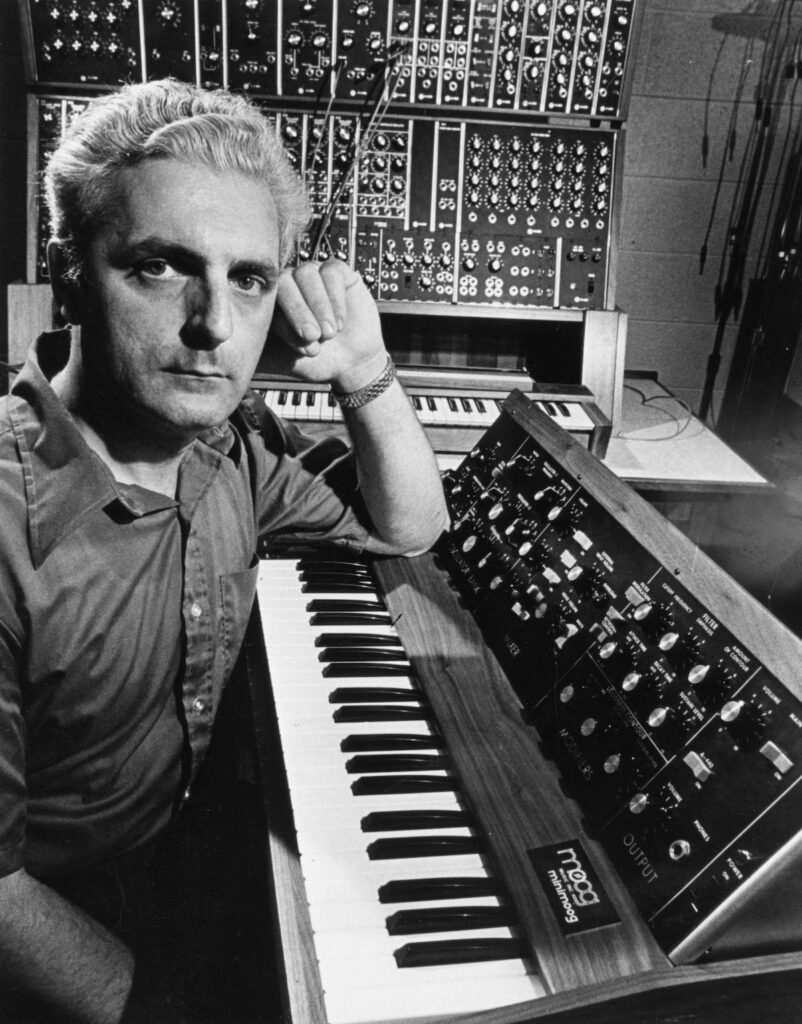

We’re spinning back to 1967, to the birth of Dr Bob’s Amazing Contraption, aka The Minimoog, arguably the most famous synth of all time

If you wanted to take a year out of history and hold it up in order to prove to an alien or a halfwit that pop music contains some of mankind’s finest achievements, 1967 would certainly fit the bill. The Beatles released ‘Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band’, The Rolling Stones released ‘Their Satanic Majesties Request’, Pink Floyd and The Velvet Underground made their album debuts, Jimi Hendrix cranked out two records, and Brian Wilson gave up on The Beach Boys’ ‘Smile’ sessions. So far, so Wikipedia.

The summer of 1967, the Summer of Love, also saw the Monterey Pop Festival, a three-day event held at a county fairground in California. It was a music landmark and is remembered for, among other things, Jimi Hendrix setting fire to his guitar, captured in the ‘Monterey Pop’ movie by DA Pennebaker (who, more than 20 years later, would make Depeche Mode’s ‘101’ film). It’s a nice thought that the iconic torching of a guitar may have a symbolic resonance for fans of electronic music, because Monterey was also the venue for a less flashy but no less auspicious appearance.

You don’t see the names Beaver & Krause in many Monterey Pop write-ups, but they were there. Paul Beaver and Bernie Krause were both well known on the Los Angeles music scene and they set up a booth at the festival to demonstrate the Moog Modular. Dr Robert Moog’s original company – RA Moog Co – was based in New York City at the time, but Beaver was their West Coast rep and his Monterey gamble paid off. This was the year that the Moog was first used on commercial pop recordings, usually played by Beaver. Among the records that featured his Moog sounds were The Monkees’ ‘Pisces, Aquarius, Capricorn & Jones Ltd’, which included the spectacularly bonkers ‘Daily Nightly’, and LA psych-rockers The Electric Flag’s soundtrack to Roger Corman’s film ‘The Trip’.

