donna Summer/Giorgio Moroder masterpiece ‘I Feel Love’ and Kraftwerk’s ‘Trans-Europe Express’ had all been released in the first half of 1977 and were making punk feel old hat to Savage. So he was all ears when he was sent the recording of Devo’s explosive Mabuhay Gardens show.

“I was a huge fan of fanzines,” he explains. “So I was in touch with Greg Shaw who did the Who Put The Bomp fanzine, Claude Bessy who did Slash, and also Val Vale from Search & Destroy in San Francisco. I think it was Greg Shaw who made the recording of the August Mabuhay Gardens show, and it was certainly him who was distributing it.

“The actual performance itself is pretty great – I think it’s the best thing they ever did. It’s very raw and uptempo and rocking, and also very psychedelic. That’s what attracted me. I liked all the synthesiser whoops. And synthesiser noises on top of these insane guitar riffs, particularly the ‘Gut Feeling’/‘Sloppy’ segue. Just incredible. But the rest is pretty good. You got the odd audience participation in ‘Praying Hands’. You’ve got the breakdown in ‘Too Much Paranoias’. And the version of ‘Jocko Homo’ is incredible.”

Savage played the tape to Paul Morley – yet to become NME’s enfant terrible – who had a fanzine called Girl Trouble, for which Savage wrote probably the first Devo piece in the UK, and word spread fast.

Rough Trade were keen on the Mabuhay Gardens tape and were distributing copies of it. The noise around Devo in New York and LA had spread to London, and Savage consolidated it with his and Jane Suck’s 26 November takeover of Sounds, a manifesto which rejected punk and ushered in the era of “New Musick: The Cold Wave”. The cover photo that week was Ralf Hütter and Florian Schneider of Kraftwerk, and inside they reprinted the Girl Trouble article, itself partly assembled from snippets of an earlier Search & Destroy piece.

Savage wound up the year by putting the Mabuhay Gardens recording on his end-of-year Top 10 in Sounds.

Meanwhile, in the US, Bowie was raving about Devo, and when they returned to play a run of dates at Max’s Kansas City in New York in November 1977, he publicly promised to produce them himself, in Tokyo.

A bidding war between several labels duly erupted. A&M dropped out, Island would be rejected, but Virgin and Warner Bros were both in the running and Bowie’s Bewlay Bros management company were also in the mix. Against this febrile backdrop of business combat, and with Bowie bowing out due to his packed schedule, a still-unsigned Devo decamped to Conny Plank’s studio near Cologne to make ‘Q: Are We Not Men? A: We Are Devo!’ with Brian Eno producing.

Warner Bros thought they had Devo in the bag, but Virgin had other ideas. Simon Draper, then Virgin Records’ Number Two and head of A&R, visited Plank’s studio during the recording of the album, and recalls the air of tension and the sharp-elbowed battle to add Devo to their roster.

“We were very, very keen to sign them,” says Draper. “They were the hottest thing around. There was huge competition to get them. Warner Bros were the main movers, so I went out there just to meet the band and try and get them on our side.

“I remember it was quite an intimidating atmosphere, because they were full of character, real personalities. Conny Plank was a bit of a legend as well. But I was just sitting and listening, and basically making approving noises because it sounded very exciting to me. We were trying to sell ourselves to them.”

The wooing campaign took on ludicrous proportions when Richard Branson flew Mark Mothersbaugh and Bob 2 out to Jamaica where he tried to talk them into having John Lydon as their singer.

“I thought it was a completely and utterly mad idea,” laughs Draper. “Doomed to total failure. Where was he supposed to fit in? I cannot imagine. That is a crackpot idea, isn’t it? I mean, they already had a singer. Or two.”

“He wanted to smash our two bands together,” says Mothersbaugh. “In retrospect, I wish we had done it for one day, gone into a studio and done something. That would have been fun. But he caught us off-guard because he didn’t tell us before we came down there. So it was kind of like, ‘Oh shit!’.”

Jon Savage also travelled to Germany to meet them and write their first major UK music press feature.

“It was the middle of winter, and in the middle of Baader-Meinhof,” remembers Savage. “It felt very cold, very threatening. I was plunged into this ridiculous situation, and of course they behaved like complete assholes. It didn’t stop me liking what they did, but it taught me never to interview band members together. The next day, Gerald Casale relented and gave me a good one-to-one interview. I’m sure they were finding the whole situation very difficult to deal with.”

In that interview, Casale told Savage that he could play him Devo tapes from three years earlier, with drum sounds reminiscent of the kind of thing Bowie was doing on ‘Low’.

