You join us in Brussels, it’s 1978 and Elvis Costello is in town. His hand-picked support act? Alan Vega and Martin Rev’s Suicide. What could possibly go wrong?

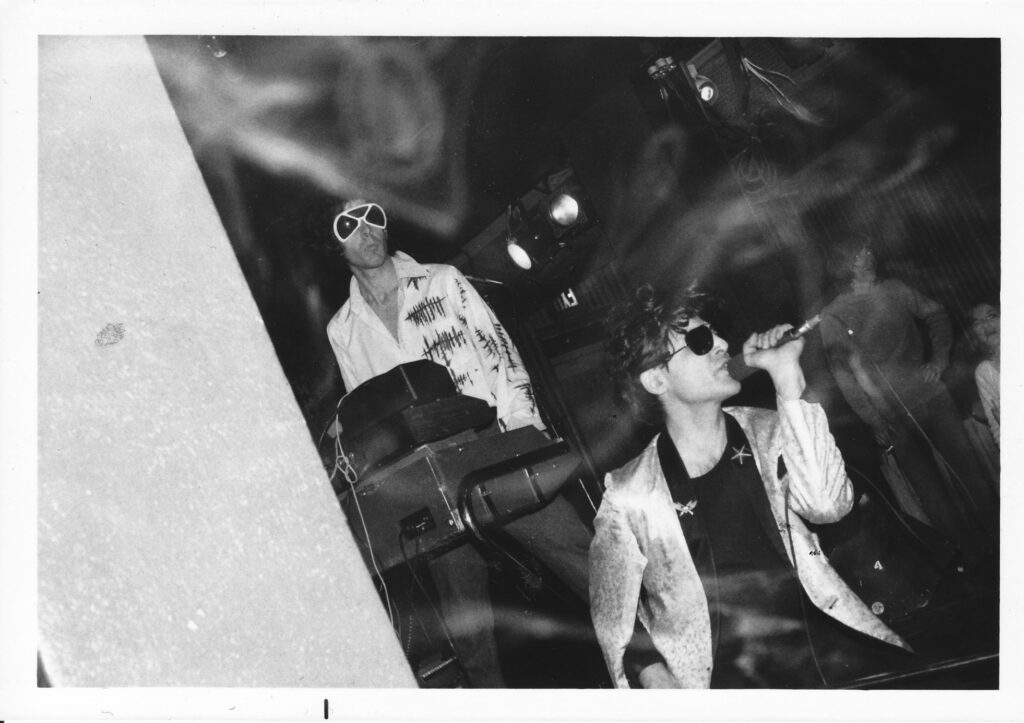

On 16 June 1978, Suicide sauntered onstage at the 2,000-seater Ancienne Belgique Theatre in Brussels. They were supporting Elvis Costello, a huge fan of the New York duo, much like The Clash who Suicide also supported. Self-declared “punks” as far back as 1971 when they advertised themselves as such on their own posters, Suicide had been operative for some 10 years at this point, though they had only released their debut, self-titled album a year earlier.

They were punk before punk, but in minimalist, essentialist terms they went a step further. They were rock ’n’ roll reduced to a voice and machine, with Vega channelling the recently departed spirit of Elvis over the looping, hissing pulses of Rev’s synthesisers.

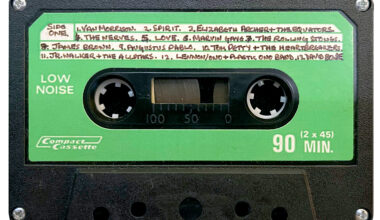

While Elvis Costello was a fan, not all of his audience felt the same way. The gig that night was recorded by promoter Howard Thompson on his Sony cassette recorder – the result, entitled ‘23 Minutes Over Brussels’, would be a lasting artefact of electro-phobic antipathy.

The assembled throng wanted to hear Elvis Costello and his lyrically twisted, acid-tipped but ultimately orthodox rock songs. As Suicide strike up with ‘Ghost Rider’, an initially quiet, grudgingly attentive audience slowly but surely begins to turn restive. This music, thudding, electric, repetitive, didn’t seem to “go” anywhere. Suicide weren’t going anywhere either. And when Vega begins to issue his echo-drenched war whoops, a chorus of lowing boos starts.