The following year, Bernie Krause showed the Moog system to George Harrison, who made his album ‘Electronic Sound’ with it (much of it played by Krause himself, although Krause later disowned the release). The Doors’ ‘Strange Days’, issued in late 1967, also boasted Paul Beaver’s Moog contributions, but when he later tried to put the machine through its paces for the band and their producer, recapturing sounds proved very difficult. The modular system, while sophisticated and clearly all kinds of awesome, was unwieldy and just too plain difficult for rock musicians to cope with. Patch cords? On acid? Fuggetabahtit.

Back in New York, the guys at RA Moog Co were by now working on the Minimoog, a machine that would combine an exotic sound palette with something musicians, stoned or otherwise, demanded – playability and portability. The first Minimoog, the Model A, was built by Moog engineer Bill Hemsath from spare parts he found in his workshop during lunch breaks. The keyboard was rescued from what remained of the five-octave keyboard that was being cannibalised for replacement keys. It so happened there were just three octaves left. Where the mod wheel ended up was a blank space, which Hemsath decided needed something, so he put a pot there to bend the note.

After several refinements and unreleased iterations, the final result of a fairly DIY process saw the light of day in 1970 – the monophonic Minimoog Model D. It came housed in a handsome walnut case and the control panel was propped up perpendicular to the three-and-a-half octave keyboard. The control panel could be dropped back into the box for storage and travel. “A Moog for the Road” was the advertising line and the marketing blurb also touted its “affordability”. Which at $1,495, close to $10,000 in today’s money, was stretching it a bit.

“When the Minimoog first came out in 1971 – only one was made in 1970 – it was a slow, tentative start,” says official Moog historian and archivist Brian Kehew. “They had trouble convincing many people of its worth. Some studio and travelling musicians accepted it at first, but it was only a few dozen.”

According to Kehew, it was the tireless efforts of Moog salesman David Van Koevering that made the Minimoog a success.

“He was a touring musician who saw the public response to his own Moog demonstrations. He found that he could move from town to town with a stack of Minimoogs, using clever ideas to convince reluctant music stores to sell the unusual instrument. It’s hard to imagine, but nearly everyone felt a synthesiser was too difficult to understand and operate. Van Koevering showed musicians the sonic power and flexibility of the instrument at their local shows, then he’d take prospective customers to their nearest store to prove to the store owners that there was a market for this odd piece of kit.”

Once prog superstars like Keith Emerson of ELP and Rick Wakeman of Yes started to tour with Minimoogs, its popularity was assured. Before the decade’s end, the instrument had jumped the prog ship as it sank and become the heart of the new wave of electronic music that was building momentum. Kraftwerk were very early adopters of the Minimoog – it’s all over their breakthrough 1974 album ‘Autobahn’ – and when Gary Numan discovered one in the studio while trying to record ‘Replicas’, the follow-up to his ‘Tubeway Army’ debut, he used it to rewrite most of the album. Giorgio Moroder remodelled R&B with a Minimoog and gave the world disco, while jazz virtuosi like Herbie Hancock and Chick Corea were able to play dazzling solos on them. Even Bob Marley made use of the Minimoog.

There were other synthesisers out there, notably ARP in the USA and EMS in the UK, but the Minimoog is electronic music’s Hoover – a brand name that, for many people, may as well be what every synthesiser is actually called.

“The Minimoog became the cornerstone of the Moog company,” says Kehew. “Most later instruments were based upon the classic Minimoog set-up, a tradition that continues today.”

“The Minimoog Model D was the launchpad that propelled the company into studios, onto stages and into stores all over the world,” says Mike Adams, the President and CEO of Moog Music. “It also single-handedly transformed the sound of popular music and its system architecture is still the foundation of all Moog instruments that have followed. It is the legacy that we stand on and we work hard to preserve and advance that legacy every day.”

If you want to buy an original Model D, they fetch around £3,500 these days. For a similar wad you can get a brand spanking new Minimoog Voyager, designed by Dr Robert Moog himself, which won’t detune or get upset if you look at it in a funny way, unlike many of its vintage predecessors. The choice, as they say, is yours.

For more Moog history, visit moogseum.org