“There is that whole hinterland of stuff they recorded, some of which is pretty great,” says Savage. “You have these people making really insane recordings in almost complete isolation.”

After a tense month of wrangling, Devo signed to Virgin for the UK and Europe, and Warner Bros for the Americas and Japan. While the world waited for the album to drop, Stiff Records licensed their self-produced DIY single ‘Jocko Homo’ and then ‘Satisfaction’, and sold shedloads of both. The Mabuhay Gardens tape appeared as a vinyl bootleg and did brisk business in many record shops across the UK. An unofficial seven-inch EP, ‘Mechanical Man’, also popped up, featuring songs from the 4-track demos of the mid-1970s.

A further pirate live release followed in 1978, this one with a full-colour cover and insert. Credited to Workforce To The World with the title ‘Live! On Site’, it was another recording from Mabuhay Gardens, with additional tracks from a performance in Cleveland and the ‘Devo Corporate Anthem’ (captured at an Akron gig), interspersed with typical Devo pearls of wisdom… “We’re here to repeat the sad truth that there must be a D placed in front of Evolution”.

Mark Mothersbaugh recounts a peculiar story about the Workforce To The World bootleg, which is so bizarre it trumps even the Branson/Lydon debacle.

“The Workforce record was put out by some people in England,” he says. “You know, what’s funny about it is that one day, two guys turned up at the house I was staying at. They said they’d put out the Workforce bootleg, and they gave me some copies. But they also gave me a medical specimen jar that had a human foetus in it. And it said, ‘Presented to Booji Boy in commemoration of the release of ‘Workforce To The World’.”

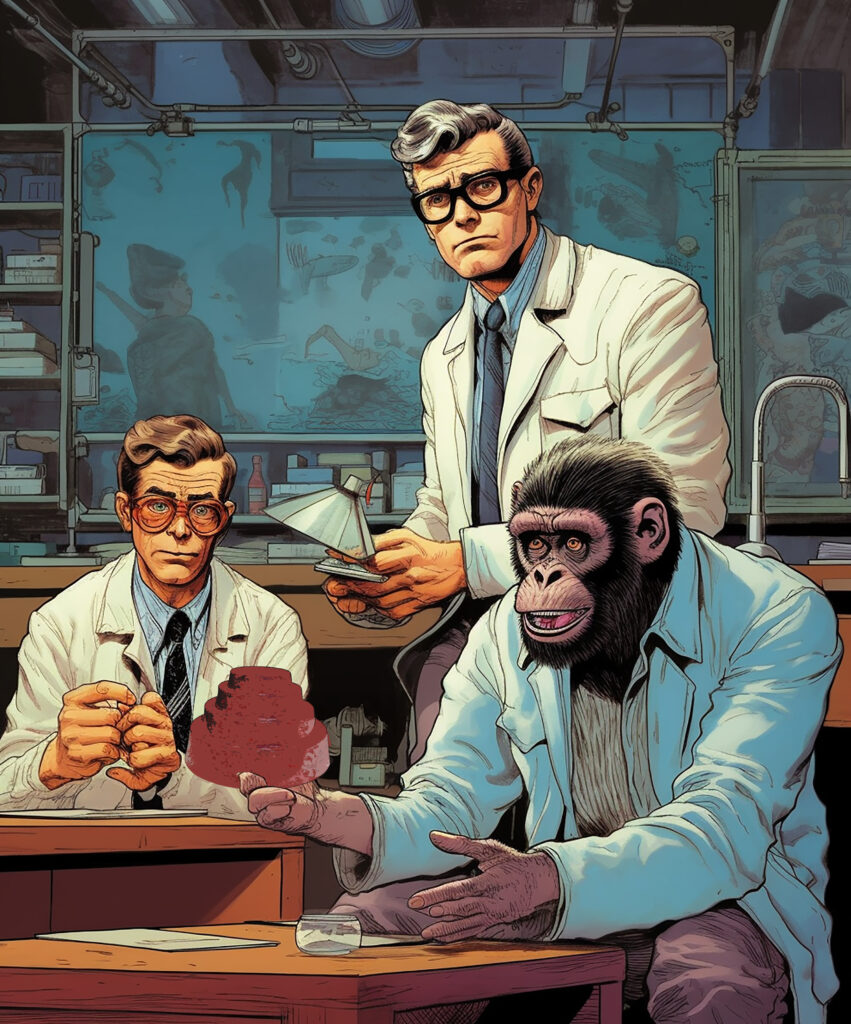

It’s a gruesome anecdote, one that underlines the queasiness with which Devo were often associated when they first emerged onto the world stage. All their talk of mutations, DNA, recombo labs and mankind devolving into apes was more Victorian medical horror spectacle than rock ’n’ roll show… the idea of transgressive films like 1932’s ‘Island Of Lost Souls’ (based on HG Wells’ ‘The Island Of Doctor Moreau’) and ‘Freaks’ – both of which the band were obsessed with – presented by punk scientists dressed in yellow boiler suits.