Suicide were used to confrontation; Vega practically invited it. Kraftwerk, emerging as another paradigm of an all-electric ensemble were just as provocative in their own way; effete, Teutonic, not-guitar-based, synthetic, short-haired, smartly attired and buttoned up, everything about them was a calculated affront to the honest Anglo-American rock values of sweat, authenticity, fretboard-grappling, hollering, open-necked passion. And yet Kraftwerk, in their serene gentleness, did not incite riots. They were condescended to, treated as comical passing novelties, but they did not excite violent wrath when they played. Rock fans wouldn’t have come near a Kraftwerk gig. Kraftwerk were not rock.

With Suicide it was different. They didn’t reject rock, they were rock in extremis. They played alongside rockers. Suicide were not serene, or amusing. They behaved as if they were on a combat mission, deliberately confronting audiences who thought their heroes were the last word in rock. As they put it to me in 1998, they sought to “widen rock’s vocabulary by getting rid of the guitar and getting rid of the drums”.

While supporting The Ramones at CBGBs, Vega wielded a knife and chain and dared a hostile audience to violence, implying that there was nothing they could do to him that he wouldn’t do to himself. Suicide approached each gig as though they were outnumbered soldiers beamed back from the future to lay a new template.

In Brussels, Rev kicks in with the locked drum machine throb of ‘Rocket USA’. “It’s nineteen hundred and seventy eight.” It inevitably loses some of the cavernous, sonic cinema of the studio version, but even on this bootleg, with Vega unleashing a banshee of overlapping, reverberating volley of apocalyptic horrors, like the wall is fast approaching, it’s unnervingly potent. “Gonna DIE / DIE / DIE / DIE / DIE!”

The Belgian Costello fans, alas, are in no mood to die. They start up a chant, “Elvis! Elvis!”, but, unlike Vega, they aren’t trying to reincarnate the first spirit of rock ’n’ roll. They want Elvis Costello.

“We love you,” counters Vega and urges the crowd to get up and dance to the almost schmalzy, cha-cha tones of ‘Cheree’. They decline, but relapse into a sullen silence. At least the guy’s not shrieking any more. Then there’s half boos, half applause, with Howard Thompson doing his best to whip up some positivity.

Vega tries to bum a cigarette, but it’s a non-smoking venue. Then, “Dance”, a further invocation to the crowd to get up and boogie. Maybe the audience feel messed with, torn from this to the cacophonous, Armageddon hiss of ‘Ghost Rider’ to concede to these banal disco invocations. “Remember we’re all Number One,” shouts Vega.

And then… ‘Frankie Teardrop’, “Someone just like all of you”, which is perhaps the most terrifying foray into the jet-black vortex of synth abstraction ever recorded. Now we’re going to hear something… except we don’t. A big cheer goes up.

We soon learn why. Someone has jumped onstage, taken Vega’s mic and retreated back into the crowd. Vega’s synth still resounds like a static tractor. There’s more “Elvis” chants. Eventually, Vega climbs out of role and pleads for the return of the mic. “We’re just a bunch of poor musicians,” he says. He tries to sing on above the baying of the crowd, a capella, before shrieking, “Shut the fuck up!”.

Unfortunately for the crowd, Elvis Costello is so enraged by the treatment of Suicide that he cuts short his own set. That brings down the real riot, the violence exacerbated rather than quelled by the arrival of police with sticks and tear gas.

Suicide would experience violence when supporting The Clash too, among their more meat-headed followers, including the hurling of a silver axe onstage in Glasgow. And yet, within a few years, the template established by Suicide would by widely emulated – by Soft Cell, by a rejuvenated Sparks, Blancmange, the Pet Shop Boys.

Still, in 1998, despite the ubiquity of electronics, sitting in the lobby of the Columbia Hotel in London, I recall Vega’s expression of dismay as he watched the post-Britpop indie types traipsing in and out, sad, tired evidence of the restoration of guitar rock.

“It’s really strange,” he said, “as we enter the next millennium, computers and electronics are changing everyone’s lives and still they have problems buying into this new music thing. It’s like a fear of going into the next phase. Fear of the next century.”