Gold Blend

You might think I’m being satirical for laughs here, but have you been to the paint section of B&Q lately? Only, I have, and I came away with 2.5 litres of Wispy White with which to redecorate the downstairs toilet. So far, so mundane. But part of the very great pleasure of choosing that paint was the spectacle of the paint chip display. Hundreds, maybe thousands, of colours, all arranged according to their hues and tones in a bespoke shelving system that stretched for three or four metres, filling your field of view. It’s dazzling. And then there are the names. Wispy White is among the more mundane. Gilded Age is a deep Colman’s mustard yellow, there’s a purple called Deep Ocean Floor, and Tempest’s Teapot is a particularly lovely dark grey.

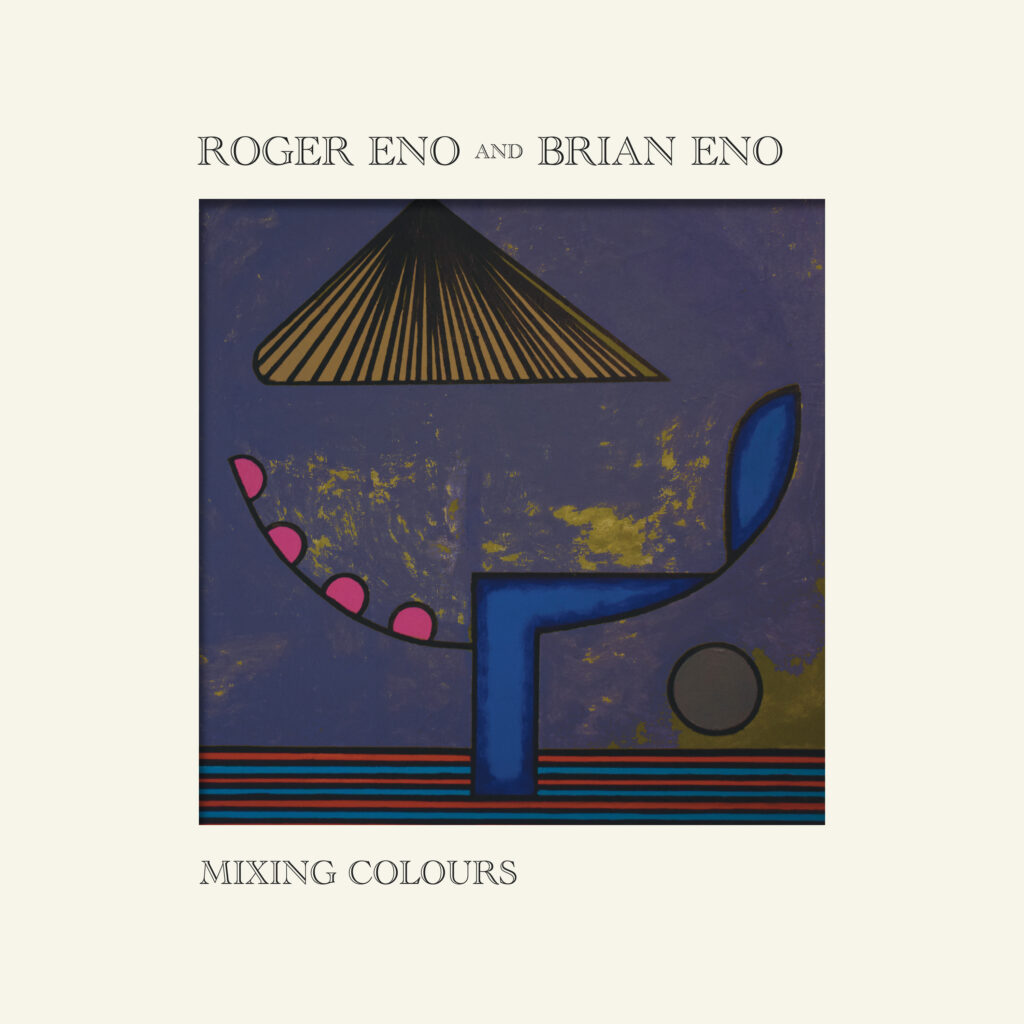

Roger and Brian’s colour mixes on this beautiful album are less fanciful, and more authentic, based as they are on pigments and colours observed in nature: track titles include ‘Verdigris’, ‘Cerulean Blue’, ‘Burnt Umber’ – these are abiding light-fast colours created when copper is exposed to acetic acid, or from cobalt, or from iron oxide from the earth. ‘Obsidian’ (black) has swirls of celestial clouds moving slowly across the sound field, a mutated organ flow with emphasis on the tingling of the upper resonances, with all its hints of the sacred intact, glistening like the polished volcanic glass it’s named after.

The word “mixing” here is on double duty, of course. It refers to the colours themselves and how the tone colours created by the piano are melded into electronic tones, with Eno Snr subtly blending his younger brother’s understated and restrained playing into the wider landscape of the album.

The image of the brothers Eno at the paint counter of their nearest Suffolk DIY shed, watching their tins vibrate in the mixing machine, probably isn’t quite what they were aiming for. But the quotidian nature of B&Q paint is, I’d argue, the point. Yes, we associate the Eno name with art school, Brian is the consummate British art school graduate, but he didn’t get that involved with paint on canvas. He was more your video/sound/concept type. But the environmental nature of colour – “Blue blue electric blue, is the colour of my room” as Bowie sang on ’Sound And Vision’ on that first Berlin album he made with Eno – that’s where Brian Eno’s thoughts have so often turned. His music has always been addressing the environment, the space we occupy, and how music alters our perception of those spaces.

The music on this beautiful album was produced by Roger playing the pieces and sending the resulting MIDI files to Brian, who would then install them on his system and manipulate them, with a very light touch by the sounds of it. It is, then, essentially a piano album. The looming influence of Erik Satie is unmistakable, in the graceful hesitancy and the slightly jarring intervals here and there, as is the gentle and quiet romance of Schubert. There’s a hint of Vladimir Cosma’s ‘Promenade Sentimentale’ (on ‘Blonde’). Roger’s playing, as ever, is sensitive and tender.

Sonically, Brian is still exploring the possibilities of subliminal electronics. ‘Rose Quartz’ gently echoes with the bell-like piano, and it lurks in the background of more acoustic piano dominated pieces like ‘Celeste’ (sky blue, favoured by the Italian bicycle manufacturer Bianchi).

Technically, the use of MIDI files to create this album is a very simple process in 2020, but it would have seemed like the most outlandish magical science fiction to the likes of Satie and Schubert. Somehow with ‘Mixing Colours’ the sheer wonder of the power of technology and data manipulation to create beauty is rendered astonishing all over again. We are not much wowed by technology in the age of AI and Instagram filters that replicate ‘Terminator’ liquid metal effects in real time, but imagine all that human touch communicated over MIDI files, your brother’s every stroke of the keyboard contained in data, reassembled in a studio, where if you closed your eyes you would think he was playing in the same room. If MIDI had existed when Satie or Schubert was alive, we would have an archive of their playing technique. Soul-capturing stuff.

I wonder what the deal with Deutsche Grammophon looks like? Is it a one-off? I sincerely hope not. Because, a bit like that can of Wispy White I bought, one is not enough.