Devo’s debut album, ‘Q: Are We Not Men? A: We Are Devo!’ was finally released in August 1978. In the UK it was pressed with five different coloured vinyl editions and included two huge posters in the initial run. In America it had a different cover, as did the follow-up, 1979’s ‘Duty Now For The Future’.

Despite its solid collection of songs, including the barnstorming ‘Smart Patrol/Mr DNA’ and equally electrifying new cuts like ‘Wiggly World’ alongside reworks of older ‘Mechanical Man’ faves ‘Blockhead’ and ‘Clockout’ (wrongly listed as ‘Blackout’ on the original bootleg), the second album failed to deliver on the promise of the debut, and Warner Bros delivered an ultimatum. If the third album wasn’t successful, Devo were toast.

Just 18 months after the first album and their spectacular rise to international notoriety, Devo were faced with one last throw of the dice. What they came up with, 1980’s ‘Freedom Of Choice’, was inspired. A synthpop album with fat hit single ‘Whip It’, it reversed the frowns of the record company execs and set up Devo as the band of the 80s, a five-man corporate welcoming committee to the computer decade who toured the world to ecstatic full houses.

That 1980 world tour was the last time Devo would be seen in the UK for a decade. By the time they returned, burned out and exhausted, to promote their 1990 album ‘Smooth Noodle Maps’, they’d released a further five studio albums, two of them with Enigma Records after their contract with Warner Bros ended in 1984.

In the 1990s, it seemed that Devo were finished as grunge became the dominant American musical output. But their flame was carried by both Nirvana, who covered a ‘Freedom Of Choice’-era B-side, ‘Turn Around’, and Soundgarden, who knocked out a version of the 1980 single ‘Girl U Want’ in the early 90s. Devo’s place in the world was secured for the 1990s after all.

They regrouped to play some high-profile Lollapalooza gigs in 1996 and 1997 alongside Metallica, Soundgarden, Orbital and The Prodigy. As Devo’s retro stock rose, they played more and more shows over the next decade, culminating in the unexpected re-signing to Warner Bros for the 2010 release of a new album, ‘Something For Everybody’.

Like many songwriting partnerships in bands, Casale and Mothersbaugh have wrestled with their symbiosis. Unless they’re both working together, there is no Devo. And neither of them wants there to be no Devo in the world. Mothersbaugh has his distinguished post-Devo career as the head of Mutato Muzika, composing music for films and TV, and Casale has various successful projects on the go, including a vineyard and wine company called The 50 By 50, and has released several records under his own name.

But Devo is the defining creative achievement for both of them. This landmark year and the ‘Art Devo’ boxset represents a moment for reflection on their relationship.

“Well, that was when it was wonderful,” says Casale, remembering the 1973-1977 period. “To resonate with each other, be on the same page, meet somebody that you share an aesthetic with, and then the whole becomes more than the sum of its parts and takes off. You play off against each other and the collaboration makes it go far enough. The problem with most creative people is they don’t go for it. It’s like when you think you’ve gone too far, you’re just starting to be on the right track in reality.”

I ask Mark Mothersbaugh how he thinks their creative partnership is holding up after 50 years.

“I think it’s OK,” he says. “We’re going out on shows and we’ve been talking about future records and tours. You know, he’s still one of the most creative people I ever knew in my life. I have to say that about him. And I’m really glad that we collaborated. I think we both really complement each other when things are going right.”

So, far from being the farewell it’s tagged as, the European dates this summer may well usher in a new era of de-evolution.

“Who knows what’s going to happen next?” says Mothersbaugh. “I have maybe 500 boxes of seven-inch tapes with versions of different songs. I think there’s one of ‘Whip It’ – it was called ‘Dump Truck’ or something. It’s got totally different lyrics on it. And there’s all these other tracks that we’ve never pulled out and gone through. We really want to get into it.”

If that isn’t their duty now for the future, I don’t know what is.

The ‘Art Devo 1973-1977’ boxset is released by Futurismo