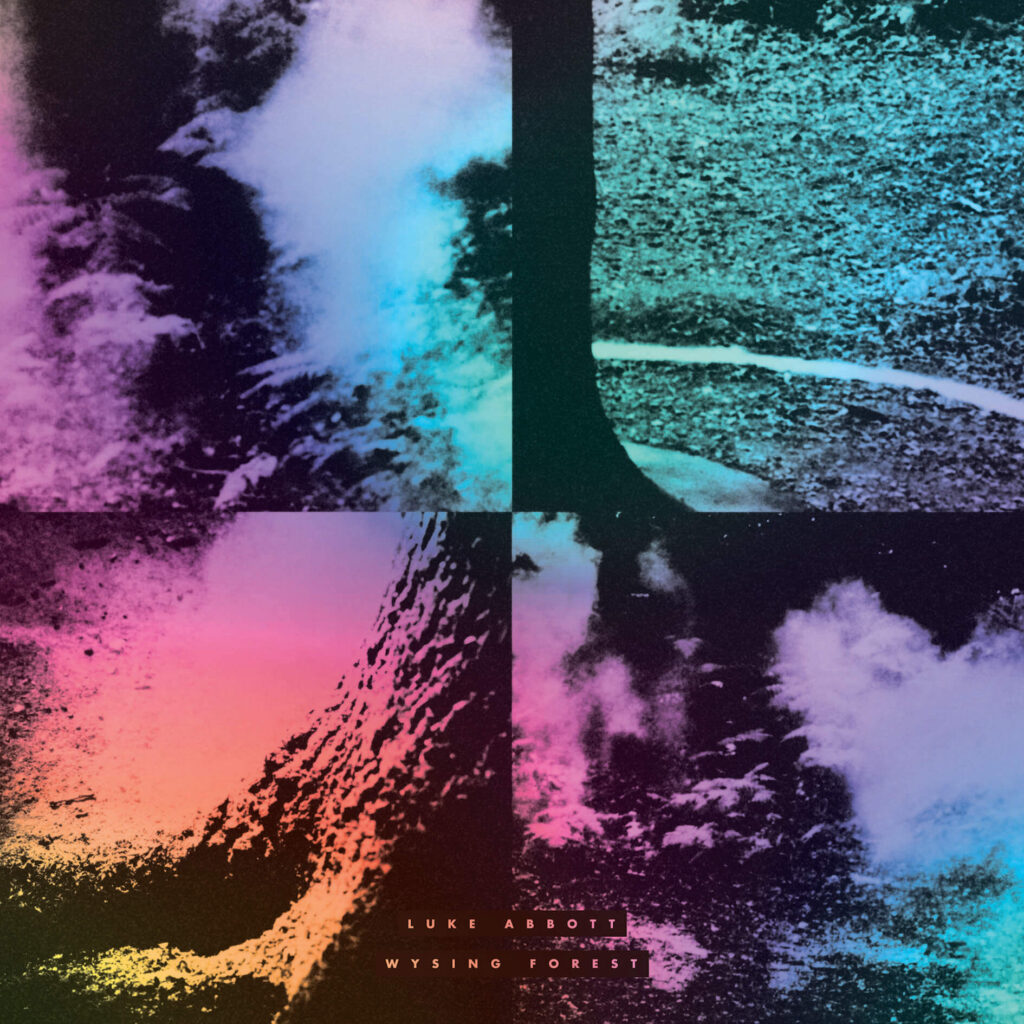

Rural art project involving modular synthesis awash with strange and beautiful sounds and melodies

A slow wave of sound emerges; clear tones overlapping to create a wash of soothing melodious electronics, like Eno might have done once upon a time, back when the sharpest of the cutting edge of musical tech was modular analogue synthesis, long before he went digital (or started using that hand wavy thing he’s been spotted manipulating in the company of Karl Hyde). And then an insistent thumping starts up. It’s warm, but it’s urgent and there’s a tension in it. As the tones continue, they start to become swamped by white noise. It sounds like the huffing and puffing of a stationary steam train. Other noises spring out of this; slightly detuned notes ring out in some kind of damaged trumpet voluntary, woozy yet victorious.

Then that rabbit’s heartbeat of a pulse comes back in, slows, takes up a tempo and a feel reminiscent of Pink Floyd’s ‘Time’ from ‘Dark Side Of The Moon’, and the swaying melodic theme swirls back into focus.

Then you realise that two tracks have come and gone (‘Two Degrees’ and ‘Amphis’) and 15 minutes have passed as the third piece, ‘Unfurling’, kicks off. ‘Unfurling’ sounds more like the kind of experimentation Steve Reich liked to play around with, where he’d set off a couple of tape loops and record the results as they slipped out of synch and then back in again, drawing more meaning from the accidental coinciding of tones and the creation of unintended rhythmical elements than from the original loop itself.

Luke Abbott’s own modus operandi here certainly owes more to the academic minimalists and electronic music pioneers than it does to the commercially successful creators of electronic pop music or dance music. With the blessing of the Arts Council (and, you have to assume, some cash), Abbott hauled himself off for a week or so to Wysing Art Centre in Cambridgeshire, where he installed himself and his modular sound-making kit in a white room. This album is the result.

Interesting, this intersection of art and electronic music. So should we expect some kind of rural concept album from this exercise, you know, like a ‘Campfire Tapes’ of the Nintendo generation? That would be literal to the point of stupidity. What we have with ‘Wysing Forest’ is a recording of what happens when several ideas and circumstances collide; a musician who thinks like an artist, a place that isn’t his usual recording studio, and the absence of commercial considerations (like shifting units, remixes for the dubstep crowd, etc).

Despite the lofty art concepts at work here, Abbott’s not above pulling the Jean Michel Jarre laser guns out of his arsenal (‘Free Migration’) and nor do they preclude the use of very pretty melodies, something which he keeps being drawn to, whether he wants to or not. In the end, this is why Luke Abbott’s work is so appealing; unexpected tunes taking flight from a canvas of sound created through a number of fascinating creative decisions. Not least of these is his decision to use modular equipment that is, with a time travelling irony that may yet see Eno get into it again, once more at the cutting edge of electronic music